If Ansarallah controls Marib, it will control all of Yemen and some of the world’s most strategic waterways. No wonder its adversaries are shaken.

By Karim Shami

Marib, the ancient capital of Sheba, referred to in both the Bible and the Holy Quran as a wealthy and wise kingdom, once ruled across the entire southern Arabian peninsula.

Today, Marib has risen again, this time as the final stronghold of Yemen’s latest invaders, now in panicked retreat after a six-year battle that has depleted their coffers and exhausted their forces.

This war was announced from Washington on 26 March 2015 and led by Saudi Arabia in support of the overthrown government of Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, a regime that had already lost the capital city of Sanaa to Yemen’s Ansarallah (Houthis) movement a few months prior.

A coalition of 10 countries, including pack leaders Saudi Arabia and the UAE, was formed to force the return of his highly unpopular government. The name Operation Decisive Storm was chosen and the air strikes began.

Ansarallah were assessed as being weak and the operation was expected to last no more than a few weeks or months, at the most.

Instead, Ansarallah prevailed, forcing its Saudi and Emirati foes to insert ground troops into the expanding quagmire and divide their roles in Yemen.

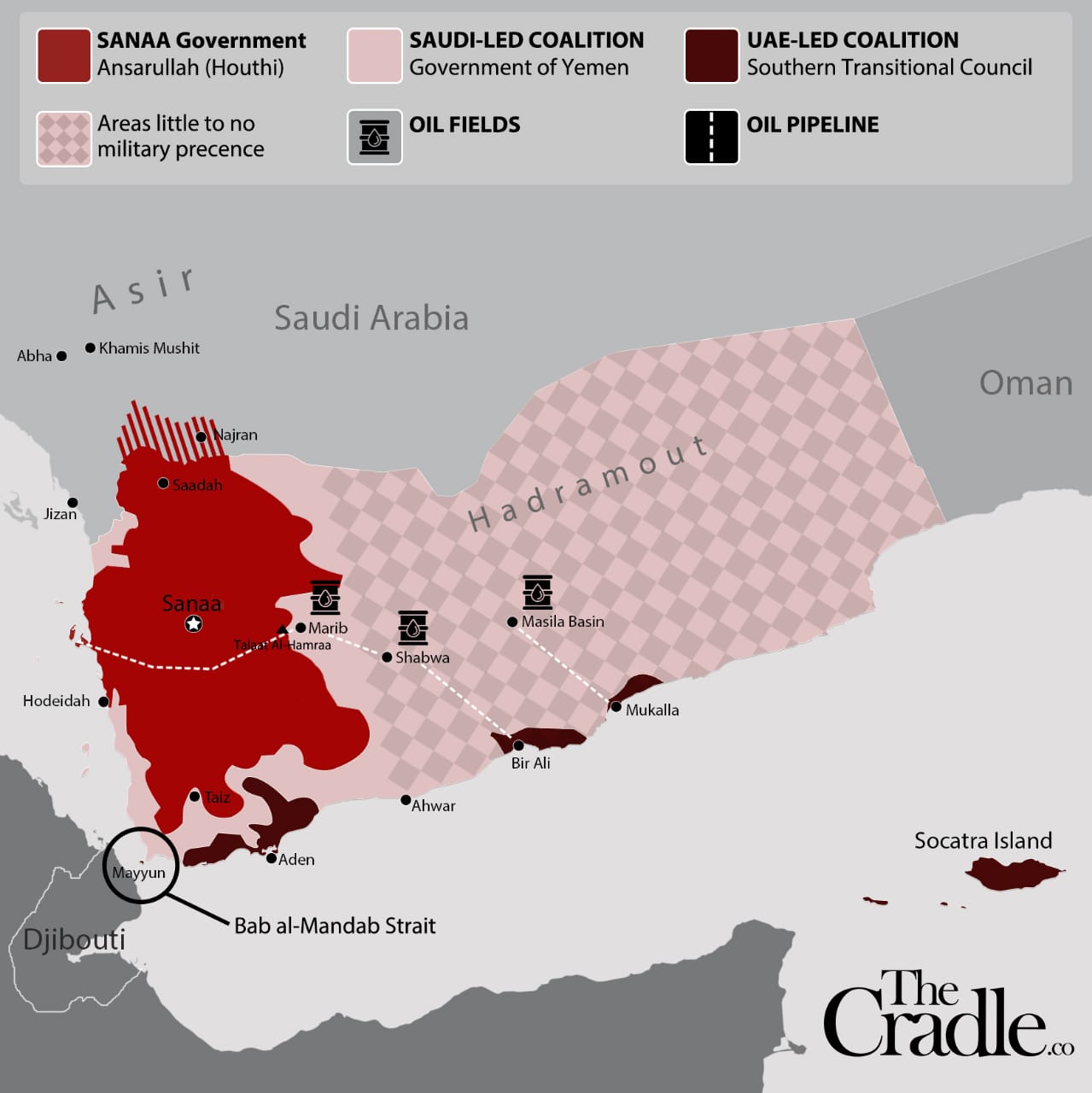

Today, the UAE is present mainly in the country’s south controlling its strategic ports and islands, while the Saudis remain in the north, along their extensive northern border with Yemen, in the east, where the province of Marib and its rich oil and gas fields are located, and in the west, in the coastal city of Hodeidah.

For Yemenis, the importance of Marib is not limited to its oil and gas fields, but also for its ancient culture, its inclusion in the holy Quran, and its significant historical sites and water engineering feats, such as the ancient Marib dam built around the 8th century BC. A new dam, the country’s largest, was later built near the cherished ruins of the old one.

Saudi Arabia acknowledged Marib’s importance by making it the stronghold for its war operations, building military bases and bribing local tribes to fight alongside the coalition. Most of Riyadh’s military and intelligence operations – excluding air strikes – were launched from Marib against the northern Houthi-controlled Sanaa city and province.

Ansarallah endured these onslaughts for three years, then flipped the war on its adversaries in 2018 by going on the offensive. Since then, the group has expanded its territorial gains significantly, destabilized Saudi Arabia’s own borders, and exponentially advanced its military tactics and capabilities in drone and missile technology.

These startling gains forced the coalition to the negotiating table in 2018 to sign the Hodeidah Agreement. The agreement was a boon for Ansarallah from a military perspective, first and foremost. Hodeidah and its Red Sea port are west of Sanaa, and the negotiated ceasefire would help Ansarallah turn its focus on only two fronts now, the east (Marib) and the south.

But the agreement also had humanitarian benefits for a country besieged by land, sea, and air by coalition forces since the war’s onset. With goods now entering the port, fresh access to medicine, fuel and food reduced the crisis in territories controlled by Ansarallah.

In 2019, Ansarallah marched eastward, increasing their defence operations inside Saudi Arabia, and targeting the capital city of Riyadh, airports, and Aramco facilities in retaliation for Saudi airstrikes. The UAE was also threatened when drone activity caused a brief closure of Dubai airport.

The UAE’s very existence depends on the security of Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Understanding that they were one ballistic missile away from an existential disaster, the Emiratis withdrew from Marib leaving the Saudis to their own devices, and headed south. The ten-nation coalition had now dwindled to two, neither of whom were fighting alongside the other.

For Sanaa, access to oil is a higher priority than access to ports, hence Ansarallah’s decision to first push eastward, where Marib lies. Although the reverse would have been easier – at 17,000 km², Marib requires a huge military presence, while Hodeidah port and its surrounding areas are less than 1,000 km² – the Yemeni rebels chose the harder, more dangerous fight first.

Today, the complete liberation of Marib is imminent. Of its 14 districts, 13 are now back in Yemeni hands, with only Marib city and the oil fields remaining, alongside one major Saudi military base (Sahen Jin).

Marib’s liberation will be an unprecedented victory for Ansarallah that will place Sanaa back firmly on the world map. Aside from the huge morale boost for the Houthi rebels, Ansarallah will gain control of Yemen’s vital water and oil resources and bring relief for the capital’s civilians. Despite the fact that areas controlled by the group enjoy more financial stability ($1 = 600 Yemeni Rials versus 1,480 Rials in areas outside their control) the war has impoverished Sanaa.

Marib’s liberation will also mean that Ansarallah will govern around 80 percent of the Yemeni population of 30 million, secure its eastern front, and make a move on Hodeidah where remaining coalition forces are based.

After the liberation of Hodeidah and Marib, Saudi Arabia will lose its boots on the ground in Yemen, but will it retreat and accept defeat?

Will Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman – also his country’s minister of defense – who spearheaded the war against Yemen, accept this fait accompli? Will Saudi Arabia continue bombing Yemen for another six years?

With so many unexpected victories under its belt, Ansarallah is now in a position to direct these Saudi decisions. Already this year, the Yemeni rebels have bombed Aramco and Saudi airports in retaliation for airstrikes in Sanaa. Riyadh clearly understands the correlation – bombing Sanaa means Aramco will get hit – and so although the war is still fiercely being played out, important deterrences have been established.

In September, during the approach toward Marib, Ansarallah leader Abdul-Malik al-Houthi said: “We will liberate the entirety of our country and recover all regions occupied by the Saudi-led aggression.”

After the fall of Marib, Saudi Arabia will never be the same. Having expended all its chips and a vast fortune on bringing the Houthis to heel, Riyadh’s influence in the Arab and Muslim world are set to decline.

Through proxies and large financial donations, the Saudis have historically managed Muslim communities and dictated the policies of entire states. But in an actual direct war, led by one of the world’s wealthiest nations against one of its poorest, the Saudis lost resoundingly.

After the fall of Marib, the UAE’s position is less clear, but it will ultimately face one of two choices: either surrender to Ansarallah’s demands or face reprisals inside Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Yemen has vast mineral reserves of zinc, silver, nickel, gold, copper and cobalt as well as oil and gas fields, resources that the Saudis have not allowed successive Yemeni rulers to exploit, develop or monetize since 1934.

Yemen was then (arguably still is) considered a Saudi backwater, and Riyadh’s policy toward its southern neighbor was entirely driven by the kingdom’s founder, Abdul Aziz Al Saud, who declared in an infamous quote:

“the honor of Saudis is in the humiliation of Yemen, and their (Saudi) humiliation is in the glory of Yemen.”

These words had monumental significance: the guiding principle for all future Saudi monarchs would be to subjugate Yemen at all cost, or the price would be existential.

With Ansarallah in charge, reverberations will be felt across West Asia – not least because Yemenis still consider the Saudi provinces of Jizan and Najran to be part of Yemen.

Yemen is often referred to as the ‘birthplace of Arabs,’ with numerous tribes stretching across the Arabian peninsula to Iraq tracing their origins back to Yemen.

At the other end of the Arabian peninsula, Ansarallah will also be controlling the strait of Bab al Mandab which leads directly to the straits of Suez. This gives them geopolitical and geoeconomic clout over Egypt, historically the ‘mother’ of the Arab world, and a country which itself has launched a failed war against Yemen.

Ansarallah controlling access to the Suez Canal will be a nightmare for the Israelis – Tel Aviv and Zionism are the mortal enemy of the Houthis, and no ship heading for Israel will be allowed to cross this strait.

China and Iran will be big winners in the ensuing geopolitical shuffle. Iran will gain its first diehard ally in the Arabian Peninsula – one that has oil, produces its own weapons, and can defend itself without costing Tehran money, manpower or resources.

Yemen’s geography is of strategic importance to China too: its southwestern part faces the east coast of Africa, and with the Bab al Mandab strait, Yemen has more than 10 major ports on the Indian ocean, and through the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

It is the closest West Asian nation to the Horn of Africa, where China has its only overseas military base in Djibouti, and where it has built roads and railways connecting the latter to Ethiopia.

With the US, UK and western countries in general having supported the aggression against the Yemeni people, Ansarallah is more likely to choose to align with China, Iran, and other unaligned nations.

Reports indicate that Saudi Arabia spent well over $300 billion on its war on Yemen. Six years later, it is on the verge of being soundly defeated, with only Marib blocking that path. Marib is the city that will soon dictate the terms that end this war, and perhaps the end of Saudi power projection as we know it.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of The Cradle.Author

Filed under: China, House of Saud, UAE, Yemen | Tagged: Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, Ansarullah, Bab al – Mandab, Hudaydah, Marib, MBS, Saudi-led war on Yemen, Siege on Yemen, Suez Canal, West Asia |

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 25th, 2021

November 25th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: