After my parents passed away, I began to look through a pile of photos showing them when they were refugees in Germany after the Holocaust. The photos are puzzling: My parents’ families have been murdered in Poland by the Germans, dark clouds hang over the future, and yet they look like they are on vacation. They are smiling, lounging in bathing suits, and drinking beer in cafes.

Together with other descendants of survivors, I have been trying to figure out what was going on during this period our parents seldom mentioned.

Between 1946 and 1949 about 250,000 survivors took refuge in American-occupied Germany. Fleeing anti-Semitism and Communism, they hoped the Displaced Persons (DP) camps set up by the American Army would serve as a gateway to the emerging Jewish state or to the West.

As the British blocked their entry to the nascent Jewish homeland and the United States, Canada and other countries refused to let them in, a long waiting period ensued. Bolstered by food and clothing from American Jewish relief organizations, the DPs soon launched a huge baby boom.

Seven decades later, these “babies” are connecting with one another through Facebook groups and reunions — even though most of them last saw each other while lying in a baby carriage.

The Bad Reichenhall DP camp, circa 1947. (Courtesy of Leah Rochelle Ilutowicz Zylbercwajg)

One thing many of us have in common, oddly enough, is an inheritance of large numbers photos from the DP era, left behind by our parents, whose stories about the Holocaust tended to overshadow reminiscences of the period that followed.

In the last few years the children of Jewish DPs who lived in Bad Reichenhall, Feldafing, Eichstatt, Foehrenwald, St. Ottilien and other Bavarian towns have either met up in Germany or via the internet in order to piece together what life was like during that time.

They finally had the opportunity to have a good time and dammit if they weren’t going to do it

Many of the photos handed down to other descendants convey the same carefree atmosphere that mine do. At the St. Ottilien meeting one participant even quoted his parents as describing those days as the happiest of their lives.

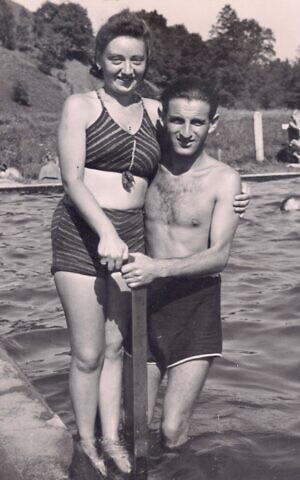

Regina and Joseph Dichek swimming at the Bad Reichenhall, Germany, displaced persons camp after the Holocaust. (Courtesy Bernard Dichek)

“They were young people who now had a secure place to stay,” said Burt Rochelson, an American physician whose father reached St. Ottilien along with a group of Lithuanian Jews who escaped from a bombed train. “They didn’t dwell on the past. They were human. They finally had the opportunity to have a good time and dammit if they weren’t going to do it.”

The desire to not look back was a sentiment that Abe Mazliach recalls his father expressing about his time at Feldafing.

“When my father was on his way to Feldafing, an American army officer told him to try to forget the past and start a new life,” says Mazliach. “That’s what Feldafing became for him and that’s why you can see many happy moments in those photos.”

Mazliach, an American computer expert, notes that one of the exciting aspects of sharing photos has been discovering his parents in photos provided by other descendants.

“Years after he passed away I suddenly saw my father pictured in a music band at Feldafing with fellow Greek survivors from Thessaloniki,” he says.

Newlyweds Lola and Leon Mazliach, sitting in the center. (Courtesy Abe Mazliach)

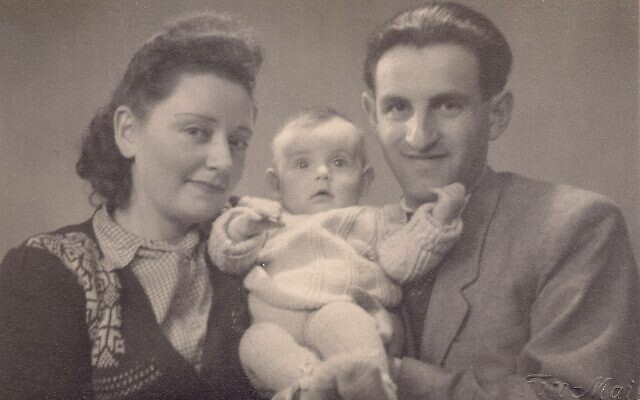

As numerous marriages and childbirths took place, many photos document those events. Indeed one of the few photos I remember my parents displaying shows them proudly holding in their arms my newly-born sister Dina.

Yet it is the anguish associated with these joyous moments, that were the moments most often recalled in later years.

Regina and Joseph Dichek with their baby daughter Dina. (Courtesy Bernard Dichek)

“In almost every story I heard about a DP wedding, someone would say how they remembered a sad moment when they realized their mother and father weren’t there,” says Atina Grossmann, a historian who notes that it may have been awkward for the survivors to speak about that period later on.

It was blood-soaked earth, but it was defeated earth

“It was an ambivalent time for them. They were able to jump into a lake and swim in the perversely beautiful German landscape. It was blood-soaked earth, but it was defeated earth,” she says.

Grossmann makes a distinction between the type of photos that appear in public archives and the private photos that the survivors had taken of themselves. She explains that the former, which are the ones most often used to teach the history of the DP era were usually taken by fundraising organizations such as the American Jewish Joint Development Committee.

Historian Atina Grossmann. (Bernard Dichek)

“The JDC wanted to show surviving Jews as hardworking in workshops as auto mechanics or sewing or learning agriculture. They didn’t want to show young couples flirting in the mountains,” Grossmann says.

She hypothesizes that photos like those of my parents were likely intended as mementos, though they may have had another purpose. “They may have been trying to send a message to distant relatives that they were young and strong and not traumatized — even if they were,” Grossmann says.

In the case of my parents, the photos were sent to relatives in Toronto and New York who were trying to arrange their immigration to Canada or the United States.

Letters accompanying those photos sent by my father make it clear that he and my mother did not want to be seen as a burden. The number of times his letters repeat that claim lead me to believe that those relatives may have required some convincing.

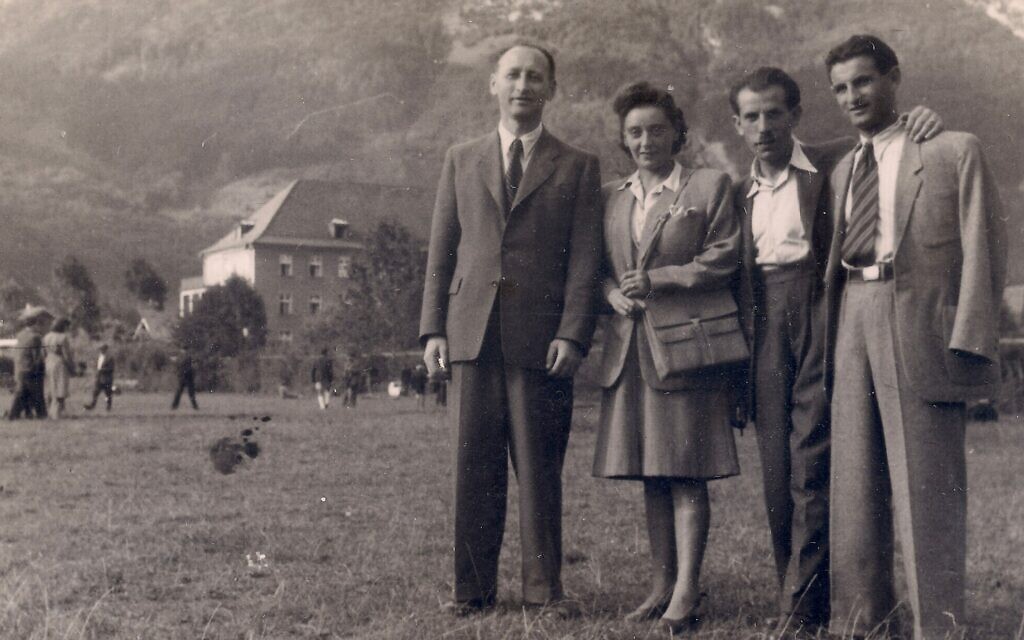

Regina (center) and Joseph Dichek (at right), with the Bad Reichenhall displaced persons camp in the background, Germany, circa 1946-1949. The clothing may not have fit well, but it was well-made and clean, and in most photos Regina and Joseph Dichek are seen wearing different outfits, thanks to the generous donations of the JDC and other relief organizations. (Courtesy Bernard Dichek)

“It may have been easier for North American Jews to donate money than to welcome the survivors into their homes,” suggests Israeli historian Tom Segev when I asked him if the North American Jewish community may have echoed the negative attitude towards the survivors among Israel’s pre-state leaders that Segev has written extensively about.

“The Jewish Agency leaders, starting with [David] Ben-Gurion, were afraid of what the survivors were like. They were suspicious of how they had managed to survive,” says Segev, who noted in his book “The Seventh Million” that an envoy sent to the DP camps claimed that the arrival of the survivors would turn the Jewish state into “one big madhouse.”

“Many people simply didn’t want to live in a building with people who had concentration camp numbers on their arms,” adds Segev.

Many people simply didn’t want to live in a building with people who had concentration camp numbers on their arms

Regardless of whatever feelings the pre-state leaders may have had, Segev emphasizes, the policy they put into place the day Israel became independent was very clear. “As of May 15, 1948, Israel became the only country on earth that was willing to accept all of the survivors, regardless of their condition,” Segev says.

I continued to try to understand why the DP period was often neglected while on a trip to Germany, where I visited the places my parents stayed in Bad Reichenhall. I soon discovered that the Jewish DPs were not the only ones who seldom spoke about that era.

“They were difficult times when we were grateful if an American soldier would give us a banana,” recalled an elderly man at a German military cemetery. Decked out in traditional Bavarian costume with a feather in his cap, he pointed out that unlike the Jewish refugees, no one supplied the Germans with food at a time when food was scarce.

More than 400 Jewish DPs gave birth at the St. Ottilien Monastery hospital in the late 1940s. The monastery also provided housing for many DPs. A conference attended by more than 20 babies born there took place in June 2018. (Bernard Dichek)

As Grossmann points out in her book “Jews, Germans and Allies,” the only jobs available for many Germans was working in the DP camps, where the tasks were often quite menial. I could not help but notice a great irony of history: Only a few years after German leaders had described the Jews as vermin, many Germans found themselves washing the clothes of Jews and scrubbing their toilets.

Despite the shame many Germans may have felt about those days, some of their descendants have found it important to reflect on that period. Last May the town of Feldafing planned a memorial event to commemorate 75 years since the founding of the DP camp.

“It was difficult to get local support as people are very reluctant to talk about those days, but in the end we succeeded,” says Claudia Sack, a German sculptor whose father was employed in the Feldafing DP camp and who, along with the local mayor, helped plan the event. “Unfortunately, the coronavirus crisis made us cancel the event, which was to include a delegation of former Feldafing DPs from abroad.”

An exhibit of photos of babies born to Jewish displaced persons at St. Ottilien. (Bernard Dichek)

Finally, one other reason why the DP phenomenon has often faded into the background seems to be related to the relatively late stage in the lives of the survivors when the rest of the world started to take an interest in them.

During the 1950s and ’60s, those survivors who did talk about their experiences usually only found listening ears in their families or limited Jewish circles. This was certainly the case for my parents and their survivor friends in Canada, where they lived after immigrating there in 1949.

The turning point was the American TV series “Holocaust” in the ’70s, which along with Claude Lanzmann’s film “Shoah” in the ’80s and Steven Spielberg’s film “Schindler’s List” in the ’90s, were all milestones that put the Holocaust on the world map. New awareness culminated in 2005 with the United Nations declaring an annual International Holocaust Remembrance Day. It was only then, decades after the Holocaust, that schools began to seek out survivors as speakers and communities started to build Holocaust memorials and museums around the world.

Regina and Joseph Dichek, at right, attend a wedding. (Courtesy Bernard Dichek)

Consequently, when the day of recognition for the survivors did come, it was the stories of the Holocaust that people wanted to hear. The days of the DP camps were seldom asked about, and the topsy-turvy events of a period when the tables were turned on victims and perpetrators didn’t fit the narrative of the genocide.

As I look once again at the photos, even after all the explanations and speculations, in some ways the truth of what those days were really like continues to elude me. Yet, as Mazliach pointed out: “Now that our parents are no longer here to tell their stories, it’s up to our generation to pass on whatever we can.”

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 28th, 2021

January 28th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: