When the flight crew for the latest SpaceX mission took off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on Thursday, November 11, German-born astronaut Matthias Maurer was carrying a replica of one of Germany’s most well-known archaeological artifacts with him. You could say this historic flight was really the “Nebra Sky disk spaceflight.” A replica of the ancient Nebra Sky disk, the oldest portable map of the night sky ever to be found, was taken on the flight by Mr. Maurer. Moreover, the real artifact will figure in a major Stonehenge at the British Museum beginning in February 2022.

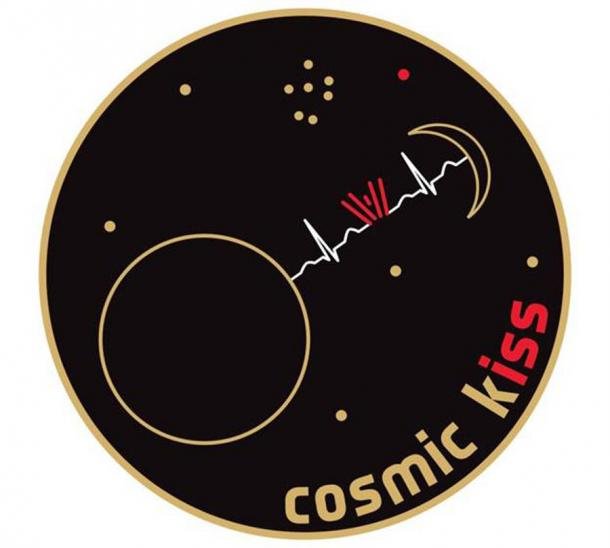

Maurer, as a representative of the European Space Agency (ESA), was joined by three NASA astronauts on the Nebra Sky disk spaceflight, which was headed for the International Space Station. Maurer has self-titled the 6-month space project as the “Cosmic Kiss” mission, which has its own logo label based on the Nebra Sky disk.

At various times during the Cosmic Kiss mission, Mr. Maurer will also host televised educational events that will explain the meaning and significance of the Nebra Sky disk, which was unearthed in 1999 by illicit artifact hunters exploring near the village of Nebra in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. The disk was unearthed during an illegal excavation of multiple Bronze Age objects from 1600 BC, all of which were eventually recovered by German authorities.

The Nebra Sky disk spaceflight has been dubbed the Cosmic Kiss mission by German-born astronaut Matthias Maurer and the logo is based on the ancient disk. ( ESA)

From Discovery to the Nebra Sky Disk Spaceflight

UNESCO, which has included the Nebra Sky disk on its “Memory of the World” registry, refers to the ancient sky map as “one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th century.”

The circular-shaped disk or plate was made from bronze and weighs in at a hefty five pounds (2.2 kilograms). It has a glossy blue-green finish and is inlaid with pieces of gold shaped into figures recognizable to anyone who has ever gazed at the night sky.

It can often take months or years for archaeologists to decode the mysterious markings or images that appear on recovered ancient objects. But they’ve had no such problem figuring out the meaning of the visual display contained on the face of the Nebra Sky disk.

This remarkably well-preserved 12-inch (30-centimeter) sky map features clear and unmistakable representations of the sun and the moon and many stars. Among the latter are a cluster that seems to be the Pleiades constellation, which plays a prominent role in the mythological traditions of the ancient Greeks and Australian aborigines .

The disk also features golden markings that are believed to represent the summer and winter solstices. This helps reveal the object’s likely use as a combination star map and calendar. The solstices mark the clear separation of the seasons, and as such would have been important markers for Bronze Age agricultural peoples who needed to know the right time to plant their crops each year.

In its shape and design, the disk bears an obvious resemblance to many of the Neolithic and Bronze Age earthworks and megaliths that were built to track the movements of the sun and other astronomical phenomena. The disk could very well have represented a portable version of monumental structures like Stonehenge, made for those who wouldn’t have access to the real thing. It might have been modeled after an actual Bronze Age megalithic monument site in Germany that has yet to be discovered.

There has been some controversy over the dating of the Nebra Sky disk. In 2020, archaeologists from Goethe University Frankfurt and Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich who’d studied the disk declared it was an Iron Age artifact that had been manufactured 1,000 years later than previously believed.

At least for now, however, the experts who’ve studied the disk most closely are sticking with their original conclusion, that it is an authentic Bronze Age relic and the oldest representation of the night sky ever found.

Replica of the find situation of the Nebra Sky Disk for the major German museum exhibition “The forged sky” in 2004. (Christian Reinboth / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

The Ancient Únětice Culture’s European Trade Networks

The Nebra Sky disk was found buried in a region of central Germany, which links it to the Únětice culture that was spread far and wide throughout central Europe during the first half of the second millennium BC.

This culture is named after a village in the Czech Republic, where the first artifacts associated with the Únětice culture were unearthed. Over 2,500 sites that were once occupied by the Únětice people have now been discovered, primarily in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Germany (about 500 sites have been found in the latter).

It seems the Únětice had peaceful relations with their neighbors. They built an extensive trade network that expanded their influence over a broad area of the European continent. Bronze artifacts and pottery manufactured by Únětice artisans have been found in areas where they did not have settlements, including Scandinavia, Ireland, the Balkans, and the Italian Peninsula.

X-ray fluorescence tests performed on the Nebra Sky disk in 2011 have offered some proof that the Únětice trading and bartering network really did cover an impressive distance. Much to the surprise of scientists involved in the testing, it was revealed that the gold used to create the disk’s inlaid images was harvested from the River Carnon in Cornwall, England. Nebra is more than 800 miles (1,350 kilometers) from Cornwall as the crow flies, which would have been quite a distance for traders and merchants to cover 3,600 years ago.

The Nebra Sky disk will be exhibited at the British Museum together with the Shropshire bulla sun pendant as part of the “The World of Stonehenge” exhibit in February 2022. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

UK Exhibit: Nebra Sky Disk And Shropshire Sun Pendant

While a replica of the Nebra Sky disk has now been launched into space, the real thing will soon be on the move as well.

In January, the Museum for Prehistory in Halle, Saxony-Anhalt will be loaning the disk to the British Museum in London. Placed on display alongside a 3,000-year-old Shropshire bulla golden sun pendant found in Britain, it will be a featured item included in a six-month-long exhibition entitled “The World of Stonehenge.”

Neil Wilkin, the British Museum curator responsible for arranging and managing this exhibit, explains its purpose and the importance of the Nebra Sky disk:

“The Nebra Sky disk and the sun pendant are two of the most remarkable surviving objects from Bronze Age Europe,” he told the BBC . “Both have only recently been unearthed, literally, after remaining hidden in the ground for over three millennia. While both were found hundreds of miles from Stonehenge, we’ll be using them to shine a light on the vast interconnected world that existed around the ancient monument, spanning Britain, Ireland and mainland Europe.”

Overall, the exhibit will feature hundreds of artifacts recovered from Bronze Age and late Neolithic age sites, spanning the broad historical era during which Stonehenge was designed and constructed. While Stonehenge was built about 1,000 years before the Nebra Sky disk was manufactured, they are united within the context of a shared cosmological, astronomical, and mythological framework.

People who lived in Europe during that long-lost time paid a great deal of attention to what was happening in the sky above them. They incorporated their astronomical observations into their spiritual belief systems, while also using them to track the changing of the seasons and other important events that impacted their daily lives.

Anyone interested in learning more about the practices and beliefs of Neolithic and Bronze Age Europeans can visit “The World of Stonehenge” exhibit starting early next year. The British Museum will officially open the exhibit on February 17, 2022, after which it will remain open until July 17.

Top image: The astronauts in the Nebra Sky disk spaceflight, which is also known as the Cosmic Kiss mission, with German astronaut Matthias Maurer on the far left . Source: Dbachmann / CC BY-SA 3.0 / ESA

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 15th, 2021

November 15th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: