On May 8, 2017, a drum of radioactive oilfield waste from Australia arrived at a remote West Texas disposal site operated by local oil and gas environmental services company, Lotus LLC. This drum of waste entered the United States aboard a Singapore Airlines cargo jet, appropriately packaged in a steel drum. According to files from the Railroad Commission of Texas, the state’s main oil and gas regulator, it contained the radioactive element radium at concentrations of 2,095 picocuries per gram. Those levels are more than 400 times the protective health limits designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for toxic Superfund sites and uranium mills, where fuel for nuclear bombs was once assembled.

The oil and gas industry produces an extraordinary amount of waste. Much of it is toxic, and it can be highly radioactive too. And since 1997 about one million barrels worth of oilfield waste has been brought to Lotus’s disposal site, situated off a dusty desert road located 19 miles west of Andrews, Texas (and just several miles from a massive solar array financed by Facebook and which provides energy to Shell’s fracking operations).

But according to correspondence with federal and state regulators, documents obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, and interviews with an industry whistleblower, DeSmog has found that the Lotus disposal site has at times struggled to safely manage the radioactive waste it receives from across the United States.

Despite this challenge, it is importing oil and gas waste from other countries too, and is expanding its reach internationally.

The company has relied heavily on a decades-old industry exemption passed in 1980 — known as the Bentsen and Bevill Amendments to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act — that classifies oil and gas waste as non-hazardous, thereby affording it little regulatory scrutiny. Meanwhile, Railroad Commission documents obtained via a FOIA request suggest that practices at Lotus’s remote disposal site have put the company’s workers and the environment at risk.

“The oil and gas industry has been really good at painting the picture that they are not a radioactive industry,” said Melissa Troutman, an Earthworks analyst and author of a 2019 report on oil and gas waste, “when in reality it produces a massive amount of radioactive material.”

A growing group of environmentalists, politicians, communities, and even the industry’s own workers have become increasingly critical of the fossil fuel industry, and see room for action under the Biden administration, though most attention has been placed on hot-button topics like climate change and methane emissions. But a small yet ardent band of advocacy groups have been focused on radioactive oilfield waste, long an industry problem but one that has metastasized in the fracking boom and potentially poses an even greater risk to the industry’s bottom line.

“Waste is the Achilles’ heel for these guys,” said Ted Auch, an analyst who has been closely tracking oilfield waste with the watchdog group FracTracker Alliance. “The entire industry operates on the notion that this stuff is relatively cheap and easy to get rid of. If they ever had to pay full price for the waste they produce, the industry’s cost-calculus crumbles.”

According to one calculation in a 2013 analysis co-authored by nuclear physicist and radioactive waste specialist, Marvin Resnikoff, if oil and gas waste were appropriately characterized, disposal costs could increase by more than half a million dollars for every well drilled.

DeSmog’s investigation raises serious concerns as to whether the waste being shipped to Lotus is being disposed of properly.

“If the industry was not exempt from hazardous waste law,” said Troutman, “the characterization of their waste would be far better, the tracking would be far better, and it would be harder for companies to manipulate the system like this.”

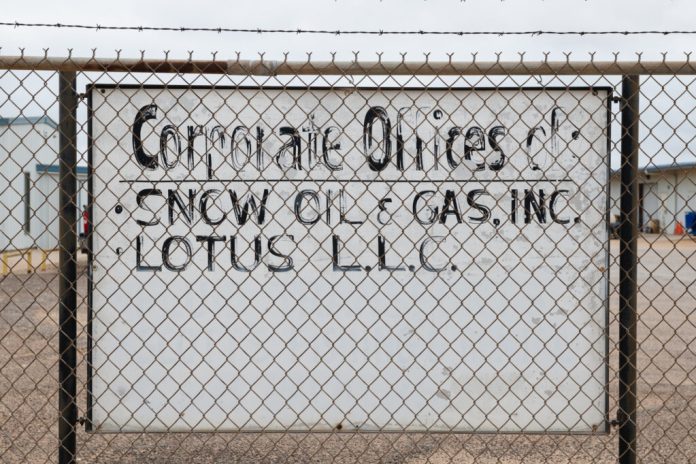

Who is Lotus LLC?

The EPA says the oil and gas industry generates an estimated 5 million cubic feet of radioactive sludge a year, much of it in tanks at the wellhead. That’s enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool every week, and this figure only includes sludge generated from conventionally drilled wells.

A radioactive “scale” forms on the inside of wellhead piping, and sludge and radioactive films that are often invisible to the naked eye also accumulate inside natural gas and natural gas liquids pipelines and processing equipment. According to a 1993 paper published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers, much of this material “must be handled as low-level radioactive waste and disposed of accordingly.”

While oil and gas waste may be considered non-hazardous under the Bentsen and Bevill Amendments, it is often too radioactive to be disposed of in a typical landfill. This is where special disposal at sites like Lotus come in, along with a handful of others across the country that are licensed to handle radioactive oilfield waste, including US Ecology in Idaho and Energy Solutions in Utah.

Lotus, a private company with about 75-100 employees, has permits from the Railroad Commission of Texas that enables the waste to be unloaded into pits, and crushed and mixed with water to form a slurry that can be more easily injected down a set of injection wells and into a salt cavern. When properly prepared, these massive domes of salt beneath the earth can be used as a subterranean locker, and the Department of Energy has deemed this an appropriate option for the disposal of radioactive oilfield waste. But Railroad Commission reports, such as one 2003 inspection, indicate that the waste is not always making it into the salt cavern, and rather Lotus “is only using the entire facility plant and decon facility for storage.”

The whistleblower corroborated this critique of Lotus, and described a situation during an informal visit in the time period of 2015 to 2016 in which the Lotus site had been overrun with stockpiled waste, with barrels piled up around the site. A longtime executive in the oilfield waste industry with firsthand knowledge of disposal facilities across the country, this whistleblower has requested anonymity due to ongoing industry legal obligations. They provided DeSmog with photos of the Lotus site from that period which convey damaged, rusty tanks marked with a yellow radioactivity symbol, a heaped dumpster of additional waste material, and several unmarked black barrels sitting on wooden pallets, without any liners or containment to prevent leaching or runoff. The whistleblower called the Lotus site “alarming and a potential environmental disaster for Texas” and “one of the most shocking facilities I have ever seen in my time in the oil and gas industry.”

DeSmog sent the photos to James Dillingham, the director of global operations with Lotus, who replied with a series of comments. Dillingham stated the photos “are not representative of how Lotus, LLC manages waste. These photos only illustrate a single instance where material was received and was under process for disposal, which was within the parameters of our licenses and permits.” Dillingham added, “Representing Lotus by way of publishing wording or photos in a manner that causes the public to conclude that material sent to our facility is or was handled otherwise will be considered libel. Accordingly, we will seek restitution under the law for personal and financial injury caused by any misrepresentation caused by this.”

Additionally, Dillingham supplied a response on behalf of his manager: “The pictures that are proposed to be presented in the article as previously poised are the property of Lotus LLC and are copyrighted and we don’t give permission to display those in any form or fashion and must be returned to us immediately. Additionally the entity or person who has conveyed these pictures to you or has somehow allowed them to become in your possession has violated the confidentiality clause they signed up for and their identity must also be revealed to us so that appropriate legal action may be conducted should these photos be publicly displayed and not returned or destroyed. You are requested to resolve this issue immediately so as to prevent further harm.”

Dillingham also stated that, “according to my manager, the photos you have provided are outdated and not an accurate representation of what is currently at the facility.”

On Sunday, April 4, 2021, DeSmog sent a photographer over the Lotus site in a small plane. The photos reveal the site contains a significant number of stockpiled barrels and containers. When the whistleblower reviewed these recent photos, they said the images suggest that many of the same issues remain — and may have worsened — since their earlier site observation at the Lotus facility during the 2015-2016 timeframe. They pointed to what appeared to be significant amounts of stockpiled TENORM wastes held in numerous damaged, rusted, and degraded tanks or barrels stored directly on an unlined surface without proper containment to prevent leaching, runoff, and other direct risks to groundwater and surface contamination.

The whistleblower also noted that many of the large open tanks in the photos appeared to show high volumes of filter socks and scale from pipes used during oilfield operations — both filter socks and pipe scale are known to have a high radioactive signature. The whistleblower said these were apparent compliance issues, with possible violations including a lack of proper containment around the site, lack of lined protection to the surface, and significant volumes of stockpiled TENORM wastes that have yet to be processed or properly disposed.

“I can’t confirm these pictures,” Lotus operation manager Dan Snow replied via email. In response to questions about the nature of the stockpiled waste and alleged violations, Snow said, “as always, our plant is in full production mode handling all types of RCRA exempt waste as it is shipped to the facility. Waste comes in all types of packaged and unpackaged methods and it can even come in a dump truck so long as the transporter follows the DOT [Department of Transportation] and RRC rules. Waste may even come in the form of abandoned vessels that have to be taken apart to remove the waste.” Snow stated Lotus operations follow all appropriate state and federal rules and permits.

DeSmog sent the recent aerial photos to the RRC for review and asked the agency to comment on the alleged violations and compliance issues. “Our agency conducts inspections to ensure compliance with all rules in place to protect public safety and the environment,” said R.J. DeSilva, the RRC Director of Communications. He directed DeSmog to a web portal that features inspection information for oilfield facilities. It shows that the most recent RRC inspection of the Lotus site in Andrews County occurred on March 29, 2021 and found no compliance issues, stating, “No violations were observed in this inspection.”

Every single day, hundreds of barrels of oilfield waste may arrive via truck at Lotus. The waste comes from oil and gas fields across Texas (including a set of wells operated by Chesapeake and located on the grounds of the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport) and neighboring states like New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. It also comes from offshore wells in the Gulf of Mexico and some of the last remaining oil and gas platforms off the California coast, operated by ExxonMobil. The waste arrives from states as far as Alaska, North Dakota, Michigan, Colorado, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, and even states like Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa, which have no significant oilfields but are crisscrossed by pipelines that fill up with radioactive sludge. The Railroad Commission files indicate that radioactive sludge also builds up at compressor stations, and this waste may be shipped to Lotus.

The files indicate that virtually every major operator in the oil and gas industry has sent their waste to Lotus, including ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Occidental, Anadarko, ConocoPhillips, Chesapeake, as well as midstream companies like Kinder Morgan and ONEOK. DeSmog reached out to these companies who were mostly unresponsive to questions about the site and its operating practices. “At BP we remain committed to safe, reliable, and compliant operations,” stated Cameron Nazminia, Corporate Communications Manager with BP, one of the few companies that replied to questions about Lotus.

“These operators took a lot and got in over their heads.”

A longtime oilfield waste industry insider on Lotus LLC

While the process of grinding radioactive waste into a slurry and injecting it down a hole may seem simple, the whistleblower explained that performing the process safely is technically challenging and operationally expensive. Radioactive oilfield waste is referred to as NORM, or TENORM (Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials), and a facility licensed to dispose of it can charge waste generators high disposal fees, sometimes as high as $200-250 per barrel, versus an average of around $8 per barrel at a facility simply licensed to dispose of the industry’s non-radioactive waste, according to the whistleblower.

“What happened is they just got overrun with TENORM waste material being delivered from all over the country,” the whistleblower said of Lotus, “they were not technologically or operationally capable, and did not properly manage what was accepted for disposal at the facility. These operators took a lot and got in over their heads.”

James Dillingham, the director of global operations with Lotus, said that, “Any NORM contaminated material present at the site is being processed in accordance with our license and permits.” He said that in recent years, “we have been able to increase daily capacity by having more employees, more offload areas, more efficient pumps, and better process knowledge.” He also pointed out that Lotus was licensed to receive all manners of “nonhazardous oil and gas waste” and that not all of the waste it received was radioactive. “I only say that to illustrate the fact that the items that appear to be accumulating may not necessarily be classified as radioactive waste, nor a waste that has other hazardous elements,” he said.

According to the company’s own quarterly reports to the Railroad Commission, Lotus took in over 10 times more waste in 2013 (83,895 barrels) compared to a decade earlier (6,673 barrels in 2003). When asked how the company has been able to handle the enhanced waste stream brought on by the fracking boom, Dillingham said, “We are currently investing heavily in new technology that will help us process the more difficult types of waste that are plaguing the industry.”

“We believe this technology will allow us to provide a more economical yet equally as secure solution to the industry,” he added. “In the meantime, any difficult or time-consuming materials requiring extended processing are securely temporarily stored in a restricted area adjacent to the processing/disposal facility with constant surveillance, air monitoring, and dosimetry.” (Dosimetry refers to the science of measuring the radiation dose absorbed by the human body.)

Furthermore, he added, the facility is subject to annual audits by the Railroad Commission, the Texas Department of State Health Services, clients, and other groups, and also “more frequent surprise audits.” “These audits would reveal any discrepancy between the Lotus operation and the items that are allowed under the licenses and permits while also obviously revealing any potential weak points that could cause increased risk to human health and safety,” he told DeSmog.

A risk to workers

But as the more than 2,000 pages of records and reports reviewed by DeSmog show, Lotus has experienced a number of concerning incidents that began shortly after the site opened in 1997. This history includes radioactive waste leaking into the ground and barrels of waste regularly being piled on site for extended periods of time. Local community members also raised concerns about workers being exposed to radioactivity.

One particularly damning Railroad Commission inspection occurred in May 2003. “There were several metal drums with corroded sides and/or bottoms located at various spots within the fenced process facility,” states the report. “The deteriorated condition of these drums has allowed some NORM contents to escape to the ground.” The inspection suggested that rain received in the days prior to inspection had carried contamination to “low lying, muddy areas near the gate.”

Handwritten notes in the May 2003 report show that drums of waste had been moved around the site “only for the purpose of a cosmetic coverup,” again suggesting the waste was not being appropriately disposed of by injection into the salt cavern, but instead being stored on the site’s grounds. Furthermore, the notes express concern that one of the injection wells has been inappropriately “abandoned” and that the “casing perhaps could be corroded/wear away gradually” and if the well were not properly isolated, the situation could “be harmful to our drinking water.”

In May 2004, Railroad Commission Assistant District Director Mike Houston visited the Lotus facility and noted, “There are still some pollution concerns.” On a walkthrough inspection, Houston noticed “leaking steel drums” whose contents had “either partially spilled or [had] the immediate possibility of leaking onto the storage yard soils.” The letter stated that the conditions observed violated Texas Statewide Rule 8, which regards water pollution and oilfield waste pits.

The report also addressed worker radioactivity risks: One steel drum at the Lotus site measured 5,800 microrems per hour — a measurement used to classify how much radioactivity would be absorbed by a human being — an amount “which can be a health threat to coworkers, given extended exposure time.”

When DeSmog ran that number by Worcester Polytechnic Institute nuclear forensics scientist Marco Kaltofen, he explained that the level was worrisome. “At 5,800 microrems an hour, it would take only about two days to get your typical ANNUAL dose of industrial/medical radiation,” Kaltofen stated in an email, referencing dose limits set by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission for the nuclear and medical industries. These limits, however, do not apply to oil and gas workers.

But perhaps most concerning among the public records DeSmog received from the Railroad Commission was a letter sent to the regulatory agency in October 2000 by the “Concerned Citizens of Andrews County, Texas.”

“We regret having to write you [a] letter anonymously, but because of the nature of the individual involved, we fear not only reprisal from him personally, but also from his battery of attorneys,” the letter states.

The Concerned Citizens explain that they “have made trips to a facility operated by Lotus, L.L.C. in western Andrews County” and found drums of radioactive waste stacked along the fence line of the facility, “a large pile of dirt and rocks on the north fence line that appears to be radioactive contaminant as well,” and a trio of 500-barrel frac tanks that “are completely full of what appears to be radioactive waste.”

According to the letter, Lotus workers told the Concerned Citizens that some of this waste had been stored on site “in excess of two years.” The Railroad Commission was not able to provide a direct response to the question of how long waste is allowed to sit on site before having to be disposed of down the injection well and into the salt cavern.

“These employees have also expressed concerns for their health from long term exposure to this material,” the letter adds.

Attempts to locate the authors of the anonymous letter were not successful. DeSmog presented the letter to Lotus, along with a copy of the June 2003 inspection report that noted leaking waste barrels.

“As it relates to the concerns presented in the letter, the citizens are certainly entitled to bring awareness to potential problems; however, in this particular case, it does not appear that there was anything that was causing any elevated health, safety, or environmental risk,” said Dillingham.

He also defended the company’s efforts to protect its workers from radioactivity contamination. “I can confirm that at the time of the filing, and continuing through today, all employees whose job duties involve potentially making an entry into a restricted area are monitored in the dosimetry program outlined in the Lotus Health Physics Plan,” said Dillingham. “As a company that is licensed for handling this type of waste we have our own health physics plan in place…Lotus workers work around NORM all day, every day, and given that we have never had a person exceed the dose limit, ever, and we have been in business since 1997.”

But Texas regulators do not appear to be addressing the worker safety questions raised in the files received from the Railroad Commission.

DeSmog informed the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) that Lotus records indicate sloppy operating practices that put both workers and the environment of Texas at risk. “DSHS does not regulate the Lotus disposal site,” replied Chris Van Deusen, the agency’s Director of Media Relations.

When asked by DeSmog what tests, inspections, or surveys DSHS has conducted of Lotus workers to ensure they are appropriately protected from radioactivity, Van Deusen again stated, “DSHS does not regulate the Lotus disposal site.” OSHA, in previous correspondence with DeSmog, has conveyed that oilfield workers are not at risk from radioactivity, yet the agency has never formally studied the issue.

The whistleblower expressed concern that Lotus “poses a black eye” to the oil and gas industry and Texas regulators.

“It is exceedingly maddening that nothing is actively being done to properly address these issues,” said the whistleblower. “Myself and others have been pounding the table on this and speaking with the Railroad Commission in Texas for nearly 10 years now. It is there, everyone knows about it, and no one can say they don’t know. Yet, the regulators have not taken any meaningful efforts to correct this dangerous and poor operating practice.”

Importing radioactive waste

A lack of oversight when it comes to domestic waste, however, isn’t the only challenge. The 1980s industry exemption also makes it easier to import radioactive oil and gas waste produced outside the United States.

Because this waste is generated in an oilfield, unlike radioactive waste generated by the nuclear or medical industries, the notorious Bentsen and Bevill Amendments enables it to move around the U.S. insufficiently monitored — and into the U.S. from other parts of the world entirely unmonitored.

In DeSmog’s correspondence with EPA, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the Railroad Commission of Texas, it has become apparent that no federal or state agency appears to be tracking or monitoring shipments of radioactive oilfield waste into the United States from foreign countries, and none of these agencies appear to have regulatory authority over such international shipments. U.S. Customs and Borders Protection has not responded to questions on the matter.

According to Jeff Tyson, Head of Environmental Research and Analytics with the Texas-based firm Waste Analytics, oilfield waste generated in Mexico, for example, has been transported across the border for disposal in the United States. At least 534 loads of waste, said Tyson, was transported between October 2005 and March 2006, and disposed of at a treatment facility in Starr County, Texas.

Lotus’s first international shipment was 65.5 barrels of soil and sludge that arrived from Alberta, Canada in November 1999. The files DeSmog obtained from the Railroad Commission records request reveal that more than 450 barrels of waste from Canada arrived between 1999 and 2004.

Information provided to DeSmog by Dillingham shows that Lotus had imported 750 barrels of oilfield waste from Australia between May 2017 and November 2019 — the first barrel arrived by plane, the rest have been transported by ship.

“We reached out to the EPA and the NRC asking if there were any objections to importing Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA) exempt E&P waste containing diffuse amounts of NORM,” said Dillingham. But as DeSmog has learned, no specific permits appear to be necessary in order to import radioactive oilfield waste into the country.

Presently, Lotus is in the process of expanding its overseas operations. The company has already established an office in Watford, England, part of a joint venture tasked with decommissioning, decontamination, and waste management services to the oil and gas and industrial sectors in Europe, UK, and Russia.A map passed alongby Dillingham conveys that Lotus has a presence in oilfields on every continent but Antarctica. “Our international services include NORM training, surveying, consulting, decontamination and a whole gambit of other non-NORM related services relating to decommissioning and well servicing,” said Dillingham. “As it relates to importing NORM waste, it has never been our long-term strategy. The ability to import a stockpiled volume of material can help solve an immediate need, but the long-term objective is to help countries develop local solutions.”

Wording on the website of the company’s England-based joint venture, Lotus ZRG, appears to promote Lotus’s disposal site in Andrews, Texas: “Welcome to Lotus ZRG – from our licensed facility in Texas, we provide NORM decontamination, transportation and disposal internationally to wherever our clients’ facilities require us.”

Current federal laws give the company confidence that these imports are legitimate. “As it relates to transportation, the requirements are based on the same regulations for road or by ship,” said Dillingham. “I certainly didn’t intend on implying or stating that it wasn’t regulated. I said that it is not federally regulated. NORM waste is not defined as a ‘radioactive waste’ by the NRC, therefore not under the Atomic Energy Act. Further, wastes strictly associated with the exploration and production of oil & gas are exempt from EPA hazardous waste definitions under RCRA. Wastes meeting this exemption are regulated on the state level.”

When Lotus asked the EPA in an October 12, 2016 email whether or not the company could import radioactive oilfield waste, the agency replied on November 7, 2016, stating: “Based solely on the information provided by Lotus, the waste…is exempted from federal hazardous waste regulations” and “as such…may be imported to the United States without a hazardous waste notification.” The Railroad Commission, in a December 2016 report, recognizes that “EPA does not regulate the waste” and states that Lotus’s permits with the state agency do not “require or restrict the acceptance of offshore (outside US waters) or foreign oil & gas waste.”

A 2018 letter from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission stated that because the federal agency has no regulatory authority over the oil and gas industry’s radioactive materials, “it would not meet the…definition of radioactive waste.”

“EPA has no records of Lotus importing oilfield waste,” stated an EPA spokesperson, and the agency is not keeping track of how much foreign oilfield waste is entering the U.S., how it enters the country, at which port it enters, or how radioactive it is.

“As we lack jurisdiction over this material,” Nuclear Regulatory Commission spokesperson David McIntyre told DeSmog, “we do not track its movement or disposal.”

More than half a dozen other analysts and policymakers DeSmog spoke to for this story were unaware that oilfield waste was being imported into the United States.

“It never occurred to me that we might be importing toxic and radioactive oil and gas waste from other countries,” said Amy Mall, a senior advocate with the environmental group Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Mall has been tracking oil and gas waste and its impacts for over a decade and is set to release a new report on the topic with NRDC shortly. “Americans are used to the situation where we’re the ones shipping waste overseas to other people who don’t have the ability to stop it, but in this case that has been reversed,” said Mall.

“I do a lot of consulting on import and export of radioactive material and frankly I don’t think there is any database anyone maintains to know what goes in and out of the country,” said Rick Jacobi, the owner and principal consultant at Jacobi Consulting, a former General Manager of the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Authority and current consultant for domestic and international companies on the management of radioactive material and nuclear facilities. “I don’t think that U.S. Customs maintains any database, and to my knowledge there is no national database.”

None of the regulatory agencies in Texas involved in oil and gas, including the Railroad Commission, the Texas Department of State Health Services, or the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, have “jurisdiction over the import or export of radioactive waste,” Jacobi added. “Imports and exports are regulated exclusively by the federal government.”

“Commercial facilities have a financial incentive to accept the waste and generate revenue regardless of where the waste was generated,” added Jeff Tyson, with Waste Analytics. “As long as the facility is permitted to accept the waste, there is no legal or economic reason for them to reject it.”

Meanwhile, there may be the need for a much larger investigation. “Companies who are licensed to deal with this waste are trying their best to provide a responsible solution but are often the only ones who get criticized or reviewed,” said Dillingham. “The bigger problem is those who don’t even bother to get licensed and protect their staff.” He said the oilfields of Texas and Oklahoma contain several large facilities of this nature, which accept NORM waste without licenses or proper screening controls in place. Dillingham adds that Lotus’s salt cavern is approaching capacity, and the company is presently in the process of creating another one — using a process called solution mining — out of the bedded salt deposit at the property in Andrews County. Once permitted for waste disposal it could have disposal capacity for up to another million barrels of oilfield waste.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 25th, 2021

April 25th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: