ACEH, Indonesia – It’s just another day in Banda Aceh, the capital city of Indonesia’s only Shariah-regulated province and one of its poorest.

Officials—mostly men—from the Sharia police are gathered at Taman Sari, a popular public park at the heart of the city. Among the scant crowd is a group of college girls and photojournalists jostling to get the perfect shot. In the middle of the park’s arena, a woman cloaked in a white jilbab with her face covered with a mask, is seated on her knees on a carpet. She’s accused of a crime that wouldn’t even be considered a crime anywhere else in Indonesia: meeting a man who is not her husband.

As an officer reads out the crime, another woman, dressed head-to-toe in a brown jilbab with her face covered, gets ready with a cane next to her.

On cue, the woman in brown delivers swift blows on the accused’s back 22 times. Once it’s over, the accused gets up and leaves. Three more floggings of men by men for other crimes follow.

Public floggings are business as usual in Aceh, a uniquely conservative province in a country that has the world’s largest Muslim population. Floggings are highly publicised and usually well attended. What’s uncommon, though, is flogging delivered by a woman, a contract employee of the Sharia police.

In 2020, just before the pandemic gripped the world, Aceh’s Sharia police officially unveiled an all-women flogging squad—a first in the country where the punishment has drawn international attention, and criticism, for years. VICE World News attended the first flogging of 2022 by a woman flogger, in November, and met two women floggers to understand their role in Sharia policing and society.

Aceh has been a religious outlier in the officially secular archipelago country. Once in the grips of decades-long violent independence struggle from the central government, Aceh’s Sharia law was formalised in 2003 when Jakarta granted it special authourisation. The semi-autonomous status allows Aceh to pass its own laws and, over time, hundreds of Sharia-based ordinances have come to dominate public life—from clothing restrictions, to banning women to sit astride motorcycles, to intermingling of opposite sexes, playing live music and drinking. One study found 442 local Sharia regulations enacted between 1999 and 2012.

Public floggings are business as usual in Aceh, a uniquely conservative province. What’s uncommon, though, is flogging delivered by a woman.

The idea of inducting a woman flogger, according to Muhammad Rizal, the head of Aceh’s Sharia police, is to tackle the problem of rising crime among women. A female flogger is better placed to punish a woman because a male flogger’s delivery is “too harsh,” he added.

“The purpose of flogging is not to torture the person, but to make them feel guilty,” Rizal told VICE World News. “That’s why, if the perpetrator is a woman, then the flogger should be a woman too.”

The Sharia police go to great lengths to conceal the identities of women floggers from the public. Rizal said that is so that they don’t face retaliation or other forms of revenge later on. “I myself don’t know the real identities of the women floggers,” he said.

The optics of inducting women floggers is a matter of pride for the Sharia police in a country where restrictions on women often make it to international headlines. In the past, they’ve taken international media on patrols to demonstrate how they maintain a strict moral conduct on the streets, especially for women.

In official data shared by Sharia police with VICE World News, crimes against morality, such as unmarried men and women caught together, have seen a steep drop in 2021 as compared to 2018. For instance, khalwat or when an unmarried man and woman are in a secluded place together, was reported 90 times in 2018. In 2021, that number was down to 8. The Sharia police attribute this to flogging. Activists disagree.

“It’s performative—the floggings in general and the induction of women floggers,” M Adli Abdullah, an Acehnese historian and expert on the province’s Islamic law, told VICE World News. “Floggings are a part of the image building of the Sharia law by the Aceh police. I don’t believe it’s reducing any kind of crime.”

Banda Aceh, the province's capital and largest city, which has a population of 252,899, has four women floggers. There are 8 women floggers across the province. Roslina A Djalil, the head of Sharia law enforcement who inducts women floggers, told VICE World News that they are still an unusual sight.

VICE World News spoke to two women floggers on the condition of anonymity. They are identified with pseudonyms. They came in their flogging gear and revealed little about their personal lives out of concern of being identified.

Mariam, Aceh’s first woman flogger, wanted to become a lawyer but joined the Sharia police instead in 2006 and then was appointed by the prosecutor to become a woman flogger in 2018. “I never thought of becoming a flogger but when this regulation was made, I was ready for it,” the mother of four children told VICE World News.

The act of flogging doesn’t faze her either. “It’s an order from the government of Aceh” she said. “Since I’m human, I used to shake out of nervousness at first. But honestly, there’s no fear because I consider it a duty to God.”

“Since I’m human, I used to shake out of nervousness at first. But honestly, there’s no fear because I consider it a duty to God.”

She is aware that she holds a special position in a male-dominated field, but doesn’t know whether it’ll inspire other women to follow suit. “Maybe the bigger lesson for them is to watch the flogging and not do anything that’s forbidden,” she said.

Reha, another flogger who also joined in 2018, said that women floggers have “really helped” maintain law and order. “Back then, there were many women perpetrators [of Sharia crimes],” she said. “So women floggers had to be inducted to handle [this crime].”

Religion is a part of life, even in policing. But Djalil said that inducting floggers requires rationale and training. “Every aspect of flogging is regulated by the procedural law: How to whip, the length of the cane, the diameter, everything,” she said. Djalil, who’s been in the Sharia law service for 13 years, held out a cane at arm’s length to demonstrate, saying the more the arm is pulled back, the stronger the lash is. The cane must not land above or below the upper back too.

“The intensity of the lashes should be in accordance with the Qanun (Sharia law),” she said. ”It shouldn’t be so weak that people who are watching aren’t satisfied, or think the punishment isn’t painful enough.”

An overarching message by the Sharia police and floggers is the importance of stoicism towards the accused.

“I’ve trained some women who can hit the accused, but they felt sorry for them too,” said Djalil. “[The biggest quality I look for] is their ability to not be empathetic.” Mariam said that she once flogged someone she personally knew, but didn’t feel any empathy because that’s what the job demands.

Mistakes are rarely tolerated, and can result in expulsion from the post.

Rizal said that men and women are punished equally. But floggings of women have especially caught international attention.

In 2014, the Sharia police flogged a 25-year-old woman for adultery even though she was handed over to them by vigilantes who gangraped her and doused her with sewage water. Early this year, a woman was flogged 100 times for adultery while the man involved, who denied the accusations, received just 15 lashes.

“The fact that the woman had already collapsed once and was still forced to undergo more flogging shows a complete lack of compassion and care for her well-being and health,” Amnesty International Indonesia said of the incident early this year. “Both the use of flogging as a punishment and the criminalization of sexual relations outside marriage are clear violations of international human rights law.”

The rights group also called flogging a “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” that “may amount to torture.”

The Qanun Jinayat, or Aceh’s Islamic criminal code, sets out legal punishments that prescribes imprisonment and fines apart from flogging. But human rights reports found that flogging is indiscriminately used. Rizal, the head of Sharia police, said that floggings aren’t random and only follow investigations and trials.

Hundreds of Sharia-based ordinances dominate Aceh’s public life— from clothing restrictions and to banning women to sit astride motorcycles to intermingling of opposite sexes.

“If the investigation doesn’t turn up enough evidence, the person is free,” he said. “If not, then we arrest and the court decides the punishment.”

When asked for data, the Sharia police station in Banda Aceh said it didn’t have records of the number of floggings they had conducted in recent years. But one human rights report shows 428 floggings in 2013, followed by 515 in 2014 and 548 in 2015 across Aceh.

In 2019, the Aceh police released a budget report that showed that each flogging costs the provincial government nearly $1,000 (IDR 15 million), which includes food arrangements, and facilitating security, health officers and witnesses. Aceh is one of Indonesia’s poorest provinces, and this kind of spending has irked local activists.

“The court process is not even transparent so we don’t know what goes on in the trials that prescribe floggings,” Raihal Farjri, a women’s rights activist in Banda Aceh, told VICE World News.

A report by Indonesian researcher Dina Afrianty also found Aceh’s Sharia courts don’t meet the principles of justice. “Many decisions [by the judges] include a checklist of personal attire, such as underwear, leggings, and bras,” the report states. “The system appears designed to shame and humiliate, demonstrating an unpleasant obsession in the community with sexual activity at the expense of other more serious social concerns.”

Farjri said that floggings disproportionately impact women accused. “I’ve seen men walk away after floggings with smiles and relief on their faces,” she said. “But women face social ostracisation because patriarchy instils shame in them. The media blames them too.”

In 2012, a teenage girl died by suicide after she was apprehended by the Sharia police in public and accused of prostitution. Farjri recounted another case where a young woman died by suicide after she was flogged on charges of having a boyfriend.

“Women, sometimes, have to leave their villages because of this social stigma,” she added.

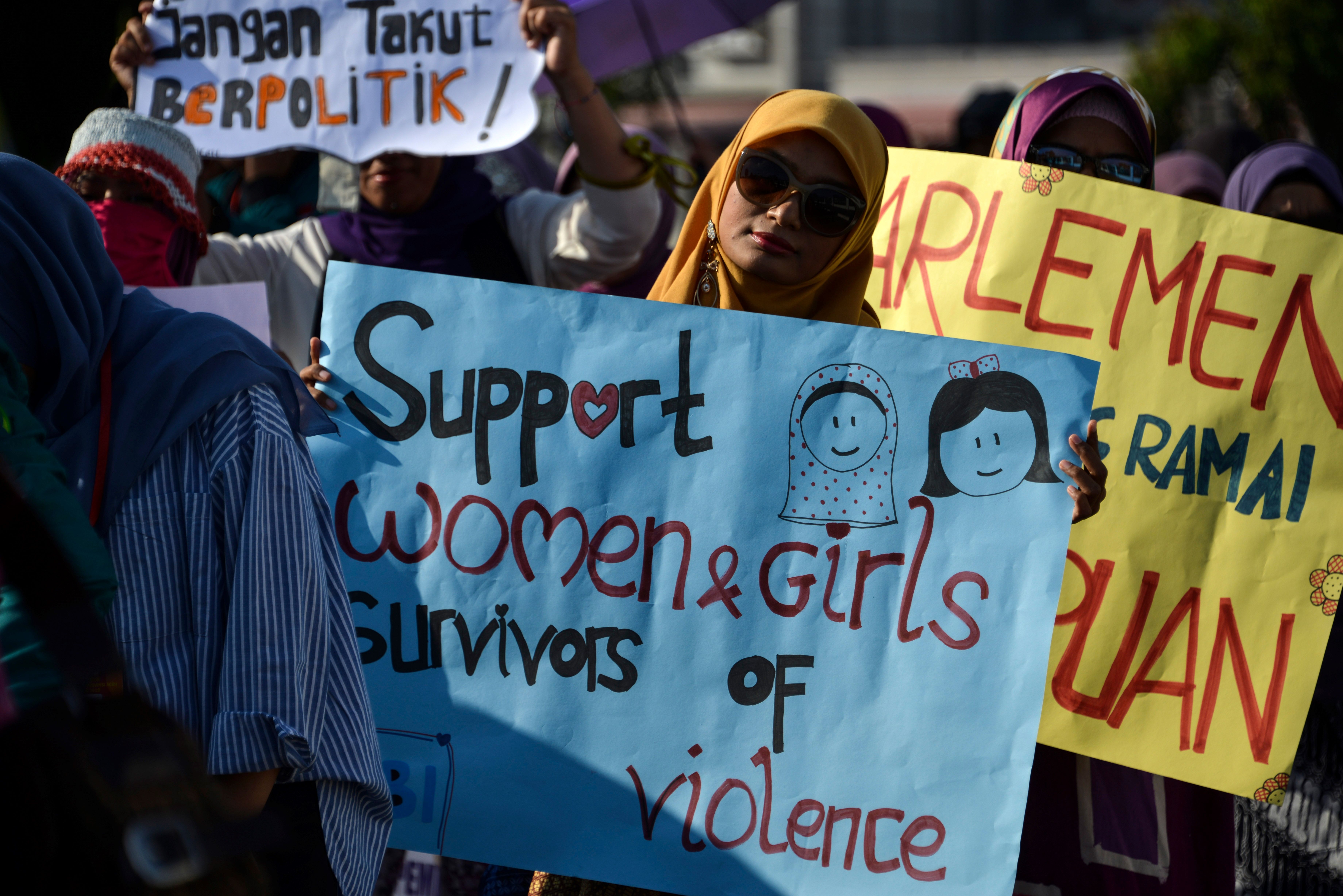

Acehnese women and local NGOs have been campaigning to revise Qanun Jinayat, which was originally implemented to address sexual violence. The province has a long history of sexual violence against women, particularly during the armed conflict that is estimated to have killed 15,000 between 1976 and 2003. Aceh is peaceful now but the scars of sexual violence are still raw.

Data shared by the Sharia police shows only two cases of sexual violence between 2016 and 2021. The majority of crimes, according to the police, are those against morality.

But activists say official data belies the bigger problem of sexual violence. “Sexual violence is rising and flogging doesn’t change that,” said Fajri. “The government should revise the Sharia regulations.”

To local activists, flogging for sex crimes isn’t a deterrent.

“The floggings are too mild a punishment,” Azharul Husna, the media coordinator of Kontras Aceh (The Commission For The Disappeared and Victims of Violence), told VICE World News.

“Most male perpetrators prefer flogging to jail time because once it’s done, they can go back home, often to a place where the victim is still living. Some perpetrators with connections can even turn the verdict to their favour and choose flogging. It’s completely ineffective.”

“Sexual violence is rising and flogging doesn’t change that. The government should revise the Sharia regulations.”

The global outrage around flogging, Husna added, is a distraction from the critical shortcomings of Qanun Jinayat, which they are fighting. For instance, it doesn’t recognize sexual violence apart from rape and sexual harassment. The Sharia punishments also overrides Indonesia’s historic sexual violence law that was passed this year. That law expands the definition of sexual violence to include abuse such as forced contraception, non-physical abuse and sexual slavery, and enforced harsher imprisonments for those charged.

Farjri said that international media misses their actual struggle because of global Islamophobia.

“When they look at Aceh’s flogging, they talk about Islam, the Sharia law, and the supposed oppression of women,” she said. “Look at countries that give out death penalties or 100-year prison sentences. Or Duterte and the people who died in his war on drugs. Those are so much worse than flogging. Do people bring up religion then?”

Farjri said that lasting change will only happen if people focus on the core problems of injustice and inequality.

“I have hopes that one day, the Qanun will be revised and women and children will be better protected,” she said, “But people need to look beyond religion and address the structural issues of Sharia punishments instead.”

This story was produced with support from the Round Earth Media program of the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Follow Pallavi Pundir on Twitter.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 27th, 2022

December 27th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: