The world of ancient Europe is full of unique myths, legends, heroes, and gods, many of which have survived through time to the present day. In many ways, these legends shaped the identities of modern European nations – lending inspiration and hope from generation to generation. It is no secret that many of the most intricate myths and legends come from the Norse peoples, immortalized in the Viking Sagas and their vibrant mythology. But there’s one from Germanic mythology that is often unjustly overlooked – the story of Wayland the Smith. This very old legend is one of the finest Germanic myths. And did you know that it shows parallels to the ancient Greek story of Achilles? In this article, we will unravel the story of Wayland the Smith and explore the deeper meaning it carries. Was he a god? Or a hero immortalized into legend? Let’s find out!

Earliest Mentions of Wayland the Smith In The Germanic World

Pan-Germanic mythology certainly does not lack in colorful, heroic figures. From the elaborate stories of the Norse gods , from giants and elves to Odin, Thor, and Loki, these stories are filled with all sorts of fantastical figures. But we don’t often hear the name of Wayland the Smith, even though he is widely known in these stories.

Wayland the Smith is a figure for whom there is evidence in almost all Germanic languages. He is recorded throughout history under various names. In Old Norse, he is Völund and Velentr; in old High German, he is Wiolant; in Old Frisian, Welandu; in Old French he is Galant; and in Old English, Wēland. Ultimately, all of these names stem from Proto-Germanic Wēlandaz, meaning “ the crafting one.”

The earliest dated mention of Wayland is, interestingly, from a coin. More precisely, from a gold solidus coin. It was discovered by accident in 1948 in a field near the village of Schweindorf in Ostrfriesland (East Frisia) Germany, right near the coast. At first glance, the coin is not remarkable. Often the solidi coins from these regions bore inscriptions of local prominent men. But this one seemed different, as it bore a runic inscription ᚹᛖᛚᚩᛞᚢ ( welandu, i.e. “Wayland”). It is also, coincidentally, one of the oldest inscriptions relating to Old Frisian language. The coin has been positively dated to somewhere between 575 and 600 AD.

Wayland the Smith gold solidus coin found in Germany in 1948 and dating to 575-600 AD. (HansFaber / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Wayland the Smith is also prominently mentioned in Early English history. Most mentions indicate that the legend of Wayland was extremely popular in the earliest stages of the medieval period and certainly before that. One of the crucial mentions dates to the early 8 th century AD and is found carved into what is known as Franks Casket .

Franks Casket and the story about Wayland the Smith carved into one side of casket (left in the photo). This is a very famous artifact. (British Museum / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The story of the discovery of this casket is fascinating to say the least, but its origins are undisputed. This early Anglo-Saxon artifact is a masterful display of Anglo-Saxon runes, and a unique mixture of scenes: some are from the Bible, some relate to the history of Rome, while one is related to German mythology . And that last one is the story of Wayland the Smith. On this casket in exceptional carvings, the myth of the cunning smith is depicted in detail. Interestingly, opposite to this image, on the same panel, is the depiction of a Biblical scene: the Adoration of the Magi .

In England, visual scenes that depict Wayland are numerous. Franks Casket is simply the most famous one. There have been discoveries of carvings at Halton-on-Lune in Lancashire, and on stone crosses in Bedale and Sherburn in North Yorkshire, and at Leeds in West Yorkshire. And most of these depictions present the same details from the same story. Which brings us to the heart of the matter: the legend of Wayland the Smith.

This legendary story is almost identical in every instance throughout the Germanic world. In it, Wayland is a smith of great renown. However, he is at some point captured by a cruel king of the Njars, Níðuðr.

Revenge on Cruel Níðuðr: How Wayland Flew Away

The cruel king Níðuðr imprisons Wayland on a remote island and orders him hamstrung to prevent his escape. Hamstringing involves severing of the hamstring tendons, essentially crippling the victim. Thus crippled, Wayland was forced to forge items of great quality for the king. Further injustices were done upon Wayland by cruel Níðuðr. He took Wayland’s ring, given to him by his wife, and gave it to his daughter. He also took Wayland’s renowned sword for himself.

Völund’s (Weyland) smithy in the center, Níðuð’s daughter to the left, and Níðuð’s dead sons hidden to the right of the smithy. Between the girl and the smithy, Völund can be seen as an eagle flying away. From the Ardre VIII stone that shows ancient figures from Norse mythology. ( Public domain )

In most versions of the story, Wayland succeeds in tricking the king in one way or another. In the Old Norse sources, he manages to slay the king’s sons, fashioning goblets out of their skulls and jewels out of their eyes. These he sends to the king and his family. He also rapes the king’s daughter, before fashioning a magical cape with wings, which he uses to fly away from the island. In some versions, he fashions special wings that help him escape. In this way, his story is similar to the iconic Greek Icarus legend.

Some of the most detailed mentions of Wayland come from the Old Norse period. By far the most popular of these is one called the Ardre Stones . These historic rune and image stones, dated to as early as the 8 th century, have become the unmistakable symbol for the art of the Vikings. One of these stones, Ardre VIII, depicts a plethora of the most important Norse myths – including depictions of Thor, Odin, Baldr, and Loki – but also of Wayland the Smith at his forge.

The Norse Völundarkviða is also the crucial source of Wayland’s story. It is a mythological poem, translated as The lay of Völund, and is a part of the world-famous Poetic Edda .

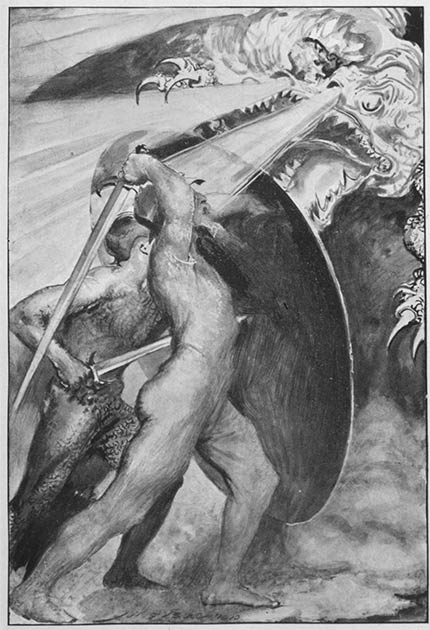

Beowulf, shown here slaying the dragon, is both a character and a long Old English poem (975-1025 AD). And in the book Wayland the Smith is also mentioned. ( Archivist / Adobe Stock)

The Legendary Metal Craftsmanship of Welund

In Old English sources, Wayland is mentioned surprisingly often. There are two very important sources for his legend, both of which provide important parallels to those of the Old Norse sagas. This shows that the pan-Germanic mythology survived in the Anglo-Saxon tribes even well after their migration to the British Isles. The first one we’ll mention is from the Old English poem, “ The Lament of Deor ”, which was a part of the 10 th century Exeter Book.

The poem consists of various accounts of several figures of Germanic mythology, all of which suffered in some way. The poet, Deor, then compares his own fate with theirs. He opens the poem with the story of Weland (Wayland):

“Welund tasted misery among snakes.

The stout-hearted hero endured troubles

had sorrow and longing as his companions

cruelty cold as winter – he often found woe

Once Nithad laid restraints on him,

supple sinew-bonds on the better man.

That went by; so can this.To Beadohilde, her brothers’ death was not

so painful to her heart as her own problem

which she had readily perceived

that she was pregnant; nor could she ever

foresee without fear how things would turn out.

That went by, so can this.”

Here we can see the crucial elements and figures in Wayland’s story: The brave hero endured trouble at the hands of Nithad (Níðuðr), but eventually he impregnated Nithad’s daughter, Beadohilde (Böðvildr) after killing her brothers.

However, one far more important poem also mentions Wayland, the legendary story of Beowulf. This poem has been dated to as early as 975-1025 AD, but without a doubt it has older origins. In the poem, Beowulf the legendary hero, wears a chainmail shirt that is crafted by Wayland:

“Onsend Higeláce, gif mec hild nime,

beaduscrúda betst, Þæt míne bréost wereð,

hrægla sélest, Þæt is Hraédlan láf,

Wélandes geweorc. Gaéð á wyrd swá hío scel.”

Several translations of this passage exist:

1

“No need then

to lament for long or lay out my body.

If the battle takes me, send back

this breast-webbing that Weland fashioned

and Hrethel gave me, to Lord Hygelac.

Fate goes ever as fate must.”

2

“Send to Hygelac, if I am taken by battle,

the best of battle-shirts, that protects my brest,

choicest of garments, that is Hrethel’s relic,

Wayland’s work. Fate takes its course.”

The Old English Legend of the Invisible Smith

Wayland’s Smithy is a unique location in England, located close to the village of Ashbury in Oxfordshire. Wayland’s “smity” is in fact a long chambered barrow, a remnant of England’s early Neolithic period, and has been dated to roughly 3600 BC. This means that it most certainly has nothing to do with Wayland, except it bears his name. That name for the barrow is mentioned as early as 955 AD.

There are a lot of myths related to this barrow in the surrounding region that have been passed down through generations. The most common legend that all the villagers near the barrow know – even today – is that of an “invisible smith” who lives there. It is believed that any person who brings their horse in front of the barrow and leaves it there together with a coin, will return to find their horse with new horseshoes, expertly shod. It is also said that this fantastic smith will repair not only horseshoes, but any broken tools. One simply had to leave the tool and a sixpenny coin at the entrance, and upon returning the item would be mended.

Wayland’s Smithy, the long barrow in England linked to Wayland the Smith, dates from the Neolithic period but is named after Wayland all the same. (Ethan Doyle White / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Also known as the “ Wayland Smith’s Forge” this ancient, chambered barrow has almost become a pilgrimage site. All those who happen to visit it leave coins, sticking them between the stones and into small cracks. This practice is very old – based on ancient folkloric tales– and has been popularized since the 1960’s. This resulted in a great accumulation of coins, which are regularly removed by the authorities of English Heritage charity. Sadly, the origins of the folk story and how the barrow got its name are lost to time. However, it is widely agreed that the name was given by the Saxons, upon their arrival to the British isles.

Wayland’s Home: The Flying Men of The Island Of Borkum

Still, one question pops up as a real brain teaser. Can it be that the story of Wayland the Smith is far older than the Old Norse sagas? One notable feature of this story is the focus on the hamstring tendon as a point of weakness, much like in the Greek story of Achilles and his tendon. It also adds up to the story of lameness, found in many Indo-European smith gods. While Wayland is not specifically known as a god, it is quite likely that he was at some point worshipped as the god of blacksmiths and the forge.

There is also one particular custom that survives in Frisia (Germany), which can point to a much older tradition that is connected to Wayland’s myth. And that custom is almost exclusive to the East Frisian island of Borkum, which is less than 50 kilometers from Schweindorf, the village where the “Wayland coin” was discovered.

The Feast of Klaasohm “festival” is almost exclusive to the East Frisian island of Borkum, which is less than 50 kilometers from Schweindorf, the village where the “Wayland coin” was discovered. (G.Meyer / Copyrighted free use )

On this small island, men dress up every December 4 th. Their costumes are made from sheep skins, and they wear elaborate, large wings made from many bird feathers. The custom is known as the Feast of Klaasohm, and it consists of the men first going across the island “hunting” for women and scaring the folk. After they do this, they gather at the village center, where they “attempt to fly away” as if to escape. This is symbolically represented by simply jumping from a small elevation into the gathered crowd. Could Borkum be the mythical island on which Wayland was imprisoned by the cruel king? And could it be that this ancient myth survived to this day around the home of the storied hero?

Wayland’s Story: A Glimpse Into Europe’s Most Ancient Past

Rarely are the stories and heroes from Germanic mythology so widespread and backed up with deep evidence as is the story of Wayland the Smith. It spread through the Germanic world alongside its peoples, from Scandinavia, Frisia, Germany, and all the way to the British Isles.

And from then on, it has continued to provide a crucial insight into the beliefs and ancient legends of the Proto-Germanic tribes, and the Indo Europeans before them. Still, today, thousands of years later, we can only wonder whether the story of Wayland was based upon a real hero, or perhaps something even greater?

Top image: A closeup of one side of Franks Casket showing Wayland the Smith on the left side. Source: © Trustees of the British Museum / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References

Faber, H. 2019. Weladu the Flying Blacksmith. Frisia Coast Trail. [Online] Available at:

https://www.frisiacoasttrail.com/post/2019/11/16/weladu-the-flying-blacksmith

Mackley, J. S. 2011. A Forgotten God Remembered: The Wayland Smith Legend in Kenilworth and Puck of Pook’s Hill. The University of Northampton.

Olsen, K. and Harbus, A. and Hofstra, T. 2001. Germanic Texts and Latin Models: Medieval Reconstructions. Peeters Publishers.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 21st, 2020

November 21st, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: