When pondering themes of war and peace, there is a general perception among modern people of the Western world that the time we live in is decidedly more civilized and peaceful than any other era of human history. Most believe that modernity is characterized by the continued decline of violence in all its forms, with a decrease in public displays of brutality and an increase in inter-personal civility.

We collectively gasp in horror at the sight of medieval torture devices like the rack, or at the idea that crowds of people might go to see a heretic burned at the stake in the town square and consider it a form of entertainment. Even in the Early Modern period, with its Renaissance of art and culture, Europe is assumed to have been in an almost constant state of war.

The Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century brought about new philosophies and ideals of liberty, progress and tolerance that emphasized the ascendency of reason, and these philosophies began to change the nature of war and peace in European societies. However, that is not to say that pre-Enlightenment Europe was a cesspool of violence and chaos.

In fact, strong codes and rules have existed in Western societies for over a thousand years that governed practices of both war and peace. Despite the undeniable brutality and atrocities that occurred in the pre-modern era, it pales in comparison to the mass violence that has been perpetrated in the modern era and so begs the question: has our “enlightenment” really made us more civilized?

The coronation of Charlemagne marked a turning point in conceptions of war and peace in Europe. ( Public domain )

The Laws of War and Peace

Since the reign of Emperor Constantine in the 4th century, the idea of a Christian Empire prevailed in the European political consciousness. The concept of peace became infused with Christian notions of morality and righteousness. Violence was recognized as necessary in order to achieve that peace, though it was to be exercised in a controlled manner for the sake of social order. The ultimate realization of the unity between empire and Christianity came in the year 800, with the crowning of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor at St Peter’s Basilica in Rome on the 25th of December.

Charlemagne’s coronation marked a turning point, bringing a sense of cultural unity to Western Europe which encouraged the nations of Western Christendom to see themselves as more civilized because of their religion and to seek peace within Europe. That is not to say that all wars suddenly ceased overnight and Europe was at peace, but rather peace became a theological ideal.

The aim was for God’s divine peace in heaven to be mirrored on Earth in a civil concord that, although evading permanent residence in human society, could be temporarily attained through ethical and political structures that were violently enforced when necessary. These ethical structures, the so-called “Laws of War”, became very clearly defined in the medieval era and would define the terms of conflict right up until, and even into, the modern era.

The Laws of War in Western Christendom rested upon five ideological pillars: Roman law, Canon law as set down by Church Fathers like Gratian, the writings of St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas, and of course the Bible. The critical passage of scripture that governed European practices of war was Deuteronomy 20:10-20:

“When you march up to attack a city, make its people an offer of peace. If they accept and open their gates, all the people in it shall be subject to forced labor and shall work for you. If they refuse to make peace and they engage you in battle, lay siege to that city. When the Lord your God delivers it into your hand, put to the sword all the men in it. As for the women, the children, the livestock and everything else in the city, you may take these as plunder for yourselves .”

In this passage can be found the basis for the general customs of war followed by armies on the battlefield. Preservation of the lives of women and children, restraint from deliberate or ostentatious cruelty, the taking of plunder in siege warfare , all of which were reinforced in the 11th and 12th centuries by the Chivalric Code to which knights were expected to adhere, as well as the Peace of God movement, which dictated that the weak should not be harmed, and the Truce of God, which forbade armed conflict on certain days of the week and during important religious festivals.

What is important about this passage in Deuteronomy is that it also dictates the Laws of War should not apply to non-Christian opponents, because “otherwise, they will teach you to follow all the detestable things they do in worshiping their gods, and you will sin against the Lord your God.” Unfortunately for the Celts, Turks, and other non-Christian peoples of Europe, this ideology encouraged Christian societies to make war upon them in the name of enforcing Christian imperial peace, and was justified by characterizing non-Christians as murderous barbarians who made wars upon each other.

In these trans-cultural wars, higher levels of brutality and atrocities were often enacted because the Laws of War were seen to only apply between equals, governing “the conduct of men who fought to settle by arms quarrels which were in nature private, and whose importance was judged by the social status of the principals involved.” It wasn’t until the 16th century that the Laws of War began to apply to all combatants, and even then only within continental Europe.

Pitched battles were rare in the medieval period and smaller skirmishes or raids were the standard practice. ( zef art / Adobe Stock)

The “State” of Pre-Modern Warfare

Warfare in the medieval and Early Modern periods was not as it has often been represented in Hollywood films, with hundreds or thousands of armored men and horses valiantly charging across an open field to hack at each other with broadswords until only one side remained standing to claim victory. In reality, pitched battles were rare in the medieval period and smaller skirmishes or raids were the standard practice. Conflict between kingdoms or nations was usually small-scale, sporadic, ritualistic and highly disorganized, with minimal casualties.

It was not uncommon for combatants to be peasants and farmers, clad in simple leather armor and carrying spears or pikes – only knights received formal training in the arts of war and possessed the means to acquire proper metal armor, horses, and swords. State-funded standing armies were not developed until the Early Modern period, but even then siege warfare remained the crucial strategy in warfare and pitched battles were uncommon. Hunger and disease were by far the biggest killers during Early Modern warfare, more so than any weapon including bullets after the discovery of gunpowder.

The nature of medieval warfare meant that civilian casualties and brutality against non-combatants was the normal currency of war. The typical mode of battle was to raid civilian communities in enemy territory to damage economic capacity and undermine morale of the people, either with the intention of forcing the attacked ruler to act or to terrorize non-combatants into changing allegiance if unprotected by their overlord. Brutality is inevitable in the heat of war, and atrocities were commonplace despite the Laws of War and other codes of conduct based on custom and convention.

In the chronicle of Thomas Walsingham, he writes that during a Scottish raid on a Northern English town in 1379 the Scots decapitated local men and then played football with the severed heads. Similar atrocities were committed centuries later, when Oliver Cromwell’s army sacked the Irish town of Drogheda in 1649 and his army slaughtered both surrendered captives and non-combatants (including priests) without discrimination – the governor Sir Arthur Aston is said to have had his brains beaten out with his own wooden leg and what was left of his head sent to Dublin on a pole.

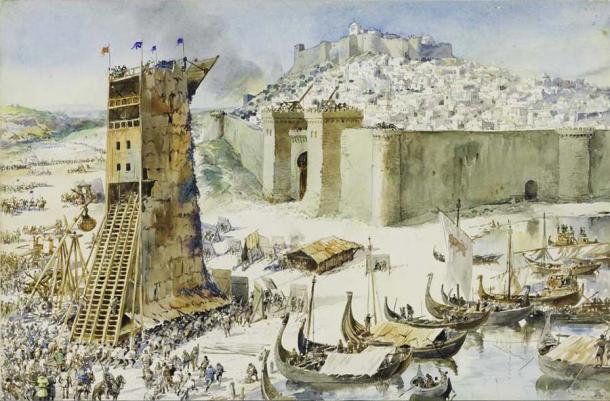

The Siege of Lisbon in 1147 by Roque Gameiro. ( Public domain )

Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Although restraints were loosened somewhat in siege warfare – a sacking was treated as “total war” and resisting surrender disentitled the vanquished to any quarter – some acts of violence were generally frowned upon among Western Christian societies. The killing of women and children (particularly virgins, infants, or the elderly) and clerics was considered despicable, and sexual molestation of women or spoliation of churches was widely condemned.

Such distinctions may seem arbitrary, and arguably any act of brutality committed in war is un-Christian no matter the victim’s identity, but pre-Modern Europeans did not recognize these martial attitudes as being against their religion but rather in line with it. Most Europeans saw God as inherently violent, contrary to the modern view of Christ as a pacifist, and so long as violent acts were committed in the name of a just cause then brutality was considered legitimate.

Even extreme brutality and excessive cruelty could be viewed as necessary when enacted for a “just” cause: pre-Enlightenment Europe relied on violence as one of the principal social mechanisms for maintaining social hierarchies. Non-Christians were seen as a threat to the integrity of the community, with those who could not be converted seen as resisting unjustly and undeserving of mercy.

Similarly, in Pre-Modern feudal societies, those who challenged status boundaries – such as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in England – were a threat to social order and therefore met with prompt, severe, and inflexible punishment. The codes of chivalry governing conduct during war did not apply to those of lesser social standing, and so the military classes thought of their social inferiors and non-Christians as little more than animals and therefore subject to a different set of morals.

In wars fought between parties of more equal footing, both of whom subscribed to the prevailing martial ideals of Western Christendom, a framework of expectations and etiquette developed as combatants came to realize the advantages of mutual restraint – like honoring surrender, sparing wounded and respecting flags of truce – to reduce the danger and chaos of conflict.

Acts of brutality tended to be more symbolic, such as King Edward I publicly executing male aristocratic enemies in the Anglo-Scottish Wars, while female aristocrats were put in cages and publicly shamed instead of murdered. The Scots showed reciprocal strategic restraint in treatment of prisoners, choosing to amputate the hands of captured English archers, who were the biggest military threat to Scottish victory, and sending them home to act as a deterrent to others who would fight against the Scots.

Mass grave at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp taken in 1945. ( Public domain )

Peace in Our Time

As the Early Modern period progressed and the power of European states grew, standing armies developed and military personnel were provided by their governments with regular pay and supplies such as food and clothing. Although the Reformation had weakened the protections created by religious unity that had existed since the early Middle Ages, treatment of civilians in conflict was generally more restrained as armies no longer needed to plunder in order to survive.

In the latter part of the period, individual soldiers also began to be held accountable for acts of excessive force and the concept of war crimes began to develop. Military tribunals were held to discipline combatants who had committed offences that were contrary to the Laws of War, which were largely unchanged since the Middle Ages, and punishments for transgressions could be extremely harsh, including the death penalty.

The dream of a peaceful Christian Empire imagined by Constantine and Charlemagne had been somewhat realized by the mid-17th century. Religious frontiers had mostly stabilized by this time and the Peace of Westphalia treaty signed in 1648 signified a desire among European states to end wars fought over religious differences, so the Modern era was ushered in among relative peace. Enlightenment philosophers wrote treatises on the nature of peace, including Immanuel Kant’s Perpetual Peace :

“States find themselves compelled to promote the noble cause of peace…and wherever in the world there is a threat of war breaking out, they will try to prevent it by mediation, just as if they had entered into a permanent league for this purpose… In this way, nature guarantees perpetual peace by the actual mechanism of human inclinations.”

While modern ideals are all well and good however, we now know that whatever peace and unity Europe had found in the Age of Enlightenment was to be only temporary. Contrary to what Enlightenment philosophers envisioned, the modern era was to be characterized not by a decrease in violence, but an increase. The uptake of state-controlled violence escalated the level of brutality humanity would witness in some of the largest, bloodiest wars in history.

From the mass casualties of the Great War to the genocide witnessed during the Holocaust, the modern era has seen the execution of atrocities worse than any ever recorded throughout human history. Despite our perception of the modern world as more peaceful and civilized than in bygone eras, our era has seen destruction on such a scale that no pre-modern society had the organizational, technological or ideological means to achieve, and so we might ask ourselves: with all our enlightened ideals, are we really more civilized than our ancestors?

Top image: Are our conceptions of war and peace more civilized in modern times? The Apotheosis of War, by Vasily Vereshchagin. Source: Public domain

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Bellis, Joanna, and Laura Slater, eds. 2016. Representing War and Violence: 1250-1600 . Boydell & Brewer.

Macdonald, Alastair J. 2018. “Two kinds of war? Brutality and atrocity in later Medieval Scotland.” In Killing and Being Killed: Bodies in Battle-Perspectives on Fighters in the Middle Ages , ed. Rogge, Jörg. Verlag.

Malešević, Siniša. 2013. “Forms of brutality: Towards a historical sociology of violence.” European Journal of Social Theory 16, no. 3.

Parker, Geoffrey. 2002. Empire, war and faith in early modern Europe . Allan Lane.

Reichberg, Gregory M., Hendrik Syse, Endre Begby, eds. 2006. The Ethics of War: Classic and Contemporary Readings . Blackwell Publishing

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 16th, 2021

October 16th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: