Between The Pastoral and The Sublime

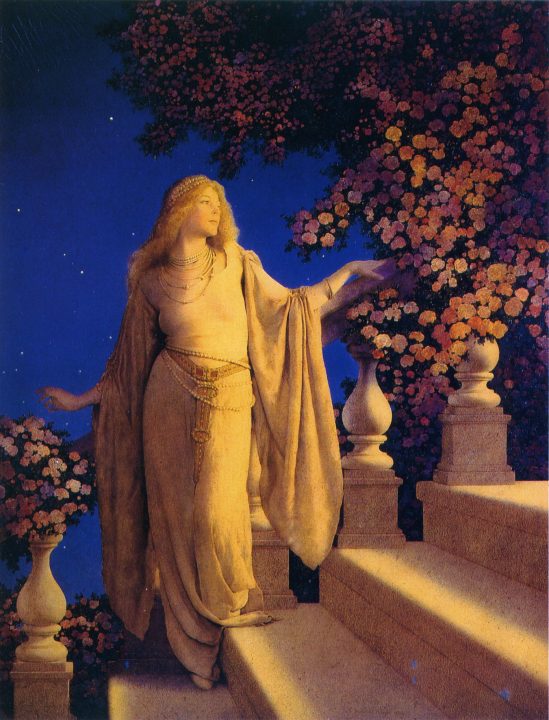

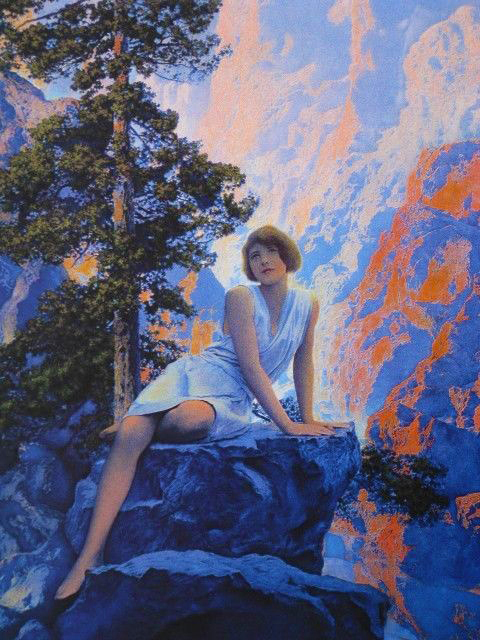

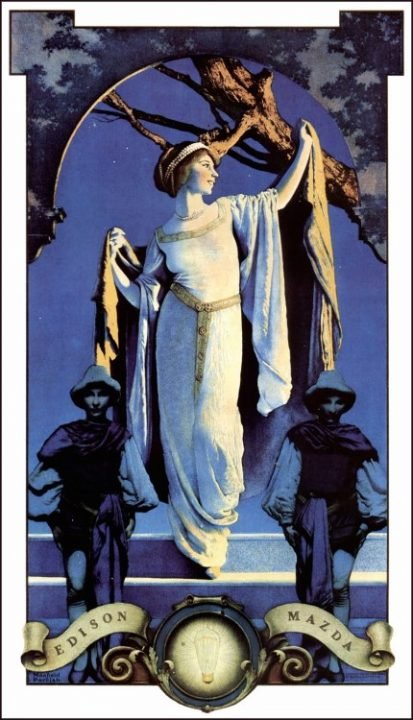

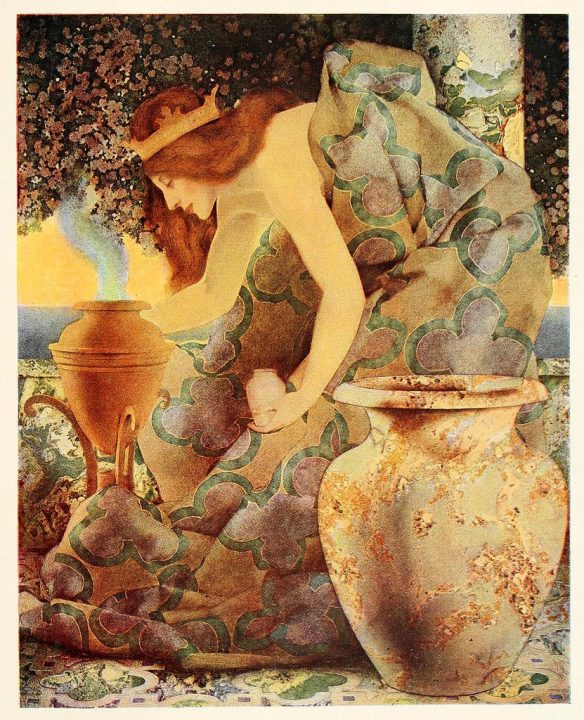

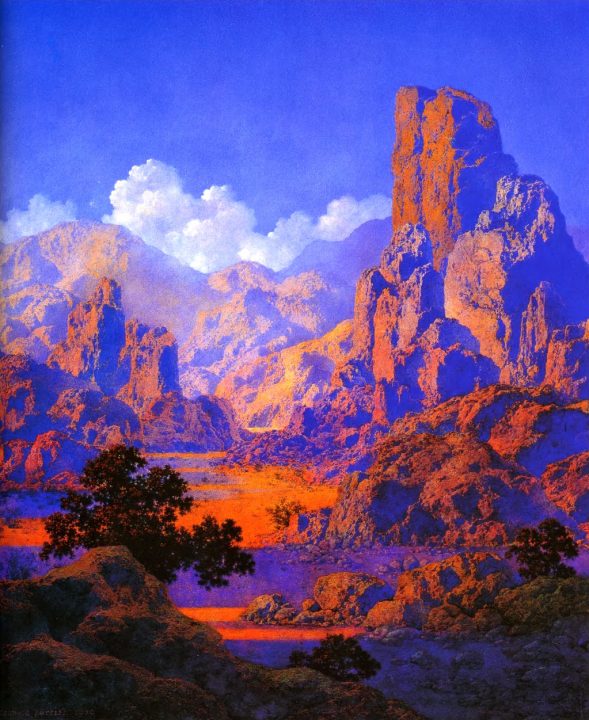

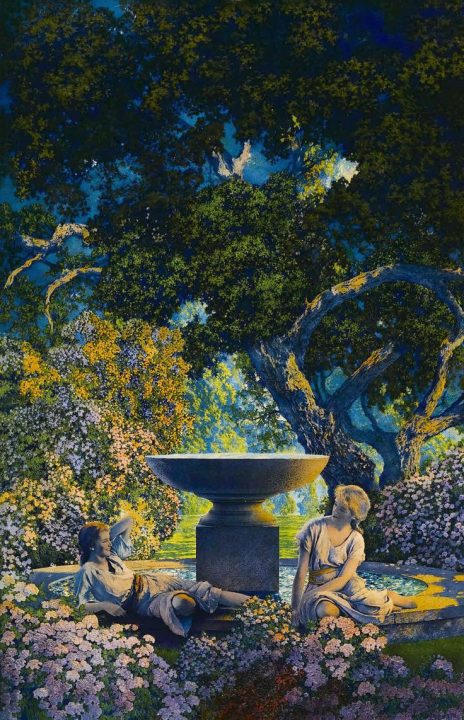

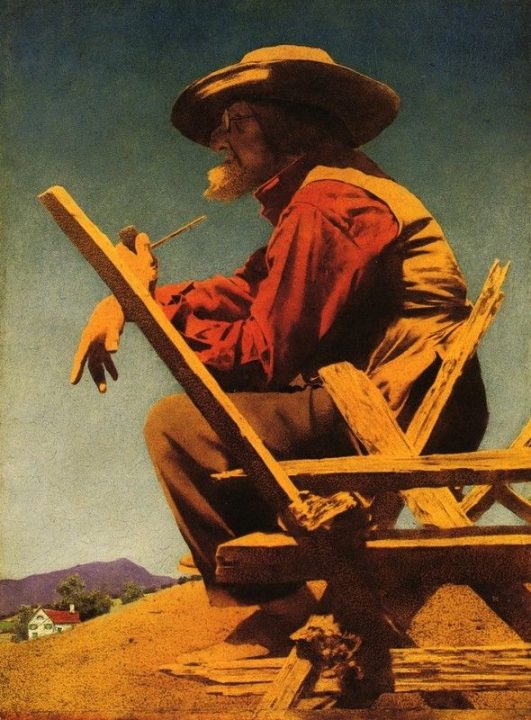

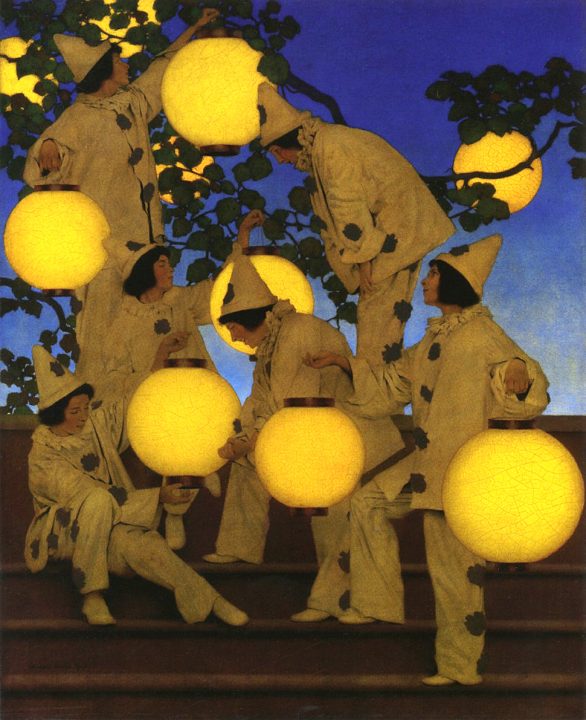

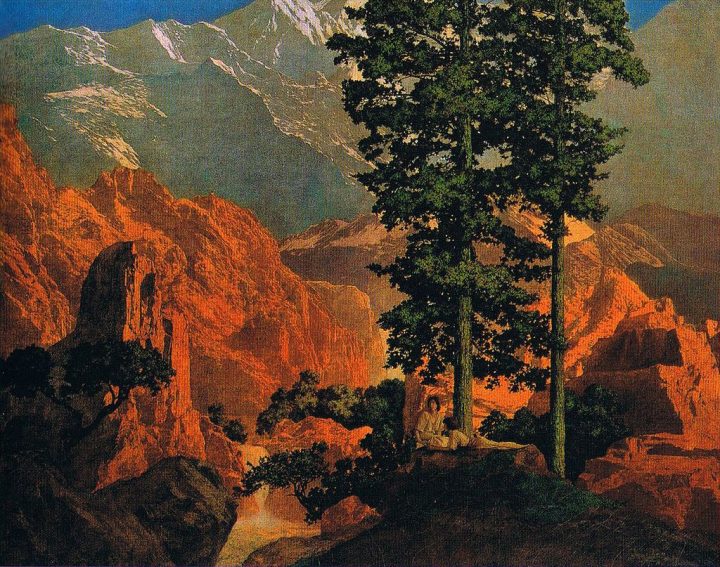

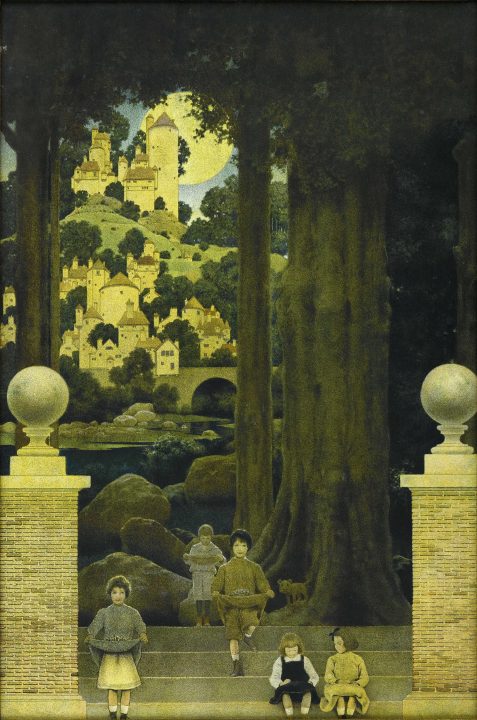

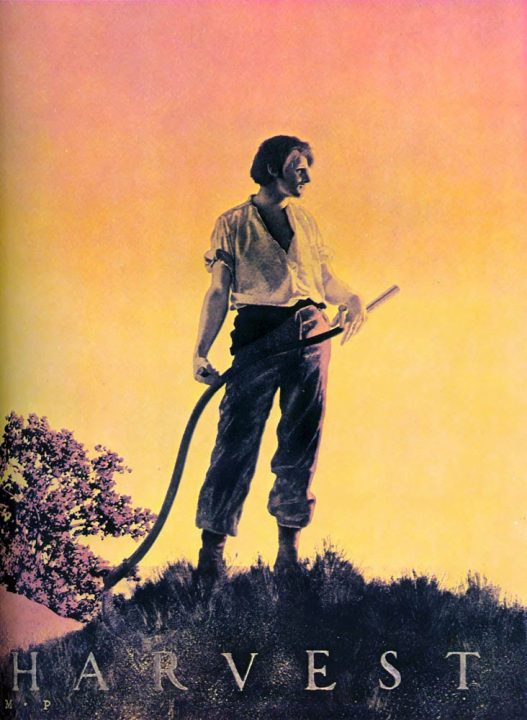

According to Merrian-Webster’s dictionary the definition for oneiric corresponds to ‘of or relating to dreams’, that is exactly my first thought when looking at many paintings by American born artist Maxfield Parrish. In spite of Parrish being an incredibly successful artist (commercially-wise) during his long career he was able to project a very personal vision of the reality he saw via his artistic perception in many of the pastoral paintings he created. Many of Parrish’s works of art became part of certain collective vision. In my opinion he understood perfectly well the evocative power of light and shadow during waking and sunset hours and the emotional effect this can have on the beholder. His classical illustrations of sun-gazing young ladies sporting 1920’s styled haircuts and clad, in what it seems to be, classical thin robes, are a prime example of this tendency which (unfortunately) he got a bit tired of exploiting at some point.

I’m done with girls on rocks! I’ve painted them for thirteen years and I could paint them and sell them for thirteen more. That’s the peril of the commercial art game. It tempts a man to repeat himself. It’s an awful thing to get to be a rubber stamp. I’m quitting my rut now while I’m still able.” – Maxfield Parrish

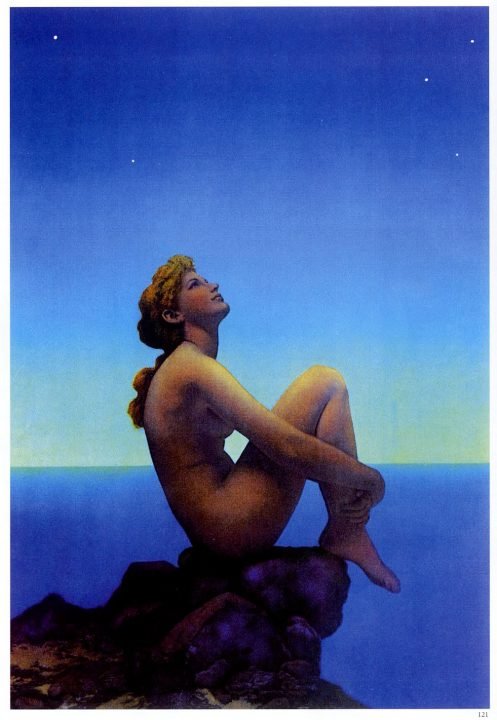

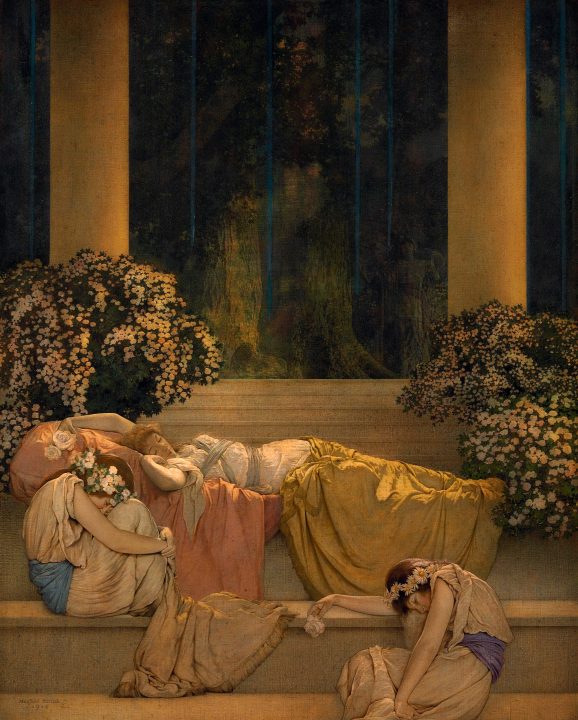

Parrish’s representation of the bucolic paradisaical world of dreams and visions is best encapsulated in his masterpiece Daybreak (1922) a painting executed specifically for massive reprint. Parrish was probably inspired by New Hampshire’s natural scenery, which was quite close to his heart, to create this lush, romantic painting. So huge was the success of this art piece that it became the most successful art print of the 20th century. Based on number of prints made the estimation was that one out of every four American homes had one copy hanging on a wall. According to The National Museum of American Illustration, Daybreak has outsold Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans and Da Vinci’s Last Supper. The painting is obviously still in print. However Daybreak became part of a private collection very early on. On May 25, 2006, Daybreak was purchased by Mel Gibson’s then-wife, Robyn at auction at Christie’s for US $7.6 million. This set a record price for a Parrish’s painting (and I suppose for ANY painting at any auction). It was sold again on May 21, 2010 this time for US $5.2 million.

Such was the evocative aura of Daybreak that it became a source of inspiration for all sorts of musical artists, so much so that this particular image has been used and revamped innumerable times for record covers and other promotional media: The Moody Blues album The Present uses a variation of Daybreak for its cover. In 1984, Dali’s Car, the British New Wave project of Peter Murphy and Mick Karn, used Daybreak as the cover art for their only album, The Waking Hour. The Irish musician Enya has been inspired by the works of Parrish quite consistently. The cover art of her 1995 album The Memory of Trees is based on Parrish’s painting The Young King of the Black Isles (1906). A number of her music videos include Parrish imagery, including Caribbean Blue. In 1995 Michael Jackson produced a music video, You Are Not Alone, featuring himself and his then wife, Lisa Marie Presley, in which they appear semi-nude in emulation of Daybreak. A 1986 Nestle television commercial for Alpine White features one scene imitating Daybreak and another resembling Parrish’s Ecstasy (1929). The Saint Preux album The Last Opera also uses Daybreak for its cover. The Elton John album Caribou had a background inspired by Parrish’s works.

Parrish was criticized by some people for the representation of some characters in his paintings which looked somewhat androgynous. I attribute this to the fact that Parrish always used his favorite model and lifelong ‘companion’, Susan Lewin (a young girl who he first employed as a household assistant to his wife, Lydia) as the main character for many of his paintings. I suppose this was done in the same way that many voice-overs of little boy characters in cartoon movies these days are actually done by women (Unless there was/is some kind of sinister agenda behind it all. That would be an interesting subject to discuss).

Biography

Born Frederick Parrish in Philadelphia in 1870, the only child of Stephen Parrish (a reputed artist himself) and Elizabeth Bancroft Parrish, he was raised in a well-to-do home with many comforts. His father became a well-known etcher in his own right and fully encouraged the young Fred to draw and paint. Parrish suffered from tuberculosis for a time in 1890. While sick, he discovered how to mix oils and glazes to create vibrant colors.

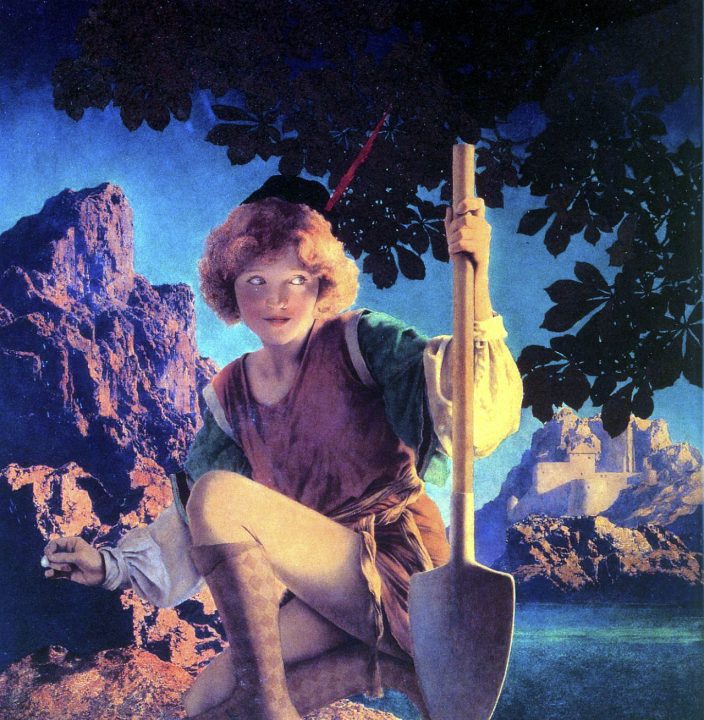

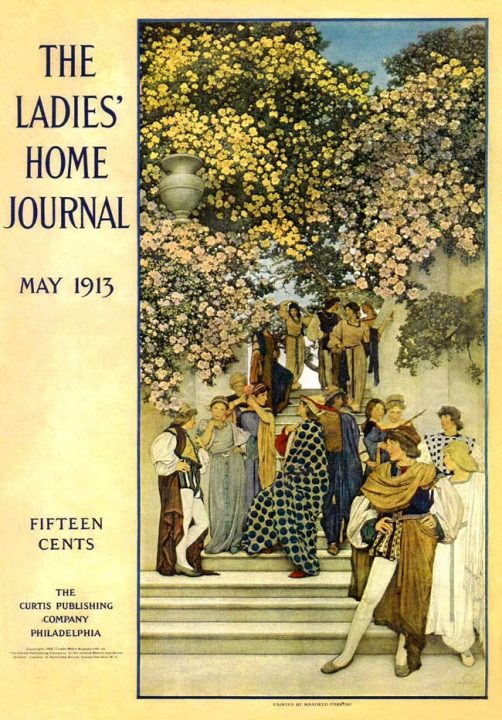

Frederick later took his grandmother’s maiden name as his middle name, which he used as his professional name from then on. He graduated Haverford College and then attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Art, and the Drexel Institute, where he took classes with Howard Pyle, who recommended him for his first cover commission. At Drexel, Parrish met a young art instructor, Lydia Austin, who he married in 1895. By 1911, the couple had four children (Dillwyn, Max Jr., Stephen, and Jean). Throughout the first part of the 20 th century, Parrish did many commissions and illustrations. His paintings featured fanciful male figures or pensive female figures in the foreground of a fantastic landscape.

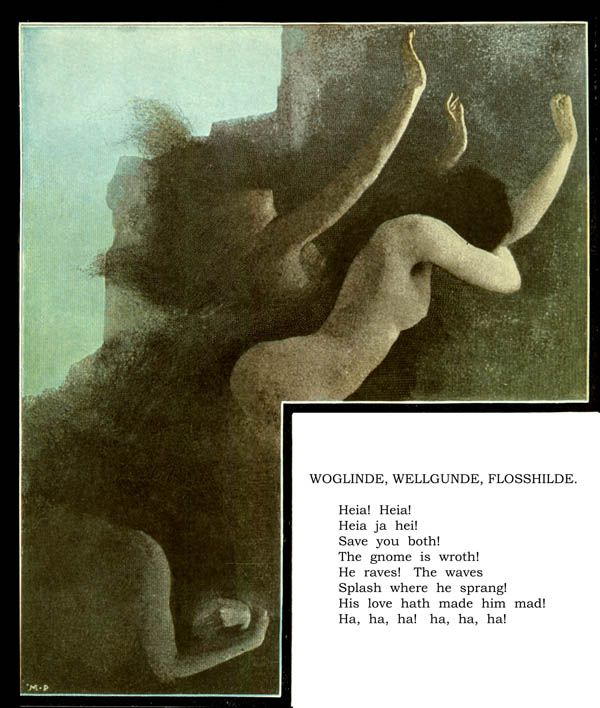

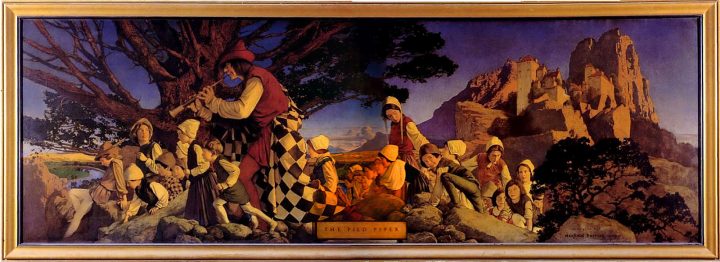

Parrish took many commissions for commercial art until the 1920s. Among these works were included many prestigious projects such as Eugene Field’s Poems of Childhood (1904), and traditional works as Arabian Nights in 1909. Books illustrated by Parrish are featured in A Wonder Book and Tanglewood Tales in 1910, The Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics in 1911, and The Knave of Hearts in 1925. He even illustrated his own version of Das Rheingold in 1898 in the early days of his career. By 1931, however, he had decided he was through with figurative painting and devoted the rest of his life exclusively to landscape painting.

Always keenly aware of the commercial value of his artwork, Parrish entered a new phase of his career in 1935, painting landscapes for the calendar publisher, Brown and Bigelow, which continued until 1962. During those years, they printed more than 50 of his landscapes, although by the 1950s, public interest in his work had seriously waned. His wife, Lydia, died in 1953, and despite having been with Susan Lewin for four decades, he did not marry her. In 1960, at the age of 70, she married a local man she had known since childhood, although she still continued to tend to Parrish, cooking meals and assisting him in his studio.

Maxfield Parrish enjoyed two periods; book-ending the beginning of his career in the early 1900s through the 20s, and later in the 1960s when his work was immensely popular, he was often dismissed by critics as a second-rate artist who was mainly an illustrator. He painted his last picture at the age of 91, a landscape called Getting Away From it All (1961).

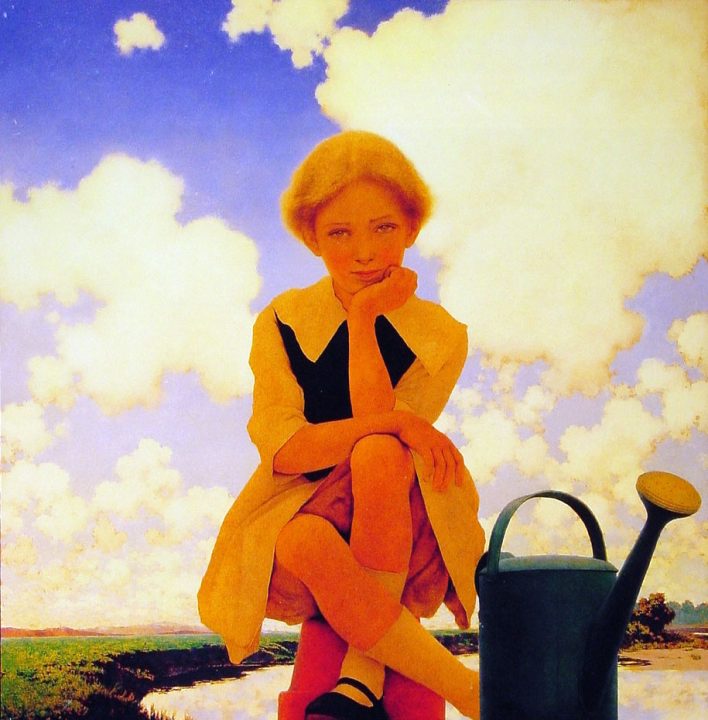

Parrish’s youngest child, Jean, posed for Ecstasy (1929) just before leaving for Smith College. Jean was the only child to follow her parents’ profession

In 1964, two years before his death, a retrospective of his work shown at Bennington College in Vermont helped to establish the notion of Parrish as a major contemporary American artist. The show was organized by abstract painter Paul Freeley and then-curator of the Guggenheim Museum, Lawrence Alloway, who felt his work had strongly influenced the emerging “pop art” movement. By all accounts, the best known pop artist of all time, Andy Warhol, had collected many of Parrish’s works. When the show traveled to the Gallery of Modern Art in New York, the ensuring reviews sparked a major revival of interest in Parrish’s work. That same year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased the painting, The Errant Pan signaling his arrival as a major artist.

Parrish died on March 30, 1966 in Plainfield, New Hampshire, at the age of 95. As a final word on the scope of fame Parrish achieved the words by famous American painter Norman Rockwell should suffice when he referred to Parrish as ‘my idol’. That should say a lot on Parrish’s behalf.

Sources

– How Maxfield Parrish Got So Blue (January 18, 2010) by Arts Enclave’s Blog – most biographical notes are taken from this excellent article.

– Our American History by Nell Porter Brown (Published Summer 2015) Harvard Magazine

– Maxfield Parrish Artworks by The Athenaeum

– Maxfield Parrish Wikipedia

– Maxfield Parrish Wikiquote

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/visions-paradise-oneiric-worlds-maxfield-parrish/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 26th, 2017

July 26th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: