Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, is disintegrating at an incredible pace under the country’s political and economic crisis that has left citizens broke, desperate and in many cases, homicidal. The depreciation accelerated this week, after a disputed vote electing an all-powerful “Constituent Assembly” filled with allies of President Nicolas Maduro, which the opposition and dozens of countries have called illegitimate.

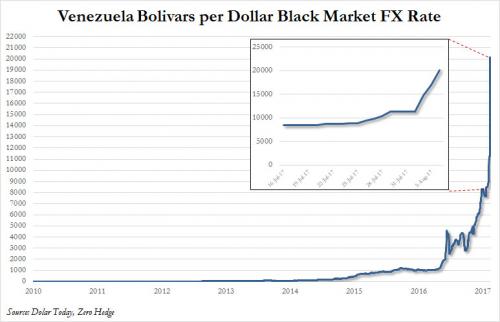

Just two days ago, on August 2, we reported that one dollar would buy 14,100 bolivars, up from 11,280 the day before.

The next day, the bolivar slumped nearly 15 percent on the black market, to 17,000 to one US dollar. Today, it has crashed again, tumbling 16% to 20,142, and down almost 40% in just the past three days.

In the past year, the currency increasingly looks like shares of DryShips, having lost over 96% while the longer-term chart is simply breathtaking.

The decline, in France24’s words, has been “dizzying” yet completely largely ignored by the government, which continues to use an official rate fixed weekly that is currently 2,870 to the dollar, and which is completely useless. Meanwhile, ordinary Venezuelans refer only to the black market rate they have access to, which they call the “dolar negro,” or “black dollar.”

“Every time the black dollar goes up, you’re poorer,” resignedly said Juan Zabala, an executive in a reinsurance business in Caracas. His salary is 800,000 bolivares per month. On Thursday, that was worth $47 at the parallel rate. A year ago, it was $200. The inexorable dive of the money was one of the most-discussed signs of the “uncertainty” created by the appointment of the Constituent Assembly, which starts work Friday.

As a result, those Venezuelans who are able to are hoarding dollars and other currency alternatives.

“People are protecting the little they have left,” an economics expert, Asdrubal Oliveros of the Ecoanalitica firm, told AFP.

Zabala — who is considered comparatively well-off — and other Venezuelans struggling with their evaporating money said they now spent all they earned on food. A kilo (two pounds) of rice, for instance, cost 17,000 bolivares. The crisis biting into Venezuela since 2014 came from a slide in the global prices for oil — exports of which account for 96 percent of its revenues.

The government has sought to monopolize dollars in the country through strict currency controls that have been in place for the past 14 years. Access to them have become restricted for the private sector, with the consequence that food, medicines and basic items — all imported — have become scarce.

According to the International Monetary Fund, inflation in Venezuela is expected to soar above 700 percent this year. In June, Maduro tried to clamp down on the black market trade in dollars through auctions of greenbacks at the weekly fixed rate, known as Dicom. There is also another official rate, of 10 bolivars per dollar, reserved for food and medicine imports.

“Things are going up in price faster than salaries,” noted Zabala, who spends 10 percent of his income on diabetes treatment, when he can.

Meanwhile, Maduro who earlier this week was branded a “dictator” by the US State Department, has vowed that a new constitution the Constituent Assembly is tasked with writing will wean Venezuela off its oil dependency and restart industry, which is operating at only 30 percent of capacity. But Maduro, who links the “black dollar” with an “economic war” allegedly waged by the opposition in collaboration with the US, has not given details on what would be implemented. Instead, on Thursday Maduro promised that “speculators” setting their prices in line with “the terrorist criminal dollar in Miami” would go to jail.

Against that backdrop of tensions, “there is no limit on how far the black dollar can go,” according to Ecoanalitica.

But a director of the firm, Henkel Garcia said he believed the current black market rate “didn’t make sense” and he noted that in the past currency declines weren’t linear.

Oliveros said increased printing of bolivares by the government was partly the reason for the black dollar’s rise. “When you inject bolivares into the market, that means that companies, individuals go looking for dollars, which are scarce,” he said, estimating that the shortfall of dollars this year was some $11 billion.

And as Latin America’s socialist paradise succumbs to Venezuela, it has further headaches ahead: Venezuela has to make major debt payments, with a $3.4 billion dollar-denominated payment for state oil company PDVSA looming in October. It is increasingly unclear if the company will make the payment.

Source Article from http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/blacklistednews/hKxa/~3/cOkZZWA70Rk/M.html

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 5th, 2017

August 5th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: