An investigation into how U.S. Special Forces trained feared Mexican drug cartels responsible for grisly murders, and how Pentagon-backed counter-insurgency in Colombia and Guatemala has bled into organized crime.

(This article was first published in CovertAction Magazine.)

The Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) has established itself as one of the most feared paramilitaries in Mexico over the last decade. Images of the group have become the standard depiction of the Mexican cartels writ large. Their propaganda videos often feature groups of masked men bristling with enough small arms to make them formidable against even conventional armies.

In an interview aired on Mexico’s Telemundo network in May 2019, a former CJNG soldier described his experience at a training camp and claimed that the cartel employed U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF) to train their recruits.

According to the former sicario (assassin), there was “a group of elite Marines, there were [members] of the United States Navy, there were Delta Forces, there was everything there.”

The cartel dropout’s account is consistent with years of reports which show that U.S. Special Forces training is diffusing into the service of paramilitaries in Mexico.

The Special Forces training has been funded under the Plan Mérida, which has resulted in the U.S. providing more than $1.6 billion for fighting the War on Drugs, most of it in military aid.

In 2019, after a U.S. ex-pat family was killed by drug cartel gunmen, then-President Donald Trump tweeted that now was “the time for Mexico, with the help of the United States to wage WAR on the drug cartels and wipe them off the face of the earth.”

However, the goal of defeating the cartels is undermined when U.S. Special Forces soldiers are actually assisting their enemy, and training drug cartels that commit horrific atrocities.

A frame from Mexico’s Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) video ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-Cartel-Jalisco-Nueva-Generacion-CJNG-video.jpg?fit=300%2C180&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-Cartel-Jalisco-Nueva-Generacion-CJNG-video.jpg?fit=1024%2C616&ssl=1″ />

A frame from Mexico’s Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) video ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-Cartel-Jalisco-Nueva-Generacion-CJNG-video.jpg?fit=300%2C180&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-Cartel-Jalisco-Nueva-Generacion-CJNG-video.jpg?fit=1024%2C616&ssl=1″ />Mexico’s Los Zetas cartel trained by U.S. military forces

The most well-known example of U.S. training disseminating into the wrong hands has been Los Zetas.

The Zetas were enforcers for the Gulf cartel, which recruited deserters from Mexico’s Airborne Special Forces Group (GAFE). Formed in 1986 as an elite quick reaction force specializing in counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare, the GAFEs received their first combat experience in the brutal fight with the leftist Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in Chiapas, when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect in 1994.

According to reporting by Mexican journalist Carlos Marin, the army deployed the GAFEs in Chiapas to create paramilitaries and displace the population in order to disrupt the support of the people in the area for the EZLN – a counterinsurgency approach which would later be used against organized crime.

In reporter Ioan Grillo’s book El Narco, he describes how the mutilated bodies of rebels captured by the GAFES were dumped along a riverbank with their ears and noses sliced off, the sort of spectacular exhibitions of violence for which the Zetas would later be known.

Some of the original members of the Zetas were reportedly trained by the U.S. at the notorious School of the Americas, although conflicting accounts exist about exactly who, where, and when, with some sources like the FBI claiming they were trained at Fort Benning, and others like a former Special Forces commander claiming the GAFEs trained with the Army’s Green Berets at Fort Bragg.

A classified 2009 memo from the U.S. State Department published by WikiLeaks claimed that their own incomplete official records found that none of the known Zetas had ever participated in U.S.-funded training programs using their real names, but acknowledged that other intelligence sources indicated that one former Mexican military officer trained in the U.S. was forcibly recruited by the Zetas.

Members of the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Los-Zetas-Mexico-cartel.jpg?fit=300%2C183&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Los-Zetas-Mexico-cartel.jpg?fit=1024%2C624&ssl=1″ />

Members of the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Los-Zetas-Mexico-cartel.jpg?fit=300%2C183&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Los-Zetas-Mexico-cartel.jpg?fit=1024%2C624&ssl=1″ />According to a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, Craig Deare, it was likely that more than 500 GAFEs trained in the U.S. with the 7th Special Forces Group (SFG), nicknamed the “snake-eaters.”

Deare served as the former academic dean at the Pentagon’s Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies, the intellectual center of gravity of U.S. defense policy in Latin America since 1997.

Deare, who previously commanded U.S. Special Forces, told Al Jazeera, “I had some visibility on what was happening, because this [issue] was related to things I was doing in the Pentagon in the 1990s.” He said the GAFEs “were given map reading courses, communications, standard special forces training, light to heavy weapons, machine guns and automatic weapons.”

The 7th SFG specializes in the approach the U.S. has taken with Latin America since the end of the Second World War: unconventional warfare, counterinsurgency and, more recently, counterterrorism.

During the Reagan administration in the 1980s, the 7th SFG trained, advised, and fought with some of the most brutal and repressive special operations and unconventional forces in Latin America, in countries such as Bolivia, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela.

Between 1996 and 1999, 3,200 soldiers, including at least 500 GAFEs, were reportedly trained by the 7th SFG in “counternarcotics” for fighting on behalf of the post-Cold War U.S. national security agenda.

In what is often framed as an ironic consequence of the corrupting influence of the cartels, the training from the U.S. and Mexican special forces diffused into the service of one of Mexico’s oldest drug-trafficking organizations, the Gulf cartel.

In 1997 – the same year as the inception of the Pentagon’s Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies – Arturo Guzmán Decena, a GAFE better known by the alias “El Zeta-uno” (Z-1), defected along with other members of Mexico’s Airborne Special Forces Group to work for Gulf cartel boss Osiel Cárdenas Guillen.

Trained and experienced in counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare before being repurposed supposedly to fight drug-trafficking, former GAFEs would become one of the most infamous and brutal drug-trafficking organizations in history: Los Zetas.

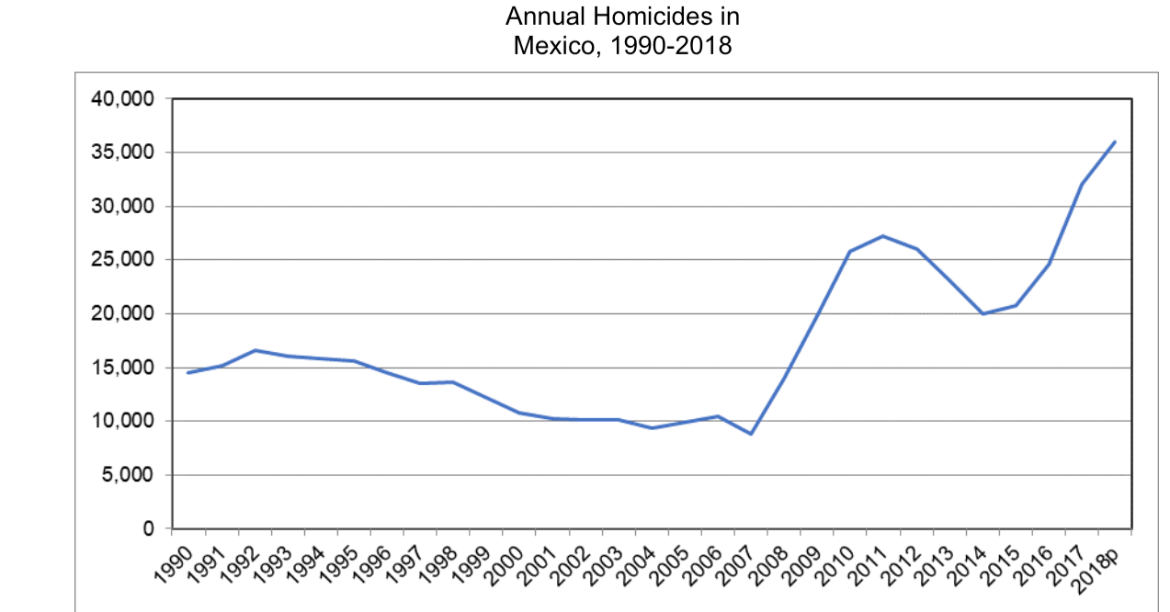

The Zetas’ advanced training and application of military tactics were used to justify Mexican President Felipe Calderón’s decision to deploy the military to prosecute the war against drug-trafficking in his first month in office, in 2006.

The consequences of that decision have been devastating for Mexico, leading to at least 100,000 deaths.

Mexico homicides graph

Mexico homicides graph

” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-homicides-graph.png?fit=300%2C157&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Mexico-homicides-graph.png?fit=1024%2C535&ssl=1″ />

Murderous Guatemalan special forces trained at Pentagon’s WHINSEC

According to a 2009 DEA memo, the Zetas also recruited other U.S.-trained Latin American special forces, like the Guatemalan Kaibiles.

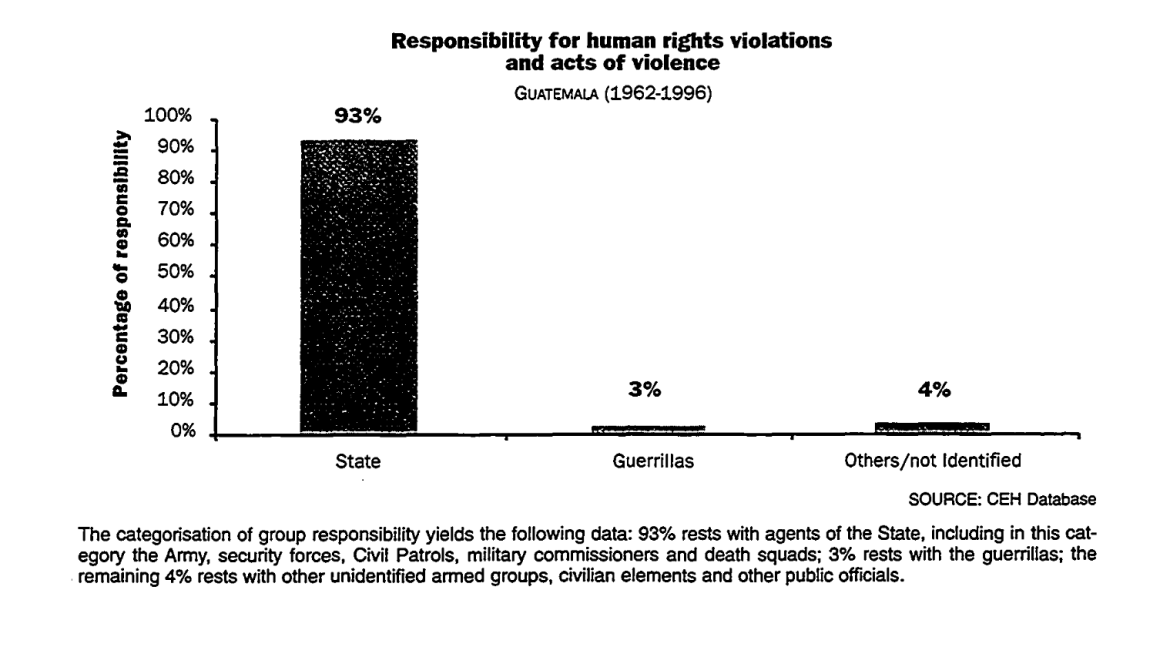

The Kaibiles and other security forces were trained by the U.S. in counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare before, during, and after Guatemala’s 36-year genocide.

After a 1999 report commissioned by the United Nations determined that the more than 200,000 people killed and disappeared by the Guatemalan Army constituted a genocide, the School of the Americas briefly closed, before reopening a year later under a new name: the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC).

According to testimony from a former instructor at the school, the changes were only superficial, and an identical curriculum was taught from the same instruction manuals.

The UN-backed commission’s official statistics on human rights violations committed during the Guatemalan Civil War ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/UN-Commission-Guatemala-human-rights-violations-state-guerillas.png?fit=300%2C166&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/UN-Commission-Guatemala-human-rights-violations-state-guerillas.png?fit=1024%2C566&ssl=1″ />

The UN-backed commission’s official statistics on human rights violations committed during the Guatemalan Civil War ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/UN-Commission-Guatemala-human-rights-violations-state-guerillas.png?fit=300%2C166&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/UN-Commission-Guatemala-human-rights-violations-state-guerillas.png?fit=1024%2C566&ssl=1″ />Between 1999 and 2010, 3,555 Guatemalan soldiers, many of them Kaibiles, were trained by the U.S. through WHINSEC and other programs.

In training, the Kaibiles learn to kill without mercy or thought. Recruits are reportedly given a puppy to look after and bond with for several weeks before they are ordered to kill the animal with their bare hands and consume the blood and flesh, a method which has since diffused to the Mexican GAFEs that train with the Kaibiles.

Like the 7th SFG “snake-eaters,” the Kaibiles are sustained by killing. Their motto is: “Si avanzo, sígueme. Si me detengo, aprémiame. Si retrocedo, mátame!” (“If I advance, follow me. If I stop, urge me on. If I retreat, kill me!”)

U.S. Marines training with Guatemalan “Kaibil” special forces in Poptun, Guatemala in 2010 (Photo credit: public domain) ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-military-special-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=300%2C168&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-military-special-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=1000%2C560&ssl=1″ />

U.S. Marines training with Guatemalan “Kaibil” special forces in Poptun, Guatemala in 2010 (Photo credit: public domain) ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-military-special-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=300%2C168&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-military-special-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=1000%2C560&ssl=1″ />In 1982, the Kaibiles massacred 226 people in the small Dos Erres village. According to the United Nations Truth Commission Clarification and reporting by ProPublica, the Kaibiles arrived in the middle of the night and accused the residents of being leftist guerrilla sympathizers.

The smallest children were reportedly killed by smashing their heads against trees and buildings, while older children were killed with a hammer. Adults were interrogated and tortured individually and the women were raped. The Kaibiles also reportedly cut fetuses out of pregnant women. After the interrogation, the adults were executed and the corpses were dumped in a well.

A few years after the massacre, one of the Kaibiles officers who had supervised the killing at Dos Erres, Pedro Pimental Rios, became an instructor at the School of the Americas. In 2012, he was extradited from the U.S. and sentenced to more than 6,000 years in prison for his participation in the atrocity.

Members of Guatemala’s elite “Kaibiles” special forces who committed the 1982 massacre at Dos Erres ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Guatemala-Kaibiles-special-forces-massacre.jpg?fit=300%2C189&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Guatemala-Kaibiles-special-forces-massacre.jpg?fit=540%2C340&ssl=1″ />

Members of Guatemala’s elite “Kaibiles” special forces who committed the 1982 massacre at Dos Erres ” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Guatemala-Kaibiles-special-forces-massacre.jpg?fit=300%2C189&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Guatemala-Kaibiles-special-forces-massacre.jpg?fit=540%2C340&ssl=1″ />In 1983, journalist Raymond Bonner reported on a classified summary of an April 1982 meeting between foreign policy advisers in the Reagan administration. The advisers proposed a series of secret and overt programs to contain the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and prevent revolutionary movements from spilling over into El Salvador and Guatemala.

One of the proposals included a $2.5 million budget for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for arms interdiction in Guatemala.

According to journalist Leslie Gelb, the arms interdiction program was managed by Argentina rather than by the U.S. directly. The Argentines and even U.S. intelligence service personnel allegedly worked directly with the paramilitary death squads during the Guatemalan genocide.

In one anecdote, former Delta Force member Stan Goff describes a conversation with a fellow special forces veteran working for the CIA’s paramilitary division in Guatemala in 1983:

The CIA man began spontaneously relating how he had participated in the execution of a successful ambush “up north,” two weeks earlier.

“North” was in the Indian areas: Quiche and Peten, where government troops were waging a scorched-earth campaign against Mayans considered sympathetic to leftist guerrillas.

He was elated. “Best fuckin’ thing I got to do since Nam.”

According to a declassified 1994 Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) memo, intelligence sources reported clandestine graves outside of a Guatemalan military facility and described Guatemalan soldiers “disappearing” captives by flying them over the ocean in a helicopter before pushing them to their deaths, a technique which was also used in Argentina.

After the Cold War, the Kaibiles were repurposed to fight the new greatest threats to U.S. national security: drugs, and later terror.

From 2007 to 2014, U.S. Special Forces training tripled in Latin America, mostly in the U.S. Department of Defense’s Southern Command’s (SOUTHCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) in the Caribbean, Central and South America.

The U.S. military continues to train the Kaibiles to this day.

A U.S. special forces soldier from the 7th SF Group trains a group of Guatemalan Special Forces “Kaibiles” in Poptun, Guatemala in 2015 ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-special-operations-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=300%2C162&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-special-operations-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=1000%2C540&ssl=1″ />

A U.S. special forces soldier from the 7th SF Group trains a group of Guatemalan Special Forces “Kaibiles” in Poptun, Guatemala in 2015 ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-special-operations-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=300%2C162&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-special-operations-forces-training-Guatemala-Kaibiles.jpg?fit=1000%2C540&ssl=1″ />The U.S. military’s “war on terror” in Latin America

While the Mexican military was fighting a war nominally against drug-trafficking organizations like the Zetas, the U.S. military was developing and spreading a new doctrine for waging a regional war on terror throughout Latin America.

A 2007 academic paper outlined a new distributed operational model for command and control (C2) for Special Operations Command in the U.S. SOUTHCOM AOR (SOCSOUTH), based on the approach of the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC).

The authors recognized the USMC approach as “better suited for counterinsurgency and non-combat environments, where the objectives are more ambivalent.”

The authors wrote:

In standard military maneuver operations where missions such as “attack that position,” are clearly defined, the [conventional] definition of C2 is sufficient. However, in an ambiguous environment where SOF often operates, the mission (e.g., plan and execute [Unconventional Warfare]) is not as clearly defined. As a result, a special operator in the field must be able to operate with maximum authority, flexibility, and agility to respond to immediate changes emerging from dynamic situations. The USMC definition reflects precisely how SOCSOUTH’s staff currently approaches C2 in its theater of operations.

Officers from the Colombian military that had been studying at the United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College at the Marine Corps University quickly recognized the advantages of the U.S. approach. According to a 2008 academic paper from a Colombian major:

The enemy’s ability to disperse in small units employing guerrilla tactics against conventional forces compels the regular armies to seek changes in doctrine. One of the alternatives to counter this opponents’ advantage is to incorporate the use of distributed operations.

Distributed Operations describes an operating approach that will create an advantage over an adversary through the deliberate use of separation and coordinated, interdependent, tactical actions enabled by increased access to functional support, as well by enhanced combat capabilities at the small-unit level.

[…]

Special Operations Forces are small units that work alone or in combination with one another in both direct and indirect military operations, often using tactics of unconventional warfare. The use of unconventional tactics is essential in modern warfare. The enemy employs different types of unconventional tactics and the only way to gain advantage against him is to do the same.

In another academic paper from the United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College in March 2010, a USMC officer elaborates his thesis as follows:

The best support the Department of Defense (DoD) can provide to help the Mexican government strengthen their security institutions are the skills of the U.S. Special Operations Forces.

[…]

U.S. military experience in El Salvador, Colombia, the Philippines, Iraq and Afghanistan would be of great value to the Mexican military. The “Colombia plan” […] was executed by the U.S. Southern Command and is an excellent template for counterdrug/security building in Mexico. In Colombia, SOF personnel were used to “teach intelligence collection, scouting, patrolling, infantry tactics, and counterterrorism.” The SOF role in Colombia was that of advisors and the U.S. units were, “forbidden to participate in counterinsurgency operations.” While utilizing SOF units in Mexico, the same restriction would more than likely be in place. Another outstanding example of the use of SOF in an advisory role took place in El Salvador in 1981. The U.S. congress approved the use of 55 soldiers to train and advise the El Salvadorian army. In 5 years, that army grew from 20,000 to 56,000 troops. A training facility created in El Salvador ensured the police became a better force and cut down on human rights violations.

According to an email from the private intelligence firm Stratfor published by WikiLeaks, an operational detachment from the 7th SFG began training Kaibiles and other special forces units from the Guatemalan police and military on March 20, 2009, in Petén.

The Stratfor email stated, “It has also been reported that the Green Berets [7th SFG] have also taken part in actual operations, possibly illegally as it is not in their official rules of engagement.”

The 7th Group advisory mission in Guatemala was also acknowledged in a publication from U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM), which noted that the Guatemalan SOF units were operational at the time which led to occasional interruptions of the training from deployments on actual missions.

On March 27, 2009, Guatemalan security forces claimed a Zetas training camp was discovered at a ranch in Quiché, but everyone fled when the security forces arrived, and they got away.

A month later, after a deadly shootout in Guatemala City, security forces seized thousands of small arms, grenades, and ammunition purportedly from the Zetas. The weapons and ammunition were eventually traced back to the Guatemalan military.

Three months into the 7th Group deployment in Guatemala, the “Matazetas” (“Zeta-killers”) made their debut on June 19, 2009, in nearby Cancún, Quintana Roo, with a grisly display of five executed bodies wrapped in duct tape along with a note which read, “We are the new group ‘Matazetas’ and we are against kidnapping and extortion, and we are going to fight against them in all the states for a cleaner Mexico.”

True to their word, the “Matazetas” began making appearances all over Mexico between 2009 and 2011, in Guanajuato, Veracruz, Michoacán, and Guerrero, among other places.

“Los Matazetas” in a video in 2011 ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/matazetas-mexico.jpg?fit=300%2C169&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/matazetas-mexico.jpg?fit=1024%2C577&ssl=1″ />

“Los Matazetas” in a video in 2011 ” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/matazetas-mexico.jpg?fit=300%2C169&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/thegrayzone.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/matazetas-mexico.jpg?fit=1024%2C577&ssl=1″ />In another internal email from Stratfor on the possible involvement of the U.S. Marine Force Recon (MFR) in Mexico, a confidential human source referred to only as MX1 in the email stated that the U.S. Marines were secretly operational in Mexico.

According to reporting from Bill Conroy, MX1 was likely Fernando de la Mora Salcedo, a diplomat who worked at the Mexican consulates in El Paso and later Phoenix. The exact date of the email is unknown but would have been some time between 2008 and 2011 according to the same reporting.

In the Stratfor email, MX1 stated:

Information about U.S. military involvement in Mexico is provided only as a need to know basis. The Americans have been adamant about this, and we agree even more. Therefore, I can confirm that there is Marine presence, but I don’t know if it is MFR.

In June 2010, U.S. Marines and Navy personnel traveled to Manzanillo, Colima, for the Partnership of the Americas and Southern Exchange program, to train with the Mexican Navy in room-clearing and hand-to-hand combat. The Marines were from Charlie Company, 3rd Amphibious Assault Battalion, 1st Marine Division. The Navy forces were not specified.

In July 2010, one month after the Partnership of the Americas and Southern Exchange training in Manzanillo, the Mexican Navy killed Sinaloa cartel boss Ignacio “Nacho” Coronel, the “King of Crystal,” in a raid in Zapopan, Jalisco. Nacho Coronel was allegedly a multi-ton cocaine trafficker who shipped loads from Colombia through the Pacific.

His niece, Emma Coronel, was married to Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. The death of Coronel reportedly caused the Guadalajara-based Milenio cartel to split into two factions, one of which, “Los Torcidos” (The Twisteds), was supposedly led by Nemesio Oceguera Cervantes, better known as “El Mencho.”

In September 2010, 40 U.S. Marines from Alpha Company, 2nd Assault Amphibian Battalion from Camp Lejeune, N.C. traveled to Poptun, Guatemala to train with the Kaibiles as a part of the Subject Matter Expert Exchange (SMEE) program.

An unusual sequence of events followed an incident in which 49 bodies were left in the streets of Boca del Rio, Veracruz, on September 23, 2011. A group of five masked men purporting to be the “Matazetas” appeared in a video the following day, claimed responsibility for the killings, and apologized to the public.

Three days later, the real “Matazetas” appeared in a video, this time heavily armed in the fashion that “CJNG” would later be known for in their propaganda.

According to reporting from Mexico’s Animal Político:

In that statement, the hitmen of the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel assure that “since 2006 we have been fighting for the tranquility and safety of each and every one of our fellow Veracruz countrymen,” whom they asked to report any Zeta they are aware of, but not before the police, but only before the Army and the Navy, the only corporations that “to date have not been corrupted with their money offers in this state,” while, they clarified, “for what corresponds to us, we will in our own way: we have given a preview by killing each one of the Zetas that we grab.”

The incident led to widespread speculation in the media that Mexico could be experiencing the phenomenon of paramilitarism similar to Colombia and Guatemala.

On October 16, 2011, anonymous military sources in Colombia reportedly confided to El Tiempo (English synopsis from Insight Crime) that four former Colombian special forces soldiers were training, advising, and assisting the Zetas.

The story also mentioned that the services of the former Colombian military were in demand as soldiers of fortune all over the world, as confirmed by a 2011 story in the New York Times which described a “secret army” of Colombian mercenaries created in the United Arab Emirates by Erik Prince, the former Navy SEAL and founder of the private military contracting firm Blackwater.

Over time, “Los Torcidos” in Jalisco, Colima, and Michoacán, and “Los Matazetas,” in Veracruz and Quintana Roo, were recognized as a single entity: the Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación.

U.S. training, Colombian counter-insurgency, and Mexican cartels

In August 2012, Wired reported that 200 U.S. Marines were sent to Guatemala to patrol along the Pacific coast in the ongoing Operation Martillo, which began on January 15, 2012, in addition to a combat mission to clear the Zetas.

The U.S.-led operation included military personnel and law enforcement agents from Belize, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, France, Guatemala, Honduras, the Netherlands, Nicaragua, Panama, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

Wired wrote:

The war on drugs just got a whole lot more warlike. Two hundred U.S. Marines have entered Guatemala, on a mission to chase local operatives of the murderous Zeta drug cartel.

The Marines are now encamped after having deployed to Guatemala earlier this month, and have just “kicked off” their share of Operation Martillo, or Hammer. That operation began earlier in January, and is much larger than just the Marine contingent and involves the Navy, Coast Guard, and federal agents working with the Guatemalans to block drug shipment routes.

It’s a big shift for U.S. forces in the region. For years, the Pentagon has sent troops to Guatemala, but these missions have been pretty limited to exercising “soft power” – training local soldiers, building roads and schools. Operation Martillo is something quite different.

According to an article from Marine Times first published on July 7, 2014:

U.S. Marines have worked closely with their Colombian counterparts for generations — particularly over the past decade — and the Colombians are now sharing that expertise with friendly nations across the Americas.

“Right now, we are already developing training activities with allies like Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and the Dominican Republic,” Maj. Gen. Hector Pachon Cañon, the Colombian marines’ commanding general, told Marine Corps Times. “In those countries right now are Colombian Marines, spreading training we received from the United States Marines.”

The influence of the U.S. Marines is apparent in everything the Colombians do, from their boot camp and uniforms to the importance they place on ethos and noncommissioned officers’ leadership traits.

[…]

“Senior U.S. officials in State and Defense will tell you that the mil-to-mil relationship between the United States and Colombia is the best they have ever seen anywhere in the world.”

General John F. Kelly, USMC, the commander of U.S. SOUTHCOM from 2012 to 2016, apparently shared that sentiment. At a congressional hearing on April 29, 2014, General Kelly conveyed his gratitude to Colombia for serving as proxies for training personnel the U.S. is prohibited from working with because of human rights violations.

According to General Kelly:

We’re not focusing in the same way on countries that are, today, very close to going over the edge, where Colombia was in the 90s. They’re just a few inches away from falling off the cliff. Yet we’re restricted from working with them, for past—‘sins,’ in the 80s.

The beauty of having a Colombia—they’re such good partners, particularly in the military realm, they’re such good partners with us. When we ask them to go somewhere else and train the Mexicans, the Hondurans, the Guatemalans, the Panamanians, they will do it almost without asking. And they’ll do it on their own. They’re so appreciative of what we did for them. And what we did for them was, really, to encourage them for 20 years and they’ve done such a magnificent job.

But that’s why it’s important for them to go, because I’m–at least on the military side–restricted from working with some of these countries because of limitations that are, that are really based on past sins. And I’ll let it go at that.

In May 2015, an operation supposedly to capture “El Mencho” failed catastrophically, when a helicopter was shot down purportedly by the elite “praetorian guard” protecting the cartel’s leader, near Villa Purificación, Jalisco.

In a prelude to the spectacle in Culiacán four years later, forces supposedly loyal to “El Mencho” mobilized simultaneously in four states, burning vehicles and erecting blockades with burned out tires.

According to a column about the incident in the Mexican national security website Estado Mayor:

The criminal group in charge of the security of Nemesio Oceguera Cervantes, leader of the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel, is a mixture of mercenaries of different origins. They are “stateless,” as General Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, Secretary of National Defense, called them. They are responsible for the death of eight elite soldiers and a Federal Police agent, who died after the downing with an RPG-7 grenade launcher of a troop transport helicopter. This group demonstrated a level of training rarely seen in the country, unprecedented on a geographical scale that covered four states. How was it possible that more than a hundred simultaneous offensive actions were not planned in advance? Why did the military intelligence fail and the narco set up a deadly ambush only possible with inside information?

In the early hours of Friday, May 1, Major General Miguel Gustavo González Cruz could not believe the reports he received in real time. The commander of the fifth military region, which encompasses the military zones of five western states of the country, was in constant communication with his colleague, fellow divisional Roble Arturo Granados Gallardo, chief of the National Defense Staff. A command that acted as the first “ring” of protection for Nemesio Oceguera Cervantes, leader of the criminal organization calling itself the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel (CJNG), had made contact with the aircraft that was at the forefront of the operation launched that morning to capture him.

The outfit in charge of capturing “El Mencho” was not just any army unit. It was a section, around 40 troops, of members of the GAFE (Special Forces Aircraft Group) of the High Command, belonging to the Special Forces Corps of the Mexican Army and Air Force, a unit commanded by Brigadier General Miguel Ángel Aguirre Lara.

The elite soldiers had been attacked from the ground by RPG-7 rocket launchers and had been targeted by assault rifles from different points. The support aircraft managed to target several of the attackers, but as the minutes passed, the criminal leader’s “ring” of protection had managed to cover his flight after shooting down the helicopter that was in the vanguard and that was carrying the troops that would specify the detention. This blow would ruin the operation.

That was one of the reasons that made Generals González Cruz, Granados Gallardo and Brigadier Aguirre Lara extremely concerned. The troops had made contact with a special corps that guarded Oceguera Cervantes, the group had been identified for some time, it was known that it consisted of deserters from the Mexican army, who acted supported by former Guatemalan soldiers and some former U.S. Marines who offered their services to the drug cartels via their contacts in Central America.

Members of this group were those who allegedly trained the so-called “matazetas,” the paramilitary body that appeared in Veracruz three years ago and who are known to operate in areas of the Gulf, the State of Mexico and Michoacán where their enemies are present.

Military sources consulted in Jalisco and Mexico City agreed that the idea of maneuver, reaction capacity, planning techniques and the use of more sophisticated weapons was something that some of the members of the group were known to be prepared for that guarded “Mencho.”

Those protecting him would be “latest generation” mercenaries, “soldiers of fortune,” some with experience in Afghanistan and Iraq, retired and others discharged, who offer their services as praetorian guard of the leader of the CJNG, said a military source in the capital of the country.

This group was identified in recent days by journalists Raymundo Riva Palacio and Salvador García Soto, who separately recorded in their columns the possible participation of former U.S. Marines in the reaction operation that shot down the helicopter and cost the lives of eight members of the GAFE of the High Command as well as a federal policeman.

What the federal forces did not discuss was that the group that guarded “El Mencho” also received intelligence information in real time, which allowed them to act in advance, prepare the counterattack and shield the escape from the Villa Purificación area, the Jalisco municipality where the helicopter was shot down, leaving seven dead at the scene, and several wounded, one of whom later died in Mexico City.

Many immediately suspected the operation had failed due to leaks from the Federal Police, long suspected of ties to drug trafficking, who had been invited to participate in the operation despite doubts about their integrity.

However, according to the Estado Mayor column, an anonymous military official blamed Jalisco Governor Aristóteles Sandoval and Attorney General Luis Carlos Nájera for leaking information to the “CJNG.”

From April 3 to 5, 2018, Colombian Vice President Óscar Naranjo made a trip to Mexico without much fanfare. The visit was reportedly to discuss operations of the Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación cartels in Colombian territory with Mexico’s Attorney General’s office.

On May 22, 2018, Jalisco Labor Secretary Luis Carlos Nájera, the former attorney general during Governor Aristóteles Sandoval’s administration, blamed for the failed operation to capture El Mencho, was attacked by gunmen and injured in a failed attempt on his life. A child was killed and 16 people were injured.

The attack had many similarities with the failed attack on Omar García Harfuch on June 26, 2020, and “CJNG” was alleged to be responsible for both incidents.

The attack on Luis Carlos Nájera was the first action attributed to “Grupo Élite,” a mysterious CJNG special forces unit comprised by the same inner circle protecting “El Mencho.”

At a press conference after the attack on Nájera, Aristóteles Sandoval revealed that “CJNG” recruited Colombians with military and guerrilla warfare training and experience. Sandoval described how state authorities had been aware of the presence of Colombian mercenaries or soldiers in Jalisco since 2013 or so, and that this information had been passed along to the federal Attorney General’s Office (PGR).

According to Governor Sandoval:

We told the PGR about this four years ago [approximately 2014], we know what the training is like, what the operation is like and that is why it is important to find these camps that are generally installed in remote places like the mountains.

[…]

We have reports for five years, we have indicated the spread of this cartel with strategy and above all with the inclusion of experts, not only from Colombia, but from other parts of the world.

On June 1 and 2, 2020, Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF), in coordination with the U.S. Treasury Department froze more than $1 billion USD in “CJNG” assets in Operation Blue Agave.

Two days later, a photograph appeared on social media showing a CJNG Grupo Élite logo with the Guatemalan Kaibiles’s famous slogan: Si avanzo, sígueme. Si me detengo, aprémiame. Si retrocedo, mátame!

On July 17, 2020, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced that control of the port in Manzanillo would be handed over to the Mexican military.

Later that evening, “CJNG Grupo Élite” released one of the most spectacular propaganda videos ever produced by a paramilitary group in Mexico. The video showed an intimidating convoy of 22 armored and painted vehicles and 74 men dressed impeccably in matching uniforms.

The video may have been filmed near Tomatlán, Jalisco. It was rumored that a wave of killings in Tomatlán in early 2020 was related to a dispute in Puerto Vallarta involving several Colombian “CJNG” associates.

On July 18, 2020, 20 students from the neighboring state of Guanajuato were kidnapped in Puerto Vallarta, a sister city of Tomatlán. The case had eerie similarities to the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students in Iguala, Guerrero, in 2013.

On December 18 2020, Aristóteles Sandoval, the former governor of Jalisco, was assassinated by a female gunman in a professional hit in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco.

According to the current Jalisco attorney general, the staff at the restaurant supposedly cleaned all traces of physical evidence at the crime scene and erased security footage of the attack. The killing was attributed to “CJNG.”

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 6th, 2021

May 6th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: