Hera, also known by her Latin title as Juno, is best known in Western culture as the wife of Zeus, king of the gods. While technically subordinate to him, Hera is never a submissive figure, in fact in the opening of Virgil’s Aeneid, he calls her Iunonis iram meaning wrathful Juno. In the stories and legends surrounding her, she exerts considerable power and influence often – as is the case with many mortal marriages – in defiance of her husband’s wishes. As anyone knowledgeable about Greek mythology can attest to, she exhibits a powerful presence permeating both the heavenly and earthly realms.

One feature about Hera that is less known amongst students of Greco-Roman lore is the extensive history of interpretation about her. It is a history that begins prior to and extends beyond the Hellenistic era. Indeed, Hera may have had origins not in the Mediterranean but in Mesopotamia, and when Roman Christianity succeeded in eliminating most of the ancient pagan pantheon, she survived and continued to thrive albeit in an altered form. This article will provide a brief overview of this interpretive history looking at her ancient Near Eastern counterparts as well as her continued, post-classical, presence.

Hera, goddess of marriage, had a volatile relationship with Zeus, king of the Greek pantheon. ( Public domain )

The Hera of Greco-Roman Mythology

Like Tiberius in Roman history, Hera was an unwilling participant in her ascension to royal power. As the youngest of the Olympians, she was saved by her brother Zeus when he rescued his siblings from their father Kronos (Latin: Saturnus). Later, Zeus tricked her into marrying him some say by taking the form of a cuckoo, and in that way she became queen of the gods. Though Hera was eventually venerated as the patron goddess of marriage, her own relationship with Zeus was volatile due to the latter’s frequent infidelities. Ironically, while the king of the gods was notorious for his sexual exploits, Hera was frequently described by ancient Greek and Roman authors as a married “virgin” though in accounts by both Homer and Virgil she has frequent sex with her husband.

While Zeus continued to engage in affairs with other, usually mortal, women, his adultery was often balanced out by Hera’s cunning and spiteful tendencies behind the scenes. Unable to punish the most powerful being in the cosmos, Hera often took out her frustrations against Zeus on the only group of people she was able to harm: Zeus’ human lovers and their demi-god children. A notable example of this is seen in the birth story of Dionysus where Hera tricks Zeus into accidentally incinerating Semele, Dionysus’ mother, facilitating the need for Zeus to incubate the fetus of the god until it matured to birth.

The most notable instance of Hera’s wrath towards Zeus’ human lovers is seen in the myth of Hercules, though here Hera’s attention is directed more towards the demi-god himself. Hera taunts Hercules throughout his life and is directly responsible for the demi-god’s fit of madness that leads to Hercules’ murdering his own children and going into exile afterwards. It is this horrendous act, brought on by the influence of Hera, that also leads Hercules to seek redemption by means of completing twelve great labors for king Eurystheus.

Yet Hera is not entirely capricious in Greco-Roman tradition and was far more loved than feared by her human subjects. Even in the Hercules story, the demi-god himself brings offerings and sacrifices to Hera. Her love for particular nations and persons is evident most notably in Virgil’s Aeneid where she is the patron goddess for the North African Carthaginians who, as Virgil notes, possess her very chariot in their city. At the same time, her love for Carthage comes at the expense of the Trojans whom Hera persecutes and pursues throughout the Aeneid in a vain attempt to prevent the fulfillment of a divine prophecy. This prophecy states that Troy’s descendants (i.e. the Romans) will one day overthrow and destroy Carthage.

According to Greek mythology, Hera’s wrath knew no bounds when it came to her husband’s infidelities. She is known for her persecution of Heracles (Hercules), Zeus’ favorite illegitimate son, known as the Labors of Hercules. ( Public domain )

The Hera of Ancient Near Eastern Tradition

Though most popularly associated with the Greco-Roman pantheon, it is possible that Hera’s origins were pre-Hellenic. The goddess seems to have been inspired, and indeed has many parallels to, older deities such as Astarte (Mesopotamian: Ishtar). Like Zeus with Hera, Astarte’s loyalty to her consort El is contrasted with the Near Eastern god’s cohabitations with both earthly and divine women (e.g. Anath). Furthermore, Hera appears to have inherited several of the titles of her Near Eastern counterparts most notably that of the “queen of heaven” (Greek: stratia tou ouranou , Latin: regina caeli ) as she is called by Homer.

In certain Near Eastern religious traditions, the veneration of the queen of heaven was far more popular than that of the (usually male) deity officially sanctioned and approved of by the clergy. One sees this most notably in ancient Israelite religion where the queen of heaven, in this case Asherah (the Hebrew equivalent of Astarte) is worshipped to the disapproval and condemnation of the biblical prophet Jeremiah. Towards the beginning of his oracles, the 7 th century seer makes the following observation about his Judean peers:

Ha-nasim lasot baseq la’asot kavvanim limleket ha-samayim

The women kneed the dough to make cakes to the queen of heaven

(Jeremiah 7:18)

As in Greek mythology, while the highest god in the pantheon (in this case, Yahweh) was male the most popular deity among the common people was the high god’s female consort. In unorthodox Israelite religion, in contrast to the type of religion presented in the Old Testament, the Hebrew God was married with a wife. Not only the gender but the specific attributes of the gods may account for this. Both El and Yahweh (whom the biblical authors later merge and identify as one and the same) were seen as transcendent deities. Like Zeus, they dwelt high in the heavens and had little interaction with humankind. Hera, and her Near Eastern precursors, were likely seen as more motherly, nurturing deities who took an active concern in the affairs of mortals and especially women in their domestic and reproductive needs.

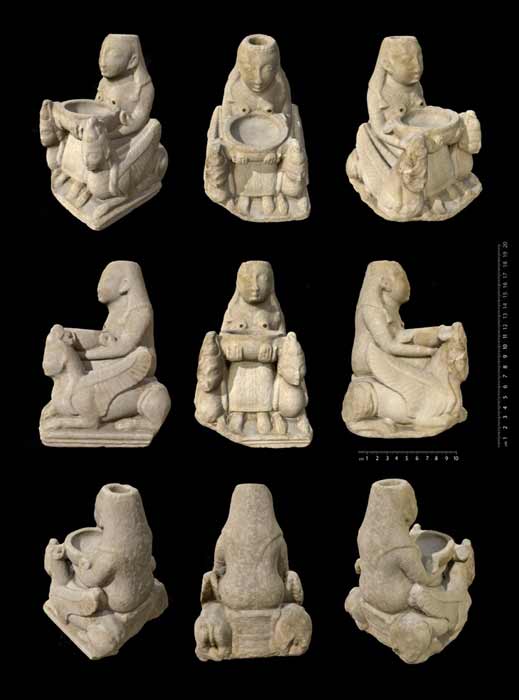

The goddess Hera appears to have been inspired by older deities such as the Near Eastern goddess Astarte. (Amfeli / CC BY 4.0 )

Hera in the Latter Roman Empire

If Hera precedes many of her Greco-Roman counterparts in having Near Eastern precursors, she would also outlive many of them as Rome started to reject and abandon their old gods. In the late 4 th century, when Christianity had come to dominate Roman society and culture, the last pagan emperor, Julian, who is kindly referred to by his Christian opponents as “the apostate,” turned to Hera in a last ditch effort to revive the Greco-Roman faith. Recognizing that the Christians drew many converts and followers to their religion through the use of hymns, Julian attempted to emulate this feature in his own religious renaissance composing a hymn to the mother of the gods.

Though identified as Attis, a Cybele goddess, Julian uses terminology and associations such as “mother of the gods” and “the one who provides fertility” which Roman listeners would have identified as attributes of Hera. For example, later in the hymn, Julian notes that this “mother” has existed with Zeus for all time suggesting an implicit allusion to Hera and highlighting Hera’s attribute as creating life through birth.

Who then is the mother of the gods? She is indeed the fountain of the intellectual and demiurgic gods who govern the apparent series of things: or certainly a deity producing things, and at the same time subsisting with the mighty Jupiter; a goddess mighty, after one mighty, and conjoined with the mighty demiurgus of the world. She is the mistress of all life, and the cause of all generation, who most easily confers perfection on her productions, and generates and fabricates things without passion, in conjunction with the father of the universe.

Though Julian’s reform efforts ultimately failed, much of the terminology and language associated with Hera was in fact retained in Roman and later medieval Christian liturgy not in reference, obviously, to Hera herself but adapted to suit a monotheistic context. The queen of heaven, in Roman Catholic tradition, was no longer Hera of the Greco-Roman pantheon but the mother of Jesus Christ, the blessed Virgin Mary . The title, queen of heaven, appears in numerous Marian antiphons such as Ave Regina Caeloum:

Ave, Regina caelorum, / Greetings, Queen of Heaven

Ave, Domina Angelorum / Greetings, Lady of the Angels

Salve, radix, salve, porta / Welcome, O root. Welcome, O gate

Ex qua mundo lux est orta / From which the light has arisen into the world.

As many classicists are fond of saying, the Greek gods never really died out. Rather they morphed into different things. For Christian Rome, they eventually became the various demons mentioned in the Bible. For the thinkers responsible for the European Renaissance, they became personifications of the best of human attributes and abilities. That no god can ever really die is certainly true of Hera who continues to fascinate and indeed exist in the Western mind. We find her in modern novels such as Madeline Miller’s Circe and in movies and shows such as Clash of the Titans and Troy: Fall of a City . As long as us mortals continue to be plagued with our worldly problems and concerns, whether these be our romantic relationships or ability to procreate, so will Queen Hera, in one form or another, continue to grace us with her presence as well.

Top image: The origins of the goddess Hera extend beyond the Mediterranean and the Greek pantheon. Source: Public domain

By Adam Oliver Stokes

References

Christ, H. I. 2002. Myths and Folklore . Amsco College Publications.

Evslin, B. 2012. Hercules. New York: Open Road.

Frankfort, H. 1978. Kingship and Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature . Phoenix: Oriental University.

Kennelly, B. and Rotondi, R. 2017. Queen of Heaven: Mary’s Battle for Souls . Charlotte, NC: Saint Benedict Press.

Miller, M. 2020. Circe. New York: Back Bay Books.

Murdoch, A. 2008. The Last Pagan: Julian the Apostate and the Death of the Ancient World . Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions.

Namm, D. 2011. Greek Myths . New York: Sterling Children’s Books.

Pritchard, J. 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts relating to the Old Testament . Princeton: Princeton UP.

Ranck, S. A. 2006. Cakes for the Queen of Heaven: An Exploration of Women’s Power, Past, Present and Future . iUniverse.

Tripp, E. 2007. The Meridian Handbook of Classical Mythology: An Alphabetical Guide . New York: Plume.

Vidal, G. Julian. New York: Vintage, 2003

Wright, W. C. [Trans]. 1923. Julian, Volume III-Loeb Classical Library, no. 157 . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 10th, 2021

April 10th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: