CT scans of an Egyptian mummy from approximately 1,200 BC have exposed a type of mortuary treatment which has not been documented in the Egyptian archaeological record before now. The individual is the first known case of an ancient Egyptian ‘mud mummy’ and its existence has led archaeologists to reconsider their beliefs about how nonroyal ancient Egyptians preserved their deceased loved ones.

Karin Sowada from Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia led the analysis of the unnamed mummified adult and is the lead author in the new study published in the journal PLOS ONE . The researchers write in their paper that their scan shows the individual was “fully sheathed in a mud shell or carapace.”

Mummified individual and coffin in the Nicholson Collection of the Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney. A. Mummified individual, encased in a modern sleeve for conservation. B. Coffin lid. (Sowada et al, PLOS ONE/ CC BY 4.0 )

Live Science reports that an English-Australian politician named Sir Charles Nicholson bought the mummy along with a lidded coffin and mummy board (a wooden cover that was placed over the body) when he traveled to Egypt in 1856-1857. It has been in the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney since 1860, however the study authors explain the mummy’s unique mud shell wasn’t noted prior to the computed tomography (CT) scan because the “carapace was placed between layers of linen wrappings thus it was not externally visible.”

Scanning the Mud Mummy

In 1999, Sowada and other researchers completed a full CT scan of the mummified body, however the team decided to rescan the body with more up-to-date technology. Their scans in 2017 have revealed some surprising finds, which are just now being reported.

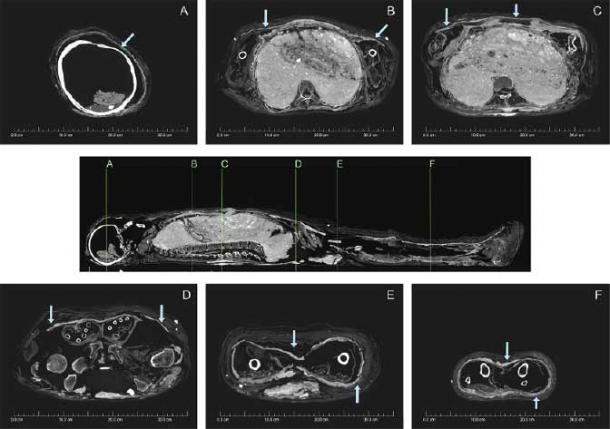

CT images show the mummified person from different angles. The carapace can be seen as a thin white line (arrows). (Sowada et al. Courtesy Chau Chak Wing Museum and Macquarie Medical Imaging / PLOS ONE/ CC BY 4.0 )

First, the scans exposed the mud carapace which surrounds the whole body. When fragments of the mud shell were removed from the head area, the researchers discovered that it has three layers – a thin layer of mud as the base that was coated with a white calcite-based pigment, and finally a red-painted surface layer.

Another Twist – Something’s Amiss with the Mummy and its Coffin

The authors also used the CT images to get a good look at the skeleton, paying particular attention to the hip bones, jaw, and cranium, and they used this information to identify the body as an adult female. She probably died when she was between 26-35 years old and radiocarbon dating of textile samples from the linen she was wrapped in suggest that she died sometime during ancient Egypt’s late New Kingdom period (c. 1200-1113 BC). They write in their paper that this challenges previous DNA results which had identified the body as male.

A release posted on EurekAlert! reports that the coffin has an inscription identifying its owner as a woman named Meruah. The iconography suggests it was made sometime around 1000 BC. This means that the mummified body and the coffin were not a matching pair – the body is approximately 200 years older than the coffin. The researchers note in their paper that “Local dealers likely placed an unrelated mummified body in the coffin to sell a more complete ‘set,’ a well-known practice in the local antiquities trade.”

Street vendor selling mummies in Egypt, circa 1865. ( Public Domain )

Mimicking Elite Ancient Egyptian Mortuary Practices

The study authors write in the paper that their scans also revealed that the mummy suffered “post-mortem damage in unknown circumstances” – although they suggest it may have had to do with grave robbers. The researchers believe that “the individual was then subject to some rewrapping, packing and padding with textiles, and application of the mud carapace” to try to reunify and restore the body.

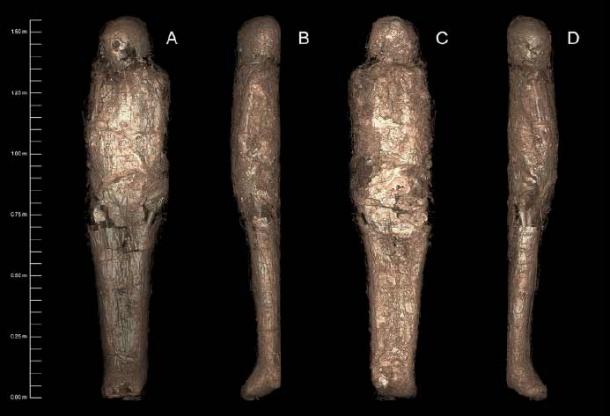

3D-rendered CT images of the mummified person, showing the mud carapace which surrounded the body – demonstrating a previously unknown mortuary practice. ( Sowada et al. Courtesy Chau Chak Wing Museum and Macquarie Medical Imaging / PLOS ONE/ CC BY 4.0 )

This was important because in ancient Egyptian mortuary practices and beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife, the deceased were associated with the god Osiris. The rewrapping, packing and padding of the damaged body “would have served to reunify the corporeal integrity of the deceased and ensure their continued association with Osiris,” according to the researchers. The authors also think that mud could have also been an appropriate choice for the carapace because of the “associations found in the textual and archaeological record between the Osiris’ re-birth and the renewed fecundity of Egypt’s agricultural soil following the Nile inundation.”

Using a mud shell likely served a practical, restorative purpose, but the researchers also believe that having a mud carapace may have also allowed the deceased’s loved ones to emulate mortuary practices that were used by more elite members of society. The study paper mentions several resin carapaces on the bodies of elite individuals who lived in the 19th and 20th dynasties, such as Rameses II, Amenhotep III , Merenptah, Seti II, and Rameses III. More evidence supporting this idea is the red paint on the head of the mud carapace, since the researchers write that Pharaoh Rameses V (c. 1147–1143 BC) likewise had a face “painted an earthy red colour, like that of the mummies of many priests.”

Finally, the researchers mention that there are some ambiguous examples of shells being used in the mortuary process for “mummified bodies of lesser status” but “The mud shell encasing the body of a mummified woman within the textile wrappings is a new addition to our understanding of ancient Egyptian mummification .” No one knows for certain yet how popular this process may have been in the funerary practices of everyday people during the late New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

Top Image: This ‘mud mummy’ has revealed a previously unknown mortuary practice for non-elite ancient Egyptians. Source: Sowada et al, PLOS ONE/ CC BY 4.0

By Alicia McDermott

Ancient Origins Tours will be investigating the Qasr el-Sagha temple, the Egyptian Labyrinth, and Amenemhat III’s pyramid at Hawara as part of a very special expedition in Egypt in September 2021. Why not join us for this unique experience that will bring you closer than ever before to Egypt’s first female ruler, whose story is now being told for the first time. The trip will include writer and author Andrew Collins, who will be speaking extensively about Sobekneferu and her world.

For more information on Ancient Origins Egypt Tour click here .

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 4th, 2021

February 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: