If there is a single event that made Sparta ’s military legend a seminal moment when the ‘Bronze Lie’ was forged, it is the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, fought 10 years after Marathon. Nearly everything committed to popular memory about this battle is wrong, including the notion that it was its own battle at all – when in fact it was a holding action meant to delay the Persian army, while the far more important naval fight at Artemisium (named for the nearby temple of Artemis), so inextricably linked to Thermopylae that the two actions should be considered a single battle, unfolded.

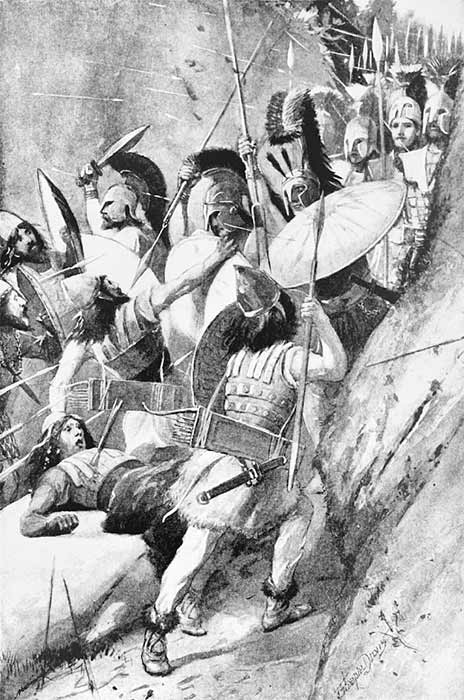

Scene of the Battle of the Thermopylae by John Steeple Davis ( Public Domain)

The Spartan King Leonidas’ famous reply: molon labe (come and take them), to the Persian king Xerxes’ demand that the Spartans lay down their arms, has become a rallying cry for far-right groups around the world, particularly among American ‘gun rights’ advocates such as the National Rifle Association (NRA). What these right-wing groups always conveniently leave unmentioned is that Xerxes did come and take them, and in very short order.

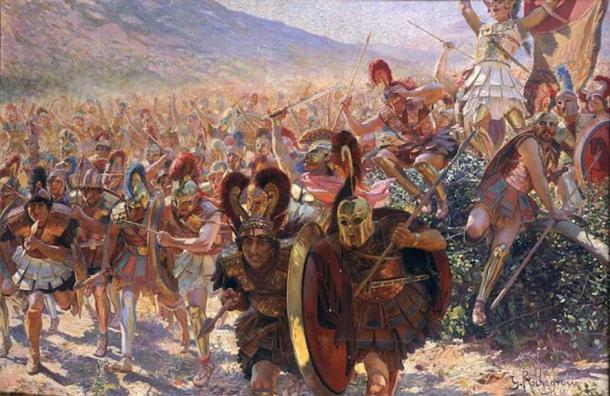

Greek troops rushing forward at the Battle of Marathon, Georges Rochegrosse (1859) ( Public Domain )

Xerxes Mobilization

Persia’s King Darius surely smarted from the humiliating and unexpected defeat at Marathon and began preparing a new expedition to avenge Persian honor and bring the Greeks to heel once and for all. He did not live to see it depart. His death in 486 BC put it to his successor, Xerxes I, to finish the job, a work further delayed by a revolt in Egypt and possibly Babylon, which tied up both the army and the great king ’s attention.

So, it was not until 481 BC that Xerxes finally mustered his army and fleet, wintering them in Lydia (on modern Turkey ’s west coast) due to storms destroying the bridges he had constructed across the Hellespont (the Dardanelles – the narrow strait that separates Europe from Turkey). A second bridge was constructed from ships lashed together, and a massive invasion preparation program was undertaken, including the laying in of supply depots along the army ’s projected path, the construction of roads, and the digging of a canal through the Athos peninsula, to allow ships to transit without exposing them to the storms that had scuttled the first invasion attempt in 492 BC.

Like this Preview and want to read on? You can! JOIN US THERE ( with easy, instant access ) and see what you’re missing!! All Premium articles are available in full, with immediate access.

For the price of a cup of coffee, you get this and all the other great benefits at Ancient Origins Premium. And – each time you support AO Premium, you support independent thought and writing.

Based on an extract from The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy by Myke Cole, Osprey Publishing.

Myke Cole has had a colorful and varied career, with service in war and crisis response with the CIA, the DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency), and the ONI (Office of Naval Intelligence). He is the author of The Bronze Lie: Shattering the Myth of Spartan Warrior Supremacy and Legion versus Phalanx: The Epic Struggle for Infantry Supremacy in the Ancient World

Top Image : Leonidas at Thermopylae, by Jacques-Louis David (1814). ( Public Domain )

By Myke Cole

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 19th, 2021

August 19th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: