Readers will probably know that Stonehenge’s design highlights the longest and shortest days of the year, but it is not always understood that its strange configuration was designed to enable every day and every month in the year to be counted and tracked by its resident timekeepers. The passage of time was very important to prehistoric people. Farmers needed to be able to identify propitious days for sowing, harvesting, trading and religious festivals. As the Old Testament said: “To everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under the heaven.” Located at the meeting point of ancient trackways, the Stonehenge calendar was as important to the time regulation of prehistoric England as Greenwich time is today.

When Stonehenge was constructed in its final form around 2,500 BC there were no clocks or watches as we know them, but the universe provided methods for calculating and monitoring the cycles of the year through the movements of sun, moon, stars, and planets. Few if any other stone circles were primarily designed as calendars, but Stonehenge surely was.

The famous standing sarsen stones at Stonehenge form a key part of the Stonehenge calendar, which marked the passage of the seasons in prehistoric times. ( Leonid Andronov / Adobe Stock)

The Thirty Large Sarsen Stones of the Stonehenge Calendar

It is not a coincidence that thirty large sarsen stones were erected in a circle at Stonehenge. These represented the thirty days in each lunar month and the thirty stone lintels which connected them represented the thirty nights of each lunar cycle. Stonehenge timekeepers presumably moved a marker (boulder, carving or seasonal offering) each day around the circle to count out the days of the lunar month. The moon’s cycle of 29.53 days also mirrored the female human fertility cycle. The stone Stonehenge calendar circle reflected the shape of the sun and the full moon and the recurrent nature of seasonal time.

Within the circle five trilithons, or freestanding doorways, were erected each consisting of two vertical boulders with a stone lintel joining them across their top ends. These trilithons were arranged in the shape of a horseshoe, open-ended towards the north-east avenue of Stonehenge. At midsummer dawn the largest central trilithon received the sun’s rays which shone down the approach avenue and passed between two “heelstones” (96 and 97).

In ancient times the Earth Mother was regarded as a female deity who progressed each year through the four stages of maiden, mother, queen, and old woman. The Earth Mother was deemed to be fertilized by the Sky Father who seemed to enter her every night.

This simple belief survived into modern times. In the nineteenth century Sitting Bull is credited with these words: “Behold, my friends, the Spring is come, the Earth has gladly received the embraces of the Sun, and we shall see the results of their love.”

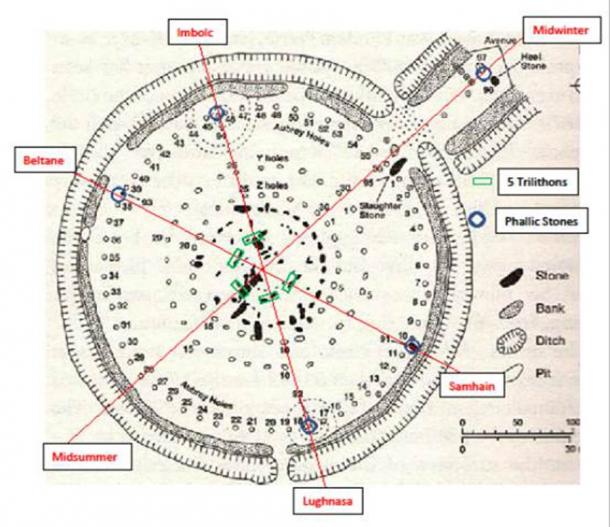

The four lesser trilithons of the Stonehenge calendar were probably identified with the four seasons in an anticlockwise direction: Imbolc being the northern trilithon, Beltane the north-western one, Lughnasa the southern trilithon and Samhain the south-eastern one. (Author provided)

The Sun God’s Phallus and the Earth Mother’s Vulva

It is generally agreed that at Stonehenge the Sun God’s phallus was represented by the Heel Stone(s). The Stonehenge trilithons represented the Earth Mother’s legs and vulva. A shaft of sunlight coming along the Avenue and penetrating between the uprights of the Great Central Trilithon therefore indicated fertilization of the whole Earth Mother at midsummer. The Sun God himself would be renewed six months later at the midwinter solstice as a result of this impregnation.

The four lesser trilithons represented the Earth Mother in her seasonal forms of maiden, mother, queen, and old woman (spring, summer, autumn and winter). Each of these was served by one of four other phallic stones (91, 92, 93, 94), which stood just inside the circular bank surrounding the stone Stonehenge calendar. Only one is still visible and it has fallen over. The other three are represented by a stump and two stone-holes which have been excavated. The diagonals of the rectangle formed by these four stones intersect at the center of the circle. The four smaller trilithons were set up to straddle these diagonal lines. The four corners of this rectangle may have served as sighting points when the trilithons were first erected, but they were probably also regarded as phallic servants of the goddess in each of her seasonal forms.

Sir Norman Lockyer established that at sunset during the first week in May the northwest phallic stone (93) would have cast a haloed shadow through the northwest trilithon, the center of the circle and the southeast trilithon. Conversely in early November the rising sun would have cast a shadow over the south eastern phallic stone (91) in the opposite direction. The dates of the Beltane and Samhain festivals were thus indicated. And the February and August dates for the other quarterly festivals of Imbolc and Lughnasa were fixed by alignment of pillars 92 and 94 through trilithons on the other diagonal of the rectangle. The four lesser trilithons were probably identified with the four seasons in an anticlockwise direction: Imbolc being the northern trilithon, Beltane the north-western one, Lughnasa the southern trilithon and Samhain the south-eastern one.

There are twelve full lunar months in every year and these twelve months are represented in the Stonehenge calendar by the twelve standing sarsen stones. (garethwiscombe / CC BY 2.0 )

The Twelve Lunar Months Represented By 12 Sarsen Stones

There are twelve full lunar months in every year and these twelve months are represented at Stonehenge by the twelve sarsen stones which are assembled in groups of three to form the four lesser trilithons. Stonehenge timekeepers would have used another marker or seasonal offering to highlight the current lunar month, moving this along at monthly intervals.

The key units of time measurement in all calendars are years, months, and days which unfortunately do not mathematically relate exactly with each other. This has led to a variety of methods for calibrating the year and its seasons. The Stonehenge peoples’ revolving year consisted of twelve lunar months, each of thirty days plus five “intercalary” festival days (six in a leap year). This kept their 360-day lunar calendar synchronized with the sun’s 365.242-day year.

From earliest times a 360-day lunar calendar was used by the majority of ancient peoples, including the Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hebrews, Armenians, Greeks, Romans, Indians, Chinese, Aztecs, and Mayans. The main reason for this choice was that 360 days can be divided into twelve equal months of thirty days which correspond roughly with the moon’s 29.53-day periodicity. Some cultures sub-divided each month into three equal periods of ten days known as “decans”. Small groups of stars associated with each of the 36 decans were painted on Egyptian tombs and coffin lids from 2100 BC. Stellar constellations were also used to identify and name the twelve months of the zodiac. Angles to the horizon were and still are divided into 360 degrees and we count 3,600 seconds in every hour. The tradition of dividing the year into four seasons is very ancient and a 360-day year divides neatly into quarters of three months or 90 days.

The five or six intercalary days were sometimes added at the end of each year (as in Rome), and this may have been the method used at Stonehenge. However, the fact that there were five trilithons suggests an alternative method of dealing with these uncounted days. One uncounted day may have been interposed at each quarter day and one (or two in leap years) at midsummer/midwinter. This would account for the tradition of holding a festival holiday at the start of each quarter – in addition to the midwinter/midsummer festival(s).

The problem of reconciling solar with lunar cycles is still apparent in the variable date assigned by Christians to their Easter festival. This date is determined as the first Sunday after the full moon falling on or after 21st March.

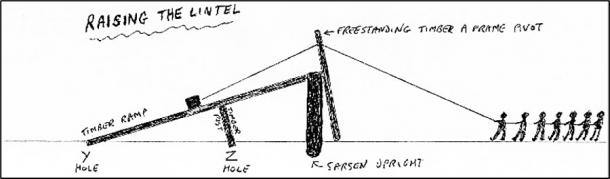

How the lintels were raised to form the top link between sarsen stones. (Author provided)

How were the Stone Lintels Placed on the Sarsen Stones?

The stone lintels that topped the standing sarsen stones were probably hauled up a temporary timber ramp, which was later removed. It is likely that the weight of these lintels pressing down on the ramp and its timber supports were responsible for the two circles of depressions in the soil which are now known as the “Y” and “Z” holes.

The purpose of the circular bank surrounding the complex also requires explanation. Long before the sarsen complex was erected a pole had been driven into the center of the circle and a long leather thong attached to it was then used to mark out two concentric circles of about 86 (282 feet) and 92 meters (302 feet) in diameter, respectively. Substantial posts fixed in holes up to one meter (3.3 feet) deep were located along the circumference of these two circles at regular intervals of about five meters (16 feet). There were 56 posts in the inner circle and a similar number in the outer ring.

These two circles of posts were then connected by substantial timber lintels to form two strong rings. The inner ring of lintels was perhaps about three meters (10 feet) above ground level and the outer ring stood about two meters (6.6 feet) high. Rafters sloping outwards rested radially on these beams to support a roof made from hides, thatch or turf. This provided a framework within which about 56 “apartments” could easily be created (each about five by three meters or 16 by 10 feet), probably using woven hurdles of wattle.

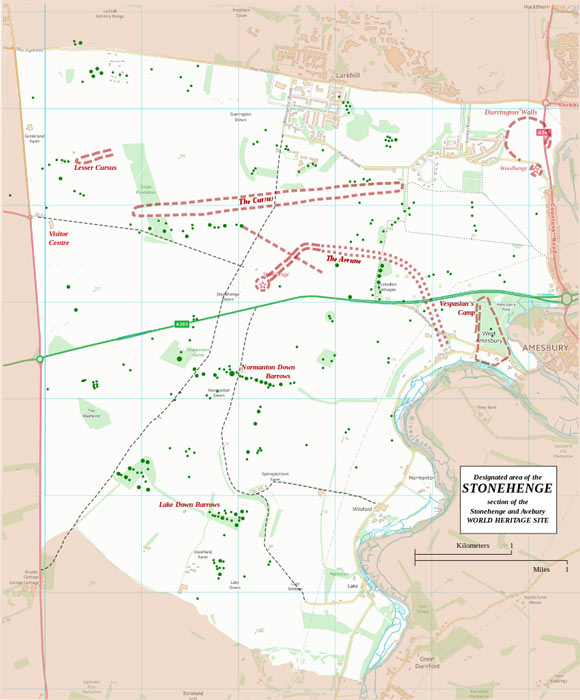

These “apartments” provided accommodation for the Stonehenge timekeepers and their families. This residential function ceased either when the tribe outgrew the circle and moved to larger living accommodation at Durrington Walls and Woodhenge two miles away, or when timekeeping activities ceased. There was plenty of domestic waste in the Stonehenge ditch to indicate that people lived there at one time.

In an early version of “wattle and daub” construction, soil was piled up against the outer wall of the circle to form a protective sloping bank about two meters (6.6 feet) high and six meters (20 feet) wide. In the process a substantial ditch was created which helped to keep the apartments dry. The ditch also served as a communal latrine, accessed through a gap in the circular bank. The occupants of each apartment may have been responsible for the construction of their own quarters, which accounts for minor variations in their dimensions. British archaeologist Aubrey Burl commented that the ditch was not exactly circular but “consisted of a polygon of about 60 straight-sided segments.” This was because the bank and ditch followed the straight back wall of each apartment.

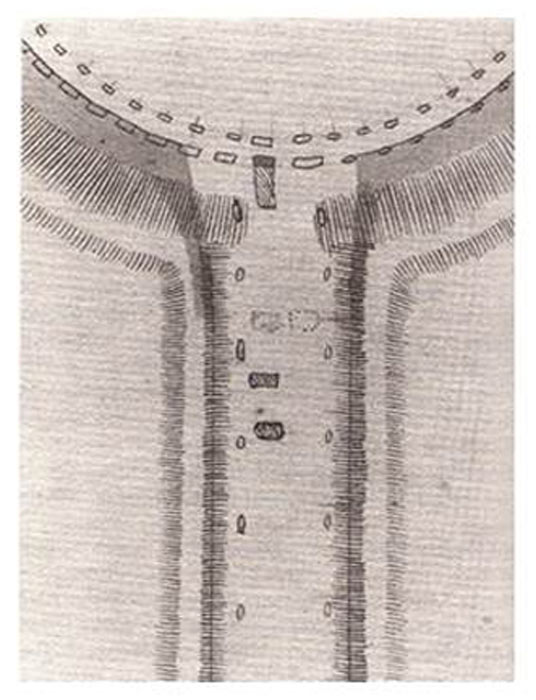

The bank and ditch are still visible today. The inner circle of postholes (known as the Aubrey holes) has been excavated. The outer circle of postholes (now concealed under the collapsed bank) seems to have escaped the attention of modern archaeologists, but William Stukeley’s unpublished 1719 plan of the Stonehenge “Avenue” clearly shows the two concentric circles of postholes.

A diagram of an Aubrey hole, which were also a place where charcoal from adjacent cooking fires and cremations spread over time. (Author provided)

The Aubrey Holes and When The Posts Were Removed

The Aubrey holes have sometimes been described as “cremation pits” but evidence to support that theory is weak. R.S. Newall, who had examined many of the Aubrey holes in 1921, wrote in his 1950 guidebook that most of the “cremations” were not in compact masses deep in the holes as might have been expected, but had been placed quite shallowly at the sides of the holes and had “dribbled down to the bottom.”

Rather than cremation pits it seems likely that ash or charcoal from adjacent cooking fires and cremations had spread out over time and drifted down mixed with soil into the Aubrey holes when their posts were removed. The posts were perhaps redeployed as rollers when the Stonehenge timekeepers hauled enormous sarsen stones to the site. Some archaeologists think that these posts were originally the bluestones which had been laboriously dragged from the Prescelli mountains in South Wales and that were later repositioned within the sarsen complex.

The first group of hunter-gatherers had come to Stonehenge between 8,000 BC and 6,000 BC. Finding plenty of red deer, wild boar, and aurochs they made camp there, digging a large hole about 1.5 meters (5 feet) deep and a meter (3.3 feet) in diameter. In this hole they erected a substantial pine trunk which supported a latticed “maypole” roof anchored to a circle of boulders. When the central pole rotted after some decades the group simply dug a new hole, erected a new tree trunk, and danced under a new “maypole” roof.

Boulders used to anchor the guy ropes of their tent were doubtless redeployed. This cycle was repeated several times over the centuries that followed. Four of these “maypole” post holes carbon dated to 6,000 BC have been found in the former Stonehenge car park, and similar Mesolithic post holes have been found elsewhere. The holes in the old Stonehenge car park are not exactly in a straight line and carbon dating tells us that they were not precisely contemporaneous.

We know from bones excavated at Stonehenge that the tribe were meat eaters, chiefly beef and venison. These animals roamed on Salisbury Plain and were managed by the tribe. Control and capture of half-wild animals is not easy, but Stonehengers used the same simple methods as those employed by farmers everywhere.

The layout of Stonehenge showing the Avenue. (Crown copyright / OGL 3 )

Stonehenge Avenue Transitions to Woodhenge and Durrington

Leading from their circular enclosure the later Stonehengers had raised a bank with fencing or hedging which ran north-east beside the “Avenue” in a straight line from their home for about five hundred meters (1,640 feet). A small group of hunter-farmers could easily drive animals into the angle formed between this hedge and their circular bank. There was a gap between the end of the straight fence and the circular bank where a gate led into a small pen in which animals were probably confined before being killed, flayed, gutted, and roasted for all to share. Burl describes posthole evidence of the stockholding pen as “a puzzlement” for which he can offer no satisfactory explanation.

Over some four centuries the Stonehengers flourished and increased in number until their condominium became seriously overcrowded. It could not readily be enlarged and so overspill settlements were started two miles away which developed into a great circular timber clan house which we now call “Woodhenge,” and “Durrington Walls.”

At Durrington Walls a deep ditch and mile long outer bank surrounded the new tribal residential stronghold which contained many substantial circular timber buildings. Now the tribe had space to further increase and multiply and eventually all residents moved there from the Stonehenge site.

But the tribe did not forget their ancestral home which now became a place of pilgrimage and veneration. Their priest-timekeepers presumably attended daily to update the magnificent stone calendar-temple which they had built there. And the whole tribe probably made pilgrimage to their ancestral home along the ceremonial Avenue for the solstices and quarterly festivals.

Top image: Understanding the Stonehenge calendar is easy if you follow Stephen Childs’ thinking in this article and in his book “Stone Circles Explained.” This image shows sunrise at this ancient site. Source: Gail Johnson / Adobe Stock

By Stephen Childs

“Stone Circles Explained ,” by Stephen Childs, offers some original theories regarding the purposes of stone circles. It is published through Amazon and Kindle and is summarized on YouTube at https://youtu.be/bwiD7NTzJGc

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 28th, 2021

December 28th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: