One of the most controversial organizations in history, the Spanish Inquisition has been poorly understood by the general public. This period of religious persecution, which took place between 1478 and 1834, has historically been shrouded in myth and misconceptions. For despite popular belief, this organization was neither medieval nor exclusively Spanish in nature.

Exploring the Roots of the Spanish Inquisition

Death at the stake was a common form of punishment, dating back to the days of the Roman Empire. With the progressive Christianization of Europe, heresy was seen as the ultimate betrayal –not just to the state but to God himself – and thus a treasonable offense.

The Catholic Church set up the first inquisition, named the Episcopal Inquisition, in order to combat Albigensian heresy which existed at the time in southern France. The Episcopal Inquisition was established through Pope Lucius III’s papal bull entitled Ad abolendam which was issued in 1184 in Verona.

About 50 years later, Pope Gregory IX then escalated the churches authority with the creation of the Pontifical Inquisition, created by issuing the Papal Bull Excommunicamus in the 1230s. As different parts of Europe became increasingly Christian, the ideas behind the inquisition took root in several European Christian kingdoms during the Middle Ages. Within the Iberian Peninsula, the Inquisition only flourished within the Crown of Aragon.

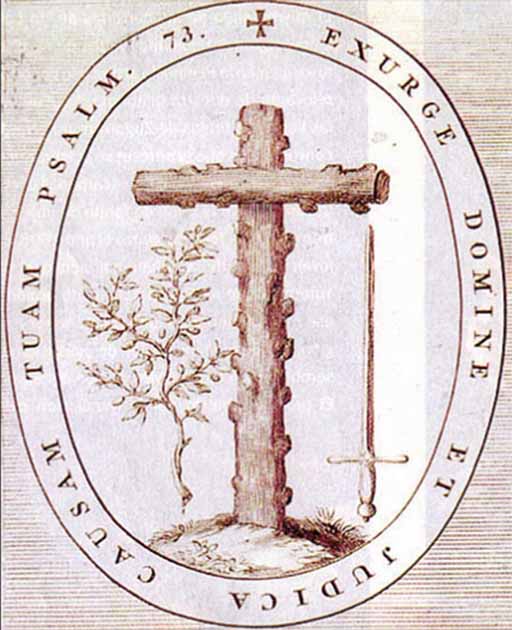

The Shield of the Spanish Inquisition. The sword symbolizes the treatment of heretics and the olive branch of reconciliation with the repentant. Surrounding the shield are the words “Exurge domine et judica causam taum. Psalm 73,” A Latin phrase meaning “Arise, O God, to defend your cause, Psalm 73.” ( Public domain )

“Soft” Repression During the Spain Inquisition

The so-called witch hunt in Spain was far less intense that the “witch mania” taking place in the rest of Europe, although it lasted longer. The Spanish Inquisition was sparked by the widespread witch hunts that developed in Europe in the late 15th century.

These, in turn, were inspired by the Papal Bull Summis desiderantis afectibus issued by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484, as well as the publication of the 1486 Malleus Maleficarum by Kraemer and Sprenger, which bluntly stated: Haeresis est maxima opera maleficarum non credere (which meant “the worst heresy is to not to believe in witches”). A prominent case that came about from these publications was that of Logroño and the famous witches of Zugarramurdi.

In other parts of Europe, the story was very different. In southwest Germany, for example, from 1560 to 1670 AD 3,229 “ witches” were executed according to data from Delumeu; in Scotland, there were 4,400 killed between 1590 and 1680, and in Lorena over 2,000 witches were executed from 1576 to 1606.

In Spain, however, punishment was often less severe. A far more common penalty was known as abjuration of levi, in which the accused was warned, reprimanded, fined, banished for a while (no more than 8 years), and often publicly flogged.

Witches’ Sabbath, or the Coven, by Francisco de Goya. ( Public domain )

Setting the Record Straight: Statistics from the Spanish Inquisition

In fact, during the 400 years of the Spanish Inquisition, from its beginning in 1478 until its abolition in 1834, a total of 130,000 people were judged. Of these, less than 2% – totaling about 2,600 people – were actually sentenced to death.

For a long time, the numbers of accused and those condemned to the stake were confused. The result was the propagation of absolutely absurd and erroneous execution figures, some of which stating that there were more than 100,000 people executed by the Spanish Inquisition.

The acquittal rate during the Spanish Inquisition was surprisingly high. There was a tendency at the time to conclude that the alleged witches had simply been drunk on wine and suffering from drowsiness.

Even in cases where the accused had confessed to witchcraft and a pact with the devil, the Spanish Inquisition warned: “only to proceed if the accused has been seen to commit the crimes, because often what they say they have seen and done happens in their dreams, and to judge what they saw and did as true without having seen the accused in the act will result in inflaming the persecution of persons who are not guilty.”

Auto da fé by Mihály Zichy, which depicts the perceived horrors of the Spanish Inquisition. ( Public domain )

No clear data on the conviction of witchcraft has been kept for all of Spain, except for information in Catalonia and Valencia. In these two places, a clear structure divided into five different phases of witch hunting is observed. Note that the following figures refer to people accused of witchcraft – not convicted, let alone executed.

- During the first phase, ranging from 1560 to 1600, very low figures were recorded, with five-year averages showing less than 8 people.

- The second phase was the height of witch mania in the 1600s, with a total of 60 accused witches in Catalonia and 12 in Valencia.

- The third stage covers the long period between 1610 and 1660, with an average rate of about 15 victims every five years in Catalonia and 12 every five years in Valencia. This highlights the fact that between 1610 and 1620 the Court of Valencia was dedicated to dealing with the problem of the Moors and the subsequent expulsion of Muslims after the Reconquista (meaning the “Re-conquest”).

- The fourth stage covers the decade between 1660 and 1670 when there was a new intensification in witch accusations: no less than 53 in Catalonia in the five-year period between 1665 and 1670.

- The last and final stage involves the return to the figure of less than 20 trials per five years.

One of the most common penalties when the defendant was convicted as guilty was to be whipped while walking the streets. If they were male, they would be stripped naked to the waist, often mounted on a donkey to suffer greater disgrace, and flogged by the executioner with the designated number of lashes. During this journey through the streets, pedestrians and kids showed their hatred and contempt for the heretic by throwing stones at him.

Although the Inquisition was created to prevent the progress of heresy, it also dealt with a wide range of offenses in Spain. Of the total of 49,092 accused in the period between 1560 and 1700, the following offenses were judged: Judaizing (5007); Moors (11 311); Lutherans (3499); Illuminati (149); Superstitious (3750); proposed heretics (14,319); bigamists (2790); solicitations (by priests on parishioners) (1241); insulting the Holy Office (3954); other (2575).

“Condemned by the Inquisition” by Eugenio Lucas. ( Public domain )

Extinguishing the Protestant Reformation with the Spanish Inquisition

During the 16th century, the Spanish Inquisition was revealed as an effective mechanism to extinguish the few outbreaks of Protestantism in Spain. Oddly, most of these “protestant outbreaks” were Jewish in origin.

The main accusations against Lutherans took place between 1558 and 1562 against two Protestant communities of Valladolid and Seville. In these, several crowded auto de fe trials were held, some of them chaired by royals, in which around a hundred people were executed.

Although the trials continued after 1562, the repression was minimized and it is estimated that only a dozen people were burned alive in the years up to the end of the 16th century. This was despite over 200 people going to trial.

The Expulsion of the Jews in Spain in 1492 by Emilio Sala. The painting depicts the Grand Inquisitor, friar Tomás de Torquemada, presenting an edict for the expulsion of the Jews from Spain to the Catholic Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile for their signature. ( Public domain )

The Spanish Inquisition, the Catholic Kings and the Jewish Community

The Spanish Inquisition was not acting directly against the Jewish community, but against Jewish converts. The object of the Spanish Inquisition was to correct errors in the Catholic faith and to combat heresy.

The Catholic Kings were initially favorable of the Jews (apparently Ferdinand had Jewish blood on his mother’s side) and a large group of Jews served in the Spanish royal court. In Castile and Aragon there were about 220 Jewish communities. These Jews depended directly on the king: they were protected by special laws and contributed unique tributes. They were, however, treated as second-class citizens.

As is well known, the Sephardim, a term referring to Jews of Spanish or Portuguese descent, were expelled by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, following a political line adopted earlier by other European kingdoms like England and France. Specifically, it was on 31 March 1492, just three months after the conquest of the Moorish kingdom of Granada, when the Catholic Kings enacted the Alhambra Decree ordering the expulsion of the Jews from all their kingdoms.

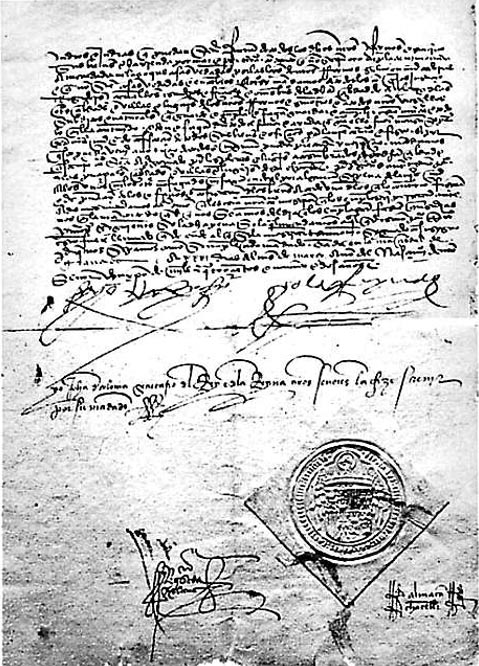

Stamped copy of the Decree of the Alhambra, which ordered the expulsion of all Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. ( Public domain )

Isabel and Fernando were well aware that their decision would not be profitable from an economic point of view, since many Jews were engaged in trade and the financial world. But both religious and social aspects carried a lot of weight in their decision.

They particularly feared the effectiveness of Jewish proselytism or conversion, and they also wanted to avoid mob violence against Jewish communities. In the end they provided two options to Jewish citizens; either baptism or forced exile, the latter being chosen by the vast majority.

The Sephardic Jews in Spain lived in special quarters. The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 urged them to use an external mark to distinguish them from Christians, but the idea was not popular and didn’t catch on throughout the country. The idea had a religious, and not strictly discriminatory, purpose.

The Marranos by Moshe Maimon, depicting a Spanish family’s secret Jewish ritual dinner known as a seder. ( Public domain )

The number of Jews who left Spain is not known, but current estimates by Henry Kamen show that a population of about 80,000 Jews, about half of the total population, chose emigration. Spanish Jews immigrated mainly to Portugal (where they were also expelled in 1497) and to Morocco.

In 1691, in auto de fe trials in Mallorca, 36 Xuetes (Mallorcan Jewish converts) were burned for Judaizing. Throughout the 18th century, the number of converts accused by the Spanish Inquisition was greatly reduced. The last trial against Judaizing was that of Manuel Santiago Vivar, held in Córdoba in 1818.

Now read The Spanish Inquisition: the Truth behind the Black Legend (Part II) .

Top image: Auto de Fe in the Plaza Mayor, an oil painting from 1683 by Francisco Rizi. The painting depicts the ritual public penance carried out by heretics and apostates during the Spanish Inquisition. Source: Public domain

By Mariló TA

This article was first published in Spanish at Ancient Origins en Español and has been translated with permission.

Related posts:

Views: 31

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 9th, 2023

February 9th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: