Melcher de Wind, my distant nephew, has mixed feelings about “herdenkings,” or commemorations. To him, Holocaust Remembrance Day 2021 marks the end of a year full of commemorations of the Holocaust and his beloved father, Eddy de Wind, who wrote his memoir in real-time during the 16 months he spent in Nazi captivity during World War II just because he was a Jew.

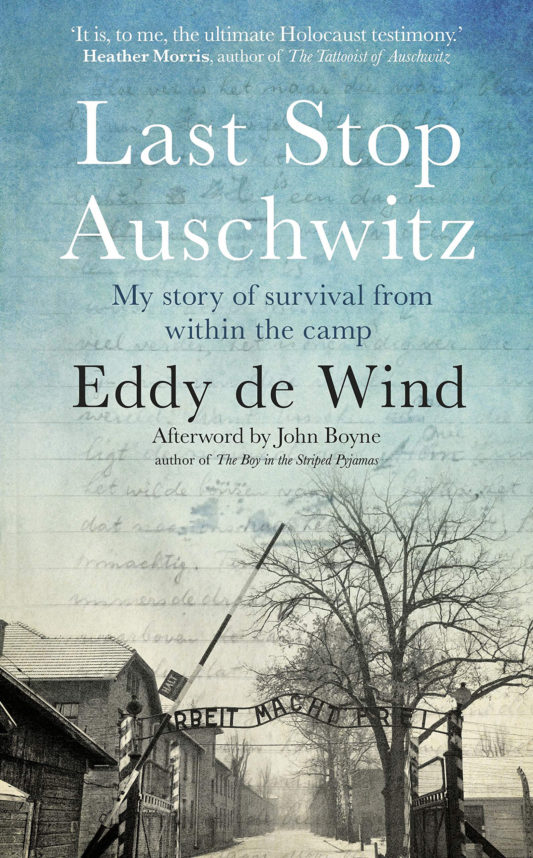

One year ago, Melcher’s family published “Last Stop Auschwitz: My Story of Survival from Within the Camp,” a book of those memoirs translated for the first time into English and now into 30 other languages. For the family, this Holocaust Remembrance Day will be a time to reflect on the emotions, doubts and heart-searching they have experienced in deciding to publish the book and, subsequently, in attending “herdenkings.”

“Last Stop Auschwitz” is probably the only Holocaust account written “in situ,” from the belly of the Nazi beast, while the horrors were still fresh in de Wind’s memory and psyche. The book was published twice in Dutch and only in limited numbers — once immediately after the war and again nearly four decades later. At both times of publication, the book did not receive the publicity and attention the unprecedented work so rightly deserves.

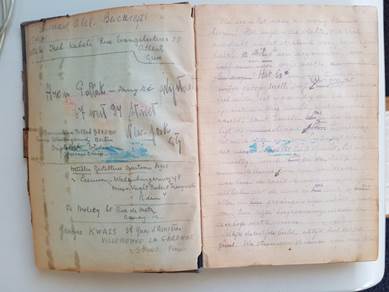

Melcher de Wind recalled to me how, as a little boy, he saw his father’s manuscript “tucked away between other books.” He leafed through it once, never realizing the significance of the family heirloom.

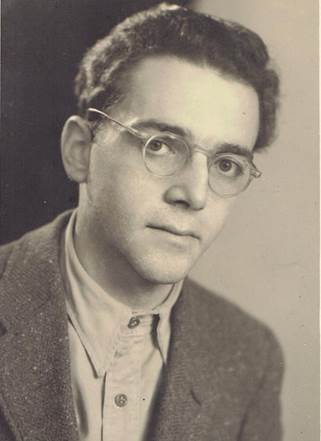

Although he penned his memoirs in the camp, Eddy de Wind never set his story completely aside. On his deathbed in 1987, de Wind thought he was back in Auschwitz. His son recalled, “We — our mother, my brother, my sister and I — didn’t know what to do with his emotionally-charged legacy.”

That continued to be so for the next 30 years, until, in 2018, the “Eindstation Auschwitz” manuscript became part of prominent exhibits at international Holocaust exhibitions in Madrid and elsewhere, drawing intense attention.

The book has since become one of the defining accounts of the atrocities and inhumanities perpetrated by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

Publication of the book was a family project, led by Melcher de Wind. “No easy task,” de Wind said to me. “At first, it led to a lot of tension between us, but it also gave us a reference point and a new, mutual goal that ended up bringing us closer together.” He added, “The process of publishing the book taught me a lot about the role my father’s past had played in my life, finally helping me to cast off the ‘curse’ of Auschwitz. Essentially, it was a commemoration that would last more than a whole year.”

De Wind is referring to the whirlwind of obligatory interviews, book fairs, book-signings, press conferences and Holocaust commemorative events that followed the success of his father’s book this past year.

He remembers attending a Holocaust-related commemoration with his father several years after his father’s return to the Netherlands from Auschwitz in 1945. “The emotions and unspoken reproach made the commemoration exhausting for my father, and he was very confused,” De Wind explained to me. “Once home, he withdrew into himself, remaining distraught for days…”

De Wind told me that his father’s experiences at Auschwitz, along with the murders of his father’s family and friends, remained an open wound for him — memories too real, too recent, too raw and too painful to be assuaged by commemorations.

De Wind told me that his father’s experiences at Auschwitz remained an open wound for him.

“My father’s incapacity to come to terms with the sorrow often led to intense anxiety and panic attacks in the days leading up to a commemoration,” he said. “At the gatherings themselves, I was preoccupied with trying to keep an eye on him. Was he managing? Could he handle it, or was he about to panic?”

Melcher attributed his own dislike of commemorations to seeing how much his father suffered at such events and to his own perception of a certain amount of shallowness at such gatherings. “People attend and feel remorse, but when they go home afterwards, they can live on as if nothing has happened,” he said.

However, publishing his father’s book forced de Wind to come face-to-face with his doubts and anxieties. For example, last year, de Wind — who lives in Amsterdam — finally visited Auschwitz, a place that for him had always been “an absolute no-go.”

A place, de Wind explained, where his father’s family was transported to by force and then gassed like infected animals. A place where his father barely survived after suffering the deep wounds that burdened him throughout the rest of his life. A place where his father wrote the book in a notepad he had found among Schutzstaffel (SS) supplies, a book that would bring Melcher to Auschwitz more than 60 years later.

During that portentous visit to the Nazi death camp, de Wind saw the infamous barracks, cringed at the ruins of obscene gas chambers and found Auschwitz “empty, a dead museum where it’s hard to imagine the terrible things that took place there.”

He also realized that one of the most memorable aspects of his father’s book is “the way it gives you a chance to really visit Auschwitz…It guides you through the pain, the fear, the arbitrariness and sadism of the place but also through the solidarity and hope that kept the prisoners going.”

De Wind now realizes that his visit has “humanized’ Auschwitz for him. Being able to walk around Auschwitz without intense fear was a victory for him. “My father had survived the camp; he had worked there as a doctor for months after it was liberated, and he had written his book there. More than ever, I felt incredibly proud of him,” de Wind said.

The Auschwitz visit has had a “liberating effect” on de Wind, just as several other “herdenkings” would have. But memorials continue to be a delicate balancing act between competing emotions — despair, anger and hope.

For example, de Wind cited an exchange he had with his father when he was only 16. Melcher had asked his father, “Did anyone ever survive the gas chambers?” His father replied, “There was a group of Hungarian children who came out of the gas chamber alive.”

Melcher felt enormous relief. “So, it was true. It wasn’t all darkness; there is always hope,” he thought. But his father continued: “Afterwards, they were burnt alive.”

De Wind also told me about a more recent conversation. After an event in Budapest for “Last Stop Auschwitz,” a very old Hungarian lady came up to him. She told him how, in the late summer of 1944, she and other Hungarian Jews were herded to the gas chambers immediately after their arrival in Auschwitz. But after a few minutes, the doors opened again, and some of the prisoners were taken back to the camp. She was one of them.

Stunned, de Wind asked, “So you survived the gas chamber?” “Yes, something went wrong, and we were spared,” the survivor answered.

“Whenever I think back on that moment,” de Wind said, “I am overcome by emotion. I don’t know who the woman is, but in my mind, I have come to love her. Her story encourages me and makes me realize that commemorating pain is not enough. More than anything else, we must look to the future with hope.” “Herdenkings,” then, can be inspirational and liberating after all.

This particular “herdenking” of 2021 can only reinforce humanity’s call for “Never Again.”

Dorian de Wind is a retired U.S. Air Force officer, born in Ecuador and educated in the Netherlands. He now makes Texas his home.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 27th, 2021

January 27th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: