From Wear’s War

Fate of German Children in Eastern Europe

One of the great tragedies of the 20th century was the forced expulsion of ethnic Germans from their homes after the end of World War II. One estimate of the Germans expelled runs to 16.5 million: 9.3 million within the 1937 Reich borders and 7.2 million outside.[1]

One of the great tragedies of the 20th century was the forced expulsion of ethnic Germans from their homes after the end of World War II. One estimate of the Germans expelled runs to 16.5 million: 9.3 million within the 1937 Reich borders and 7.2 million outside.[1]

German children in Eastern Europe suffered major hardships and deprivations prior to and during the expulsion process. From August 1945, the Czech government allocated to German children under the age of six only half the allowance of milk, and less than half the allowance of barley, allocated to their Czech counterparts. German children received no meat, eggs, jam, or fruit syrup at all, these being allocated entirely to children of the Czech majority.

One example of the prevailing mood in Czechoslovakia toward German children was expressed by the Prague newspaper Mladá Fronta, which ran a ferocious campaign against British proposals to provide a temporary haven for thousands of starving German children during the winter of 1945-1946. When an announcement was made that the scheme would not go ahead, the newspaper’s headline read:

British Will Not Feed Little Hitlerites: Our Initiative Crowned With Success.”[2]

In the Polish Recovered Territories, food ration cards were progressively withdrawn from the entire German population. Like their parents, German children found that they were entitled to no rations at all. The head of the Szczecin-Stołczyn Commissariat thus proudly reported that since the end of November 1945, even German children under the age of two had their milk allocation withdrawn from them.

Polish laws designed to protect German children were typically never enforced. For example, a directive issued in April 1945 by the Polish Ministry of Public Security specifying that nobody under the age of 13 was to be detained was never followed. More than two years later, the Polish Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare was complaining that the regulations against imprisoning children in camps continued to be “completely ignored.” German children were illegally detained in Polish internment camps as late as August 1949.[3]

German children experienced the worst conditions in the detention centers. Přemsyl Pitter, a social worker from Prague, quickly found as he visited the Czechoslovak detention centers that the overwhelming majority of those who needed his aid were ethnic Germans. At a makeshift internment camp in Prague, Pitter discovered at the end of July 1945 “a hell of which passers-by hadn’t the faintest notion.” More than a thousand Germans, the great majority women and children, were “crowded together in an indescribable tangle. As we brought emaciated and apathetic children out and laid them on the grass, I believed that few would survive. Our physician, Dr. E. Vogl, himself a Jew who had gone through the hell of Auschwitz and Mauthausen, almost wept when he saw these little bodies. ‘And here we Czechs have done this in two and a half months!’ he exclaimed.” Officials of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) found that the conditions at other Prague camps were no better.[4]

The youngest German children were most vulnerable to the conditions in the detention centers. Their undeveloped immune systems and lack of physical reserves left them particularly vulnerable to starvation and its attendant diseases. A credible account by a female detainee at Potulice in Poland recorded that of 110 children born in the camp between the beginning of 1945 and her eventual expulsion in December 1946, only 11 children were still alive by the later date. A high rate of infant mortality in the camps was also caused by numerous cases in which German children were denied medical care because of their ethnicity.

The youngest German children were most vulnerable to the conditions in the detention centers. Their undeveloped immune systems and lack of physical reserves left them particularly vulnerable to starvation and its attendant diseases. A credible account by a female detainee at Potulice in Poland recorded that of 110 children born in the camp between the beginning of 1945 and her eventual expulsion in December 1946, only 11 children were still alive by the later date. A high rate of infant mortality in the camps was also caused by numerous cases in which German children were denied medical care because of their ethnicity.

Investigations by the ICRC found high rates of infant mortality attributable to malnutrition to be widespread in Czechoslovakia. When the ICRC visited a detention center in Bratislava at the end of 1945, it found that every one of the emaciated infants and children was “suffering from hideous skin eruptions” and that conditions were “in general so desperate that it is difficult to find words” with which to comfort the detainees. A journalist from Obzory, who visited one of the Prague detention centers in the autumn of 1945, acknowledged that “mortality has increased to a horrifying degree” among the children. The journalist attributed the high mortality among the infants to the complete absence of infant formula and the fact that the majority of nursing mothers were too emaciated to breastfeed their newborns.[5]

Authorities generally did little to shield children from the harsher aspects of camp life. Germans in Czechoslovakia typically became forced laborers on their 14th birthday, with some districts requiring labor services of those aged 10 or above. At Mirošov in Czechoslovakia, the definition of “adult” for forced labor consisted of all inmates above six years of age. Children of 10 years of age and above were also routinely used as forced laborers in Yugoslavia.

In September 1945, the ICRC complained that in the Czechoslovak camps the young male guards treated detainees with “the utmost cruelty,” with widespread beatings of children as well as adults. Many children were also subject to psychological abuse, and some children were compelled—as at Kruševlje in Yugoslavia—to witness their parents’ torture or execution at the hands of camp guards.[6]

In September 1945, the ICRC complained that in the Czechoslovak camps the young male guards treated detainees with “the utmost cruelty,” with widespread beatings of children as well as adults. Many children were also subject to psychological abuse, and some children were compelled—as at Kruševlje in Yugoslavia—to witness their parents’ torture or execution at the hands of camp guards.[6]

The Western Allies did not intervene to help ethnic German children in Eastern Europe since they regarded all Germans as perpetrators of World War II. The policies of the Western Allies and the expelling nations were a violation of their subscription in 1926 to the International Declaration of the Rights of the Child, which stipulated that children were to “be the first to receive relief in times of distress” without taking into account “considerations of race, nationality or creed.”

German children were also denied aid from international relief agencies like UNRRA and the International Refugee Organization (IRO) as a matter of policy. Even the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) maintained a discriminatory stance against German children, assigning priority to the children of “victims of aggression” in the provision of aid. The plight of children in the expelling countries was additionally worsened by the expropriation of German religious and charitable organizations, which caused German children in orphanages and facilities for handicapped children to lose their homes. In the long run, the only hope for most German children in the expelling countries was their expeditious removal to Germany, in-spite of the difficult conditions they were likely to encounter there.[7]

Warning: Graphic content, not suitable for children.

About Germany’s War

Related Articles:

History’s Most Terrifying Peace: Allied Run Concentration Camps

How Many Genocides Can Germany Survive: Part 1 and Part 2 Evidence Of Deliberate Mass Murder

The 2 Million: The Rape of German Girls & Women – Red Army, French & American Occupied Territory

ENDNOTES

Image: German child refugees from Poland

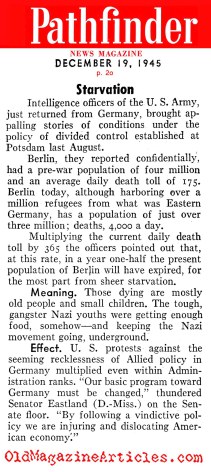

Images: Little Girl With Ribbon in Her Hair 1945 and News-article

[1] MacDonogh, Giles, After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation, New York: Basic Books, 2007, p. 162.

[2] Douglas, R. M., Orderly and Humane: The Expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012, pp. 233-234.

[3] Ibid., pp. 234, 236.

[4] Ibid., pp. 234-235.

[5] Ibid., pp. 234, 238-239.

[6] Ibid., pp. 234, 236-238.

[7] Ibid., pp. 240-241, 244.

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/righteous-victorious-allies-starved-abused-enslaved-german-children-eastern-europe/

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 3rd, 2017

December 3rd, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: