Rapa Nui, the original name for Easter Island, is most famous for its giant monolithic moai statues. Located 3,512 km (2,182 mi) off the coast of Chile, Rapa Nui has suffered a history of constant exploitation and mistreatment by outsiders. This has included the plunder of its ancestral remains and sacred objects which can now be found scattered in museums around the world, in cities such as Berlin, Brussels, London, Paris, Oslo, New York and Santiago. But now, the people of Rapa Nui are celebrating the return of one of their ancient moai statues after 152 years at the Natural History Museum of Chile in Santiago.

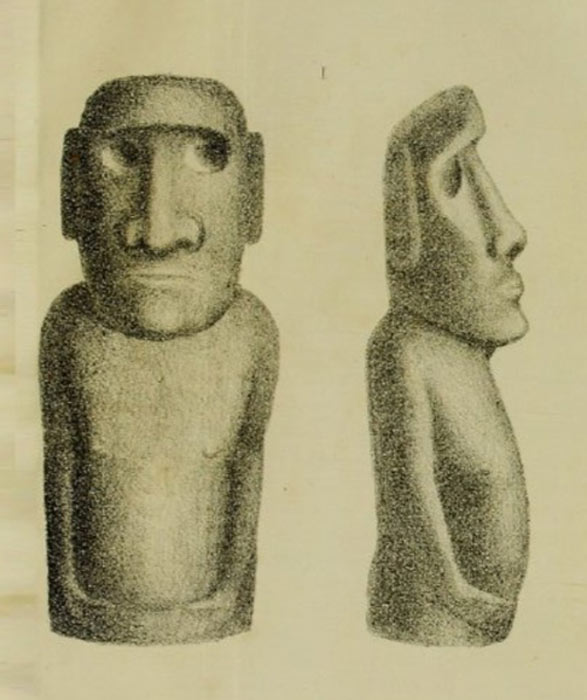

Drawing of the moai from the Chilean corvette O’Higgins expedition by Rodulfo Philippi circa 1873. ( Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile )

Bringing the Moai Back from the Chilean Mainland

In recent years, the Rapa Nui have started a coordinated effort to repatriate these sacred artifacts as part of their Ka Haka Hoki Mai Te Mana Tupuna Repatriation Program. These objects include giant moai statues , believed to be the aringa ora , or living faces of the ancestors. For the Rapa Nui the moai are not only representations of the spirits of their ancestors, but also considered living incarnations of the same, as well as vessels of ancestral energy, known as mana, needed to protect the islanders. In fact, the movement for repatriation is inextricably linked to the movement to attain civil rights for the Rapa Nui.

While Chile annexed the island in 1888 due to its strategic location, it was in 1870 that Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bournier, a polemic French mariner of dubious repute looking to establish a French protectorate on Rapa Nui , gifted a moai to the Chilean corvette O’Higgins. Under what authority is hard to fathom, but as a result the moai was taken to Santiago later that year, and it was here, at the Natural History Museum of Chile (MNHN), that it became a central part of a permanent exhibition on Rapa Nui culture, cataloged with the inventory number 3208.

At 150 cm (59 in) tall, and weighing 715 kg (112.6 st), the moai was made of basalt rock. Experts still do not know the name of the person it represented, a fact in part attributed to the massive loss in cultural knowledge accompanying what has been termed a genocide caused by slavery, disease and cruelty in the recent history of the island.

Cristian Becker, Chief Curator and Scientist at the MNHN, together with Consuelo Valdés, Minister of Culture, Arts and Heritage. ( Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile )

For Cristian Becker, the Chief Curator at the MNHN, the repatriation of the moai is a significant step charged with symbolic value. In fact, the repatriation of this particular moai from Santiago is especially important.

“During international conversations about the repatriation of artifacts from abroad, one of the points raised is why in our own country, Chile, there are still Rapa Nui objects in museums,” explained the filmmaker Leonardo Pakarati, director of the 2015 documentary The Spirit of the Ancestors . “For that reason, we have aimed to start repatriation ‘at home’, and repatriate some of the ancient moai from the continent.”

The process of returning the moai from the MNHN began back in 2018 when a group of Rapa Nui organizations, including CODEIPA, the Council of Elders and the Ma’u henua Indigenous Community, lodged a formal request during a visit to Santiago, Chile. “When we visited we promised him [the moai] that we would bring him home, although we didn’t know when or how,” explained Anakena Manutomatoma, the president of the CODEIPA Development Subcommittee.

In February 2019, the Minister of Culture Consuelo Valdés confirmed Chile would return one of three moai housed at the MNHN. “For the first time, a moai will return to the island from the mainland,” said Valdés in The Guardian when the moai began its journey back to Easter Island in February 2022 to a backdrop of farewell celebrations performed by members of the Rapa Nui community in Santiago.

The moai leaving the National History Museum of Chile in Santiago. ( Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile )

Why is it Important the Moai Come Home?

The importance of the moai and their meaning to the Rapa Nui was clarified in the touchingly intimate documentary The Spirit of the Ancestors , which tells the story of the stolen moai (particularly the Hoa Hakananai’a moai which currently resides at the British Museum in London) and its meaning for a selection of Rapa Nui characters and their modern-day voyage to film it, in the face of polite resistance from the museum.

Stolen and removed from the island in 1868, Hoa Hakananai’a was brought to the United Kingdom as a gift for Queen Victoria . What made this moai special is that it presided at Orongo over the yearly Birdman competition , where contestants from competing tribes battled to obtain the first sooty tern egg of the season from the Motu Nui islet. This event decided which tribal chief would rule over the island for the coming year. The moai itself includes petroglyphs associated with this birdman cult on its back.

A symbol of changing times, the Hoa Hakananai’a moai is particularly important as it represents the end of the ancestor cult and the beginning of the new Birdman cult era. Alongside Catholic missionaries the meddling Frenchman, Dutrou-Bournier, struck again, gifting the Hoa Hakananai’a moai to a British survey ship, the HMS Topaze, because its function as part of the Birdman cult eclipsed their desire for power on the island.

Leonardo Pakarati presiding a karanga ceremony at the foot of the Hoa Hakananai’a moai at the British Museum in London. Screenshot from the documentary. ( The Spirit of the Ancestors / Mahatua Producciones )

“I picture the Hoa Hakananai’a crying to come back,” stated abuela Noe, one of the main characters in the documentary. But, how can a statue cry, you may ask? “While the Western world understands the moai to be stone sculptures, for us they have a far more profound cultural meaning,” explained Leonardo Pakarati over the phone. “In the past they were important because the spirits of our ancestors lived inside these statues, while today they are a way for us to rebuild a past which we lost under duress.”

For the Rapa Nui, these statues are not simply cultural assets, they are ancestors tasked with protecting their people and they should never have left the island. So strong is this thinking, that in November 2018, representatives of the community, including the President of the Council of Elders Carlos Edmunds and the Minister of National Assets, Felipe Ward, began a formal dialogue with the British Museum for the return of the Hoa Hakananai’a statue.

The original ahu, or platform, belonging to the Hoa Hakananai’a moai. Screenshot from the documentary. ( The Spirit of the Ancestors / Mahatua Producciones )

Understanding the Concept of Mana

This battle for repatriation is part of a far deeper belief system. “We need this mana [energy] returned to Rapa Nui,” decried Pakarati during a karanga ceremony which took place at the foot of the moai in the British Museum in London and was depicted in the documentary. “Hoa Hakananai’a means ‘the friend who made us happy’. We need to be happy again.”

Mana is a complex term to understand and is inextricably linked to the worldview of the Rapa Nui. Believed to be a spiritual life force or energy, mana exists in people, spirits and within inanimate objects. Islanders believe that due to their tragic history, and the theft of their cultural heritage, the mana energy is not balanced on Easter Island, evidenced by the lack of unity amongst its residents.

Keep in mind that although annexed in 1888, the Rapa Nui were only accorded their rights as citizens of Chile in 1966, just a few years before Pinochet began his dictatorship, taking away the rights of all Chilean citizens. Before that, the Rapa Nui had essentially been reduced to slavery by the Williamson-Balfour Company who leased the island from Chile as a sheep farm and confined the native residents to a small portion of the island in utter poverty. “Historically, our association with Chile hasn’t gone very well for us,” stressed Leonardo Pakarati.

The thinking is that should the stolen moai, ancestral remains and other sacred objects return, they would bring with them their lost mana, or energy, and its ability to protect Rapa Nui. “We all hope that this event will finally achieve what we want, which is to stabilize the mana in order to conquer something that we have always treasured – happiness,” clarified Pakarati.

The moai from Chile arriving at Easter Island in March 2022 and (bottom right) Anakena Manutomatoma during the moai welcome ceremony. ( Paula Rossetti )

The Arrival of the MNHN Moai to Easter Island

Having been completely closed off to the world for over two years due to the pandemic, on the morning on the 8th March 2022 a group of residents met at the Hanga Piko docks to welcome the moai back to Rapa Nui and accompany it to its new home at the Padre Sebastián Englert Anthropological Museum . “What has happened is so important for us that I’ve smiled all day,” laughed Anakena Manutomatoma, who took part in the celebrations.

The moai was welcomed by a series of traditional umu or curanto celebrations, a way to give thanks, cook and share food, accompanied by singing. “One curanto took place in Santiago when the moai left the museum to bless his journey home, and another when he arrived in Rapa Nui to bless his arrival, to bless him for once again breathing his air, feeling his wind, watching his ocean and seeing his people,” explained Manutomatoma. The final curanto took place when the moai reached the museum.

Welcome ceremony for the moai on the 8th March 2022. ( Paula Rossetti )

As explained on the Rapanui Museum website , the moai’s journey back to Rapa Nui was anything but easy, requiring the construction of a special structure to get it down from the second floor of the MNHN museum in Santiago, and a special packaging and base to avoid any damage on its way home. It left the museum on the 21st February, was transported to the Chilean port of Valparaiso from where it began its journey by boat on the 28th of the same month. On arrival to Rapa Nui, an island with no port, it then remained on board until conditions allowed for it to be transferred and taken to land on a smaller vessel.

In reference to its new home at the museum, which is managed by the Chilean Ministry of Culture, Arts and Patrimony, there is some skepticism. “The moai was not made to be in a museum,” explains Pakarati. “It was made to be on its ahu (platform), under the sun, under the rain, exposed to the smoke of the campfire.” The community is going to continue discussions to decide on its final resting place.

A member of the Rapa Nui community welcoming the moai back to the island. ( Paula Rossetti )

What’s Next? The Return of the Moai

“For us, the return of this moai is like a door opening so that all the rest of the moai located around the world can return,” highlighted Carlos Edmunds, President of the Elders Council, in an interview. The Kon-tiki Museum in Oslo, Norway, plans to return thousands of artifacts, including human bones, collected by the explorer Thor Heyerdahl when he visited Easter Island from 1955. They signed an agreement in 2019 with officials from Chile’s Ministry of Culture in Santiago to this end.

Islanders also hope to repatriate two more moai from the mainland, currently housed at Viña del Mar and La Serena. Meanwhile, negotiations to return the Hoa Hakananai’a moai from the British Museum continue. After talks in both London and Rapa Nui, and a commitment to develop “a long-term relationship with the community of Rapa Nui,” the British Museum stated that the presence of the Hoa Hakananai’a moai in London “increases public understanding of the history of Rapa Nui, its people’s artistic achievements past, present and future, and the challenges faced by the community today.” In other words, for now there are no concrete plans for its return.

Speaking in The Spirit of the Ancestors , Isabel Pakarati, a master craftswoman recognized as a Living Human Treasure by the Chilean State, put it succinctly:

“You think they don’t cry when they’re away? The things the scientists have taken away from here, it’s important they send them back to their origins. Because that mana is here. And it’s more important for us to teach that to our children. Do you understand?”

But, for now the Rapa Nui are celebrating the return of the moai . “We thank God for opening the doors, for opening hearts and for allowing us to celebrate the return of our ancestor to his land,” concluded Manutomatoma. “We are thankful to be able to savor his presence and that he is here taking care of all his descendants. We will leave this earth soon, but he will remain standing to carry out his work.”

Top image: The return of the moai to Rapa Nui from Chile. Source: Paula Rossetti

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 11th, 2022

March 11th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: