The Spider Woman of Teotihuacan continues to be one of the most mysterious figures of ancient Mexican culture. She is also known as the Great Goddess, but since 1983 Spider Woman has become the most popular reference to her. The Spider Woman is depicted on several murals at the pre-Columbian site of Teotihuacan and “she” is unique to this city and culture only. The murals were only discovered in the early 20th century and archaeologists are still unable to say for certain who she is. In recent decades, several different experts have offered their ideas about the Spider Woman’s identity.

The Spider Woman, known also as the Great Goddess, is one of the great mysteries at the site of Teotihuacan. The name of this site, which translates from Nahuatl to mean “City of the Gods.” As a matter of fact, this was the name given to the site by the Aztecs when they discovered the city in the 1400s. By then, the city had been long abandoned, which means that much of the city’s history and culture before the arrival of the Aztecs has been lost. We do know, however, that prior to the rise of the Aztecs, Teotihuacan was the largest and most important city in central Mexico . According to some estimates, the city, at its height, supported a population of between 125,000 and 200,000. If these estimates are correct, it would make Teotihuacan one of the largest cities in the world during its heyday.

Stunning view of Teotihuacan. (SimoneGilioli / Adobe Stock )

A Summary Of What We Know About Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan is located about 30 miles (50 km) northeast of present-day Mexico City . The site was settled as early as 400 BC. In the centuries that followed, however, Teotihuacan remained a small settlement, and did not experience significant growth.

It was only towards the end of the first millennium BC that Teotihuacan began its rise as a major city. According to one theory, it was around this time that refugees from Cuicuilco, a city that was destroyed by a volcanic eruption, arrived, and settled in Teotihuacan. The theory goes on to suggest that it was these refugees who contributed to the massive building period that makes Teotihuacan so famous today. Supporters of this theory argue that distinct characteristics of various cultures, including Maya, Zapotec, and Mixtec, can be identified at Teotihuacan. Alternatively, it has been suggested that it was the Totonacs, a tribe from the east, who built Teotihuacan. A third theory, is that the city was built by the Toltecs. This theory is based on colonial texts, and has since been debunked, as the Toltecs flourished several centuries after the demise of Teotihuacan.

Teotihuacan flourished for hundreds of years but the city fell around 750 AD as a result of civil war or a violent uprising. The city was not completely abandoned after this event, but much of it fell into ruin. As mentioned earlier, the city was re-discovered by the Aztecs during the 15th century AD.

Today, Teotihuacan is an archaeological site famous its massive monuments, especially the Temple of the Feathered Serpent (or Quetzalcoatl), the Pyramid of the Sun, and the Pyramid of the Moon. The Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon are the site’s largest and second largest monuments respectively.

Interestingly, between 1905 and 1910, restoration work was carried out on the Pyramid of the Sun. Unfortunately, the work was hastily organized, and the architect, Leopoldo Batres, arbitrarily added a fifth terrace level to the monument. Moreover, many of the original facing stones were removed during that restoration work.

In any case, the three buildings are connected by the Avenue of the Dead, which was believed to be lined with tombs. Today, archaeologists believe the avenue was lined with regal residences.

The Avenue of The Dead leading to the Pyramid of the Moon in the ancient city of Teotihuacan, the unique and only “home” of the mysterious Spider Woman. (Ricardo David Sánchez / CC SA-BY 3.0 )

The Archaeological Excavation History Of Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan was first excavated in 1884 by archaeologists. However, the first systematic surveys of the site were in the 1960s and 1970s. In the decades that followed, archaeologists continued to work at Teotihuacan, adding to our knowledge about this ancient city. In 1987, Teotihuacan was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In spite of the site’s significance and international recognition, Teotihuacan (especially the areas farthest from the city’s core) faces a number of threats, including the encroachment of modern towns, roads, highways, and a military base.

The archaeological investigations of Teotihuacan have brought to light many well-preserved murals. These important artifacts are regarded as one of the major sources of historical information for understanding the city’s religious and social organization, which are today only partially understood. This is largely because the people of Teotihuacan did not leave behind any written records. The murals are found throughout the site on the walls of so-called “apartment compounds.” These multi-story buildings were used for residential purposes and indicate just how big the population of Teotihuacan was.

Some of the Teotihuacan murals (70 fragments in total), known as the Wagner Murals, are part of the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. These murals were illegally removed from Teotihuacan during the 1960s, and the process was completely undocumented. Rene Millon, an archaeologist from the University of Rochester, managed to track down the specific location from where the murals were removed, an area containing two or three palaces, and aptly named the “Square of the Ransacked Murals.” All these “stolen” murals were acquired by Harold Wagner, an eccentric San Franciscan architect who lived in Mexico for some time. When Wagner died in 1976, his collection of Teotihuacan murals was donated to the museum.

Since then, the museum initiated the Teotihuacan Mural Project, and they have published some information about where the murals came from, and how they were made. The murals were created on the existing thinly plastered walls as follows:

“They consist of a volcanic ash aggregate which includes clay and pottery shards. This ground is covered with a very thin coating of lime (2 mm) which, in contrast to the coarse backing material, is extremely smooth. The lime layer was painted in fresco, very similar to that technique employed by the Italians. Some of the murals appear to have been burnished, possibly with a smooth stone.”

Although red is the main color used in the mural paintings, other colors, such as blue, green, and yellow, black, and white, were also used. An article published in 1986 identified the pigments used to make the paints. The red paint was made from a local specular haematite, the green, malachite, the yellow, limonite, the black, charcoal, and the white, calcite. The results of the composition for the blue paint is still inconclusive.

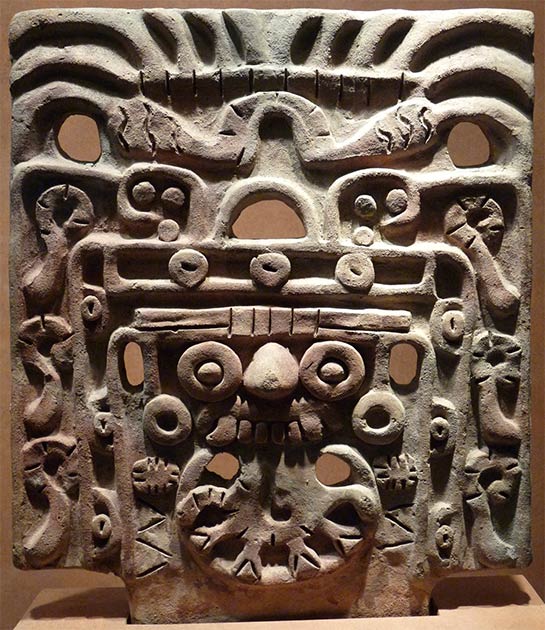

Face mask of Tlaloc or the Storm God on display at the National Museum of Anthropology and History, Mexico City. (El Comandante / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

In terms of style, the animal and deity figures have been described as “flat and linear.” Animals included coyotes, owls, and jaguars, which feature prominently. And two particular deities, the Storm God (known also as Tlaloc amongst the Aztecs) and the Great Goddess (Spider Woman) are depicted frequently in the murals. Like his Aztec counterpart, the Storm God is nearly always depicted in profile, and may be identified by his characteristic face mask and the lightning bolt in his hand. The Great Goddess, on the other hand, seems to not have any Aztec counterpart to compare with.

The Spider Woman Name Has Only Been Popular Since 1983

As already mentioned, the term Spider Woman and Great Goddess refer to the same deity, an indication of the confusion among experts regarding this magnificent being. The image of this mysterious figure first drew attention in 1942, when it was discovered as part of a series of murals in Teotihuacan’s Tepantitla compound. Despite the two names given to her, nobody knows how she was referred to by the ancient inhabitants of the city. As a matter of fact, she was only called the Spider Woman in 1983, by the archaeologist Karl Taube. The figure was associated with the spider thanks to her nose pendants with “fangs,” one of the two features that appear in every depiction of the Spider Woman that we know of. The other is her elaborate feather headdress. Other features found in paintings of the Spider Woman include mirrors and spiders.

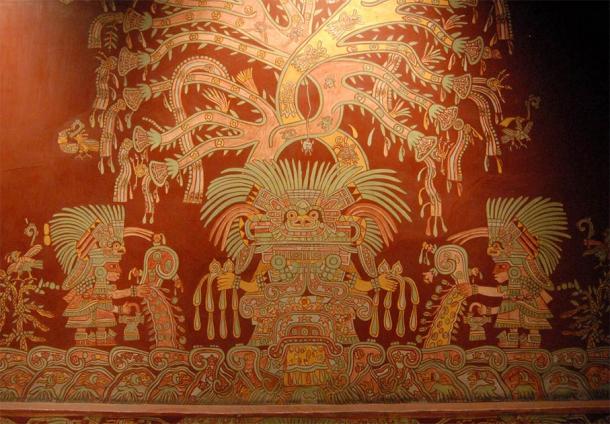

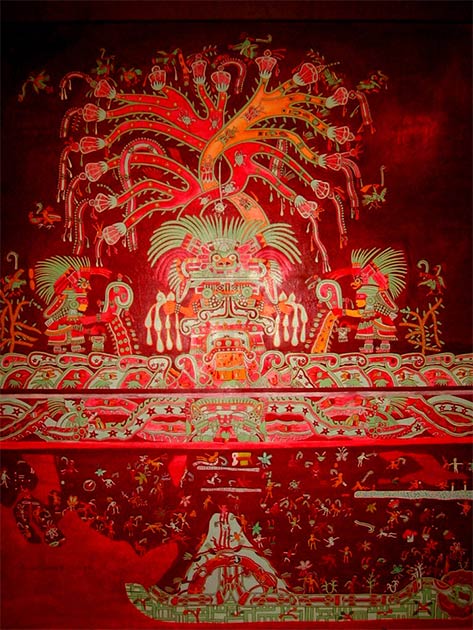

A reproduction of one of the murals depicting the Spider Woman or Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, from the Tepantitla apartment complex, on display in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City. Source: Thomas Aleto / CC BY 2.0

Unlike the Storm God, the Spider Woman is always depicted from the front. Additionally, she is often shown with open arms, and in the process of giving gifts. One interpretation is that the Spider Woman is supposed to be an agricultural goddess who was responsible for maintaining the fertility of the land. In one depiction of the Spider Woman, the “Great Goddess Mural of Tepantitla Patio 2,” the figure is part of a larger mural. Whilst the Spider Woman occupies the top half of the mural, the bottom half is occupied by what is thought to be the citizens of Teotihuacan. When considered as a whole, the mural may be interpreted as depicting the Spider Woman as a protectress of the city’s inhabitants. Nevertheless, the are various questions surrounding this interpretation. For instance, it is unclear whether the bottom half of the mural is supposed to depict the realm of the living or the realm of the dead. If it were the latter, the Spider Woman could be considered to be a chthonic deity.

The debate surrounding the Spider Woman has continued long after her images were first discovered, a sign that scholars are still fascinated by this mysterious figure. In 2006, for instance, an article entitled “The ‘Great Goddess’ of Teotihuacan: Fiction or Reality?” was published in Ancient Mesoamerica by Zoltán Paulinyi. According to the author, by giving the title Great Goddess to this figure, scholars agreed that she was the principal omnipotent deity of Teotihuacan. Paulinyi goes on to argue, however, that this interpretation is questionable as it is based on combined pieces of iconography that have little or nothing to do with each other. Through this combination of information, Paulinyi asserts, the Great Goddess idea took hold among scholars. Finally, Paulinyi suggests that the Great Goddess never existed, and points out that instead of an all-embracing deity, the images may be understood as representing a number of separate gods and goddesses.

Mural of the Spider Woman or Great Goddess in the Tepantitla palace, Teotihuacan. (Escocia1 / CC SA-BY 3.0 )

Another article, “A New Attribution of the Gender Attribution of the ‘Great Goddess’ of Teotihuacan” was published in 2015 by Elisa C. Mandell, also in Ancient Mesopotamia . Mandell’s article deals with another aspect of the figure, i.e. its gender. The titles Spider Woman and Great Goddess both reflect the commonly held assumption that the figure is a female. Mandell, however, questions this supposition, and argues that the Spider Woman is in fact a figure of mixed gender. In addition to the figure’s iconography, Mandell also looks at instances of mixed gender across cultures and time periods in Mesoamerica, specifically the Maya, the Nahua, and during the colonial and modern periods.

The two recent articles show that there are still many uncertainties surrounding the figure of the Spider Woman. By looking at the figure from different angles, some are hoping to cast doubt on and challenge commonly accepted interpretations, as well as offer alternative ways of understanding this mysterious character. It is unlikely that any interpretation will put the mystery to rest once and for all any time soon. In addition, unlike the Storm God, who has an equivalent in the Aztec Tlaloc, the Spider Woman seems to have been unique to Teotihuacan and she was not adopted by later Mesoamerican cultures. As a consequence there is not much that we know for certain about the Spider Woman, and that the things we do know about her are largely based on the speculation of scholars.

Top image: Photo of a mural at the Tetitla compound, 500 yards (500 meters) west of the Avenue of The Dead, showing the Spider Woman or Great Goddess of Teotihuacan. Images on the sides coming from her hands/arms symbolize abundance and prosperity. (Public domain / CC BY 2.0 )

By: Wu Mingren

References

Bone, L., 1986. Teotihuacan Mural Project. [Online]

Available at: https://cool.culturalheritage.org/waac/wn/wn08/wn08-3/wn08-301.html

Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, 2001. Teotihuacan: Mural Painting. [Online]

Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/teot4/hd_teot4.htm

Faith, A. G., 2020. The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan. [Online]

Available at: https://historicalmx.org/items/show/77

Heyworth, R., 2014. Tetitla: Jaguar Lords, Owl Warriors & the Great Goddess. [Online]

Available at: https://uncoveredhistory.com/mexico/teotihuacan/tetitla/

History.com Editors, 2018. Teotihuacan. [Online]

Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-americas/teotihuacan

Mandell, E. C., 2015. A New Analysis of the Gender Attribution of the “Great Goddess” of Teotihuacan. Ancient Mesoamerica, Volume 26, pp. 29-49.

Monsieur Mictlan, 2020. Mural of the Great Goddess. [Online]

Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/great-goddess-mural-tetitla-teotihuacan

Paulinyi, Z., 2006. The “Great Goddess” of Teotihuacan: Fiction or Reality?. Ancient Mesoamerica, 17(1), pp. 1-15.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020. Teotihuacán. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Teotihuacan

UNESCO, 2020. Pre-Hispanic City of Teotihuacan. [Online]

Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/414/

www.crystalinks.com, 2020. Teotihuacan Spider Woman. [Online]

Available at: https://www.crystalinks.com/mayanspiderwomen.html

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 12th, 2020

October 12th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: