This week cannot pass without a word on Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh and husband of Queen Elizabeth II who died last Friday. He was close in age to my late grandmother Tamam. In 1948, UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, estimated she was born in 1922, one year after Philip. Lacking the privileges he had to grow to 99, she died in 2006.

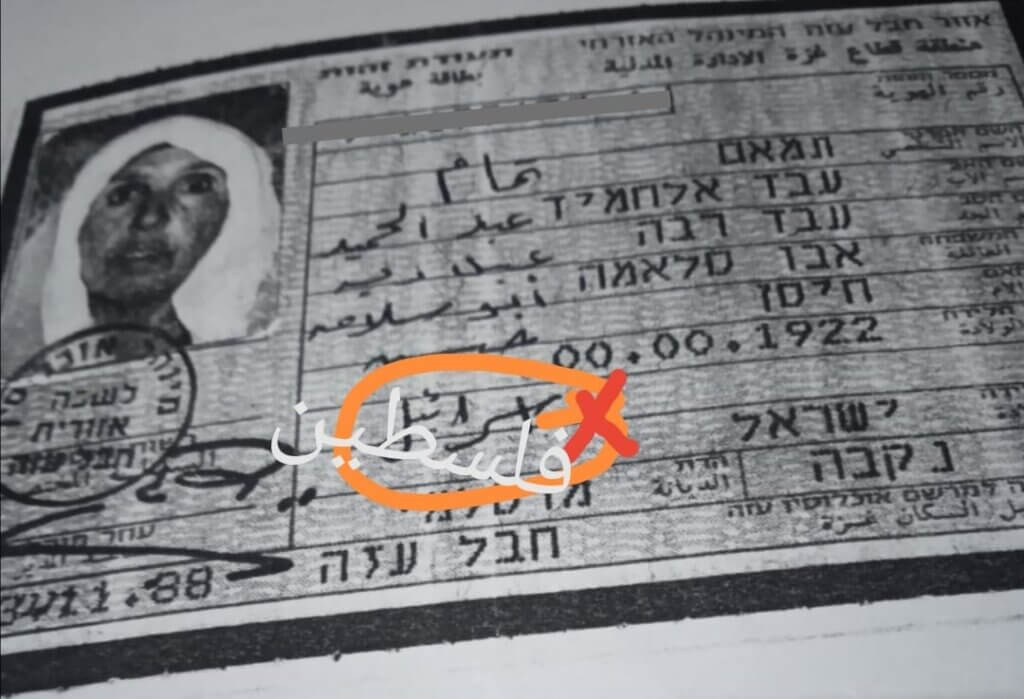

Note down that Tamam and Philip were more than a quarter-century older than Israel. But a simple fact like this is distorted in documents. Her Palestinian ID card issued by Israel–and for that matter issued to everyone from the “Nakba generation,” those whose lives were upended by the events of 1948–identified her birthplace as Israel. Power and lots of entitlement combined together failed to acknowledge the geography of the time, “Palestine.”

In the words of the poet Mahmoud Darwish, “Lady Earth, mother of all beginnings and endings/She was called Palestine/and she is still called Palestine.”

For history’s record, I circled the word “Israel” and replaced it with “Palestine.”

Yet this essay is not just about the politics of naming but also how characters like Philip, and settler-colonial enterprises like Israel, continue to be celebrated. A petition calling for his commemorative statue in London is nearing 10,000 signatories, while my grandmother was more worthy of such a celebration of life. British news is currently celebrating the “extraordinary” life of His Royal Highness, participating in a procession that overwrote Philip and his family’s complicity in the Israeli dehumanization of the Palestinians.

She may not have been a royal or as privileged as Philip, but she lived a happy, simple life in the village of Beit Jerja north of Gaza, on land she loved and nurtured, and the land nurtured her back.

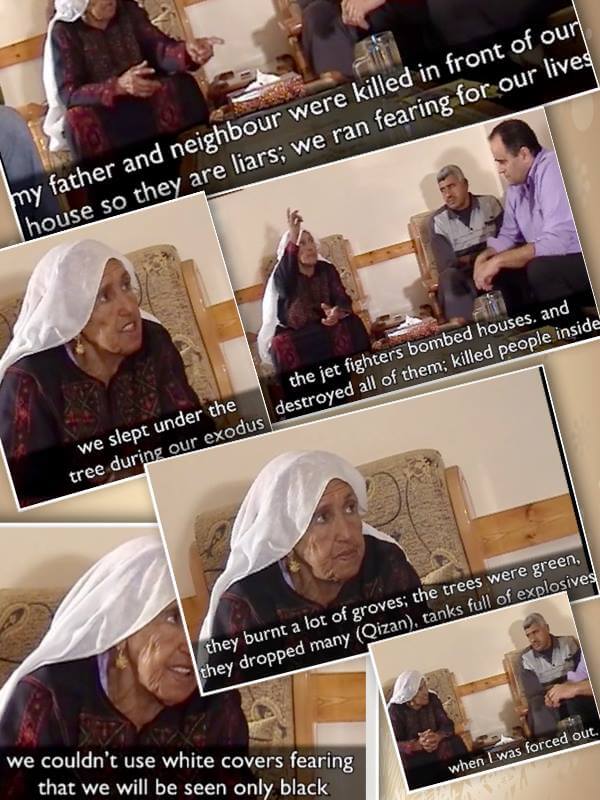

In 1948, Beit Jerja became one of 418 Palestinian villages and towns that were completely depopulated and destroyed. After the war, many ruins were covered with green spaces and parks in an act of memoricide, to conceal reminders of an earlier Palestinian presence. My grandmother lost everything in the Nakba, one of 750,000 Palestinians who became refugees. With her family she sought refuge in Gaza, which they thought was temporary, planning to return to their original village in a matter of weeks. She held onto this dream and never gave it up. It was her song of life. However, two generations later I was born in that same camp. Jabalia refugee camp is the largest camp in the occupied Palestinian territory.

When she died in Jabalia almost two decades ago, it was just a few kilometers from Beit Jerja, where she wanted to be buried.

Conversely, Philip’s lifetime oversaw the last generation of Britain’s imperial empire. Born the son of Greek and Danish royal families, and a direct descendant of Queen Victoria, his familiar ties stretched across Europe and are linked back through the age of colonial conquest. His uncle, Lord Mountbatten, was appointed the last Viceroy of India, a position he held until Indian Independence, which incidentally was the same year he married Queen Elizabeth II, and the last full year my grandmother lived in Beit Jerja.

While British imperialists saw themselves as purveyors of modernism and “improvement” flowing from England to the empire, in fact, their strategic interest was greed: control over the colonized people’s wealth, resources, and human capital in the form of the brutal trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Palestine became a British Mandate in 1920, two years before my grandmother was born. Many saw British rule as a betrayal of the right and promise to independence made during World War I. This was further entrenched the day British troops and administrators departed from Palestine, and Israel declared itself a state. By 1949, at the close of the war, Israel controlled 78% of historic Palestine, my grandmother was a refugee and Philip was a lieutenant on a British ship stationed in Malta, then a British colony.

From this time on, Britain has had a persistent bias in favor of Israel and a disregard of Palestinian rights and lives, even while the royal family themselves boycotted traveling to the region for decades, regarded as a snub over the occupation. This changed as the empire fell and England became a prominent supporter of Israel, politically, economically, and militarily.

The ties from British colonial control to today must not be brushed under the carpet, especially since Palestinians are stuck in uninterrupted cycles of violence, living under a complex system of part apartheid, part settler-colonialism, and part military occupation.

Philip in fact holds the honor of breaking the monarchy’s public rebuff of Israel by becoming the first royal to visit Israel and East Jerusalem. His mother, Princess Alice of Battenberg, with whom he was estranged for most of his life, notably sheltered Jewish refugees at her home in Athens during World War II. Philip was living in England at the time, serving in the British Royal Navy. Upon her death in 1969, she was entombed in England, but her remains were later transferred to the Mount of Olives in East Jerusalem in 1988. The arrangement was brokered with Israel and the Greek and Russian churches, even though the site is located in occupied Palestinian territory.

In 1994 Philip became the first British royal to visit Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory since the Mandate ended, attending a ceremony for his mother at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Jerusalem, and visiting her grave. Since then, other royals have also visited.

The ground’s holiness has been stolen by their imperial violence. If Philip wanted to join his mom on Mount of Olives, his privileges would allow him. But my grandmother was not afforded the same, by virtue of her being Palestinian. Burials in my homeland should not be a luxury afforded to a foreign monarchy when the indigenous population is prevented from even visiting their original lands. Their connection was based on a fantasy that spans generations, Princess Alice has an aunt buried close by, while my grandmother’s connection was obvious, yet denied.

When my grandmother passed away, it was deeply shocking. She was fit and alert until her very late years, with sharp memory. Until the last week of her life, she never missed a daily visit to the birdcage for pigeons we had on the rooftop of our home in a five-story building. She died at a time when Gaza was facing an unprecedented scale of violence. She died suddenly and peacefully but she was exhausted. A few days earlier, she decided to stay at my uncle’s house as it sounded safer to her than our home – Israeli tanks were advancing nearby.

During her stay at my uncle’s in 2006, Israeli forces invaded Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun a little more than a mile to the north and arbitrarily shelled civilian houses, killing 19 and wounding 40. My grandmother could not cope and she died of a sudden heart attack. My family and I believe she died of fear.

Not long before she passed, when I was 14, I participated in training for documentary film making. Once, I was assigned to take the camera and film a day at home. She saw me holding a medium-size video camera and the stand as I climbed to the rooftop of our building. When she asked what I was about to do, I said, “just going to record the sunset for my documentary course.” No matter what excuses I gave, she was decisive: “No sunset and no filming. The soldier in the sky does not differentiate between a child setting up a video camera and someone launching a rocket.”

Several other memories I have of her indicate that she was severely injured. She was overly cautious in unexpected ways. She buried scissors, knives, and any kind of sharp household tools in the garden whenever she heard a military invasion was nearby. She experienced so much pain at the hands of Israeli forces that made her believe they’re capable of anything inhumane.

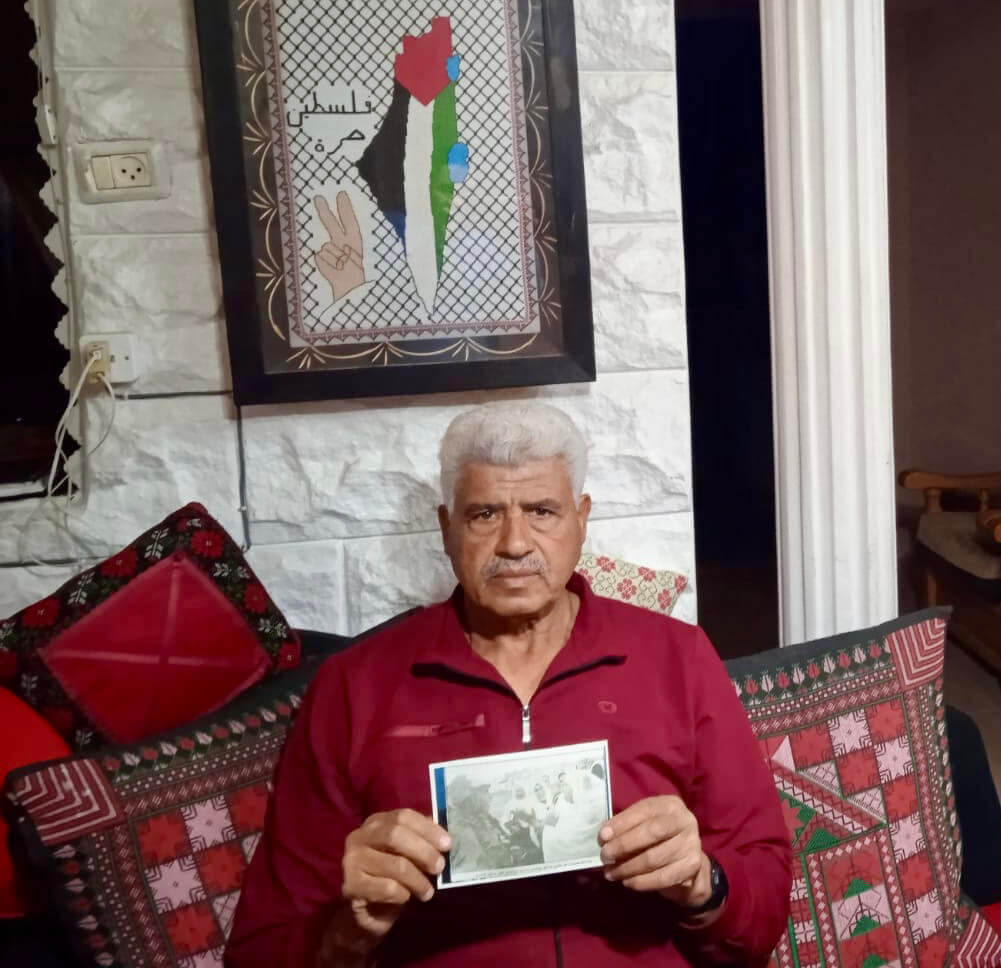

Despite her hardships, my grandmother’s life was truly extraordinary, a life of struggle for dignity. She was a mother of eight children. She was our chief protector when there were night raids to our home; the last happened a month after my birth when my father was kidnapped by a huge military force who broke into the house in the middle of the night, turned everything upside down, and confiscated his notebooks and family albums. At one point, four of her sons were simultaneously held in Israeli prisons, dispersed between Gaza, and Nafha Prison in the Negev desert. The longest-serving was my father who was incarcerated for a combined total of 16 years (1972-1985, 1988, 1989, and 1991). This experience consumed her middle-age years, which were dedicated to maintaining the wellbeing of her children in spite of various forms of imprisonment.

She never missed a rally for Palestinian political prisoners. As she continued to care for her other children and my grandfather who had a physical disability, she managed to find time to hold placards of her detained sons at the Red Cross office in Gaza. Like many ordinary Palestinians, she never received public recognition of her sacrifices and labor of love. She never submitted to oppression, instilling in her children and grandchildren the courage of speaking truth to power.

I fear speaking about her experience as a mother of political detainees and forgo giving her due justice, but she often summed it up in this way: “I do not wish it on my worst enemy.”

My grandmother was deeply loved and respected, especially by my father who often said he owes her his strength and survival, both inside and outside prison. The more I grew up, the more I understand her and my father’s unique relationship. She was selfless; she devoted her life to her family; she had a protective instinct as a mother that physically bore on her. More than once she sandwiched herself between soldiers and her sons, resulting in her receiving punches.

I remember her as a heroine who stood against injustice whenever it happened. A picture of her was once featured in a local newspaper during the first Intifada. She was fearless and furiously shouted at an Israeli soldier who was armed to the teeth, at a checkpoint on her street. What the photo doesn’t show is that the military barrier prevented her from accessing her house, where my grandfather was sick and alone during a curfew which often happened and led to military checkpoints suddenly proclaimed at random places at the convenience of Israeli soldiers.

My father hid a clipping of the photograph against my grandmother’s wishes, as she feared it could be used against her and her family, and continued to demand its destruction throughout the second Intifada when Israeli violence further intensified. Such actions, being unafraid and defiant at a checkpoint or any picture that testified to Palestinian resistance, were often a pretext for arrests. So while photographs can be a tool of resistance and dignity for the occupied, my grandmother mostly wanted to destroy it.

The image, however, captures a priceless moment when the military might is weaker than a righteous woman. She was larger than the sun in my eyes. She co-raised my siblings and me. While I do not want to participate in romanticizing Palestinian resistance, a natural reaction to oppression, my grandmother held a lifelong thirst for safety even inside her house, a thirst that only return to her original home in Beit Jerja would have treated.

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 16th, 2021

April 16th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: