Throughout history, needing the help of a surgeon was almost a death sentence because if one did not die on the operating table, one would feel the excruciating agony brought from the heavy crude chop of the surgical blade. Because of this continuous trauma, humanity has searched the world to find the most effective numbing elixirs.

The search for the perfect numbing agent was pursued for thousands of years. Some of the earliest records reveal ailments and elixirs from Sumer, ancient Babylon, Assyria, Dynastic Egypt, India, and China. However, the ancient secrets for anesthesia were not as effective as modern methods today. The journey of how the west now uses anesthesia is just as interesting as how it works.

It is surprising how many of today’s illegal drugs were once essential in ancient medical practices. Drugs such as marijuana, opium, cocaine, and even very potent alcohol were still used well into the early 20th century before the advancement of western medical practices. What is even more surprising is that opium, infamously known as one of the most addictive drugs in the world, was the first drug worshipped for its medical purposes.

Opium And The Earliest Anesthesia

Opium is by far one of the oldest forms of anesthesia used by humanity, and its use continued well into the 20th century for medicinal purposes. The earliest record of anesthetic use derives from Ancient Sumer , sometime in 3400 BC. The words “Hul Gil” appear in the cuneiform text, which translates to “the plant of happiness,” or more commonly, the Opium poppy.

Opium was associated with the Sumerian goddess Nidada, goddess of grain and crops in the Mesopotamian world. Opium appeared to be refined for use into a nectar paste called “Arat Pa Pa” in later Assyrian texts.

The medicinal properties of opium have been known for thousands of years ( Xiao / Adobe Stock)

Although it was worshipped for its beneficial properties, it was often associated with a painless death. Opium paste was mixed with poison hemlock throughout the ancient world, creating a drowsy and painless effect for those about to die. To the ancients it presented itself as the best alternative to enduring a painful death.

Alternatives Were Available

The popularity of opium spread widely across the ancient world to both the East and the West. In the West, however, opium took on a more negative connotation. The Ancient Greeks associated opium with the gods Hypnos, god of sleep, Nyx, the god of night, and Thanatos, the god of death.

In ancient Egypt, although opium was used, according to the Ebers medical papyrus, Egyptians used mandrake fruit to create their anesthesia. Though different to the opium plant, rendering the active substance from the root was almost identical, and both plants had very similar effects. This also revealed that there were other alternatives that were not as severe as opium.

Other ancient civilizations, especially in eastern India and China, cultivated and used cannabis and aconitum, also called “Wolf’s Bane.” Ancient China used potent forms of wine as a liquid additive to accompany those plants.

As written in the ‘ Hua Tuo ‘ (145 AD- 220 AD) and then in the later book of the Han (430 AD), the most popular anesthesia was a very strong concoction of wine and herbs known as Mafeisan (meaning ‘boiled numbing hemp powder’). This remedy was unfortunately lost to time due to Hua Tuo burning his own material.

Hua Tuo (Gan Bozong / CC BY 4.0 )

This elixir rendered a patient unconscious. Although surgeries were forbidden in Ancient China due to Confucian beliefs, Chinese herbal medicine included effective forms of anesthesia which provided great results.

In the Middle East, between 940 AD – 1040 AD, a medical wine similar to Chinese Mafeisan was prepared by Zoroastrian priests. This elixir was used for individuals before operation. Another method that was used with a ‘soporific sponge.’ A sponge soaked with sweet-smelling toxins was placed over the nose and mouth of a patient.

This method of mixing wine with herbal cannabis appeared very popular in the Middle East and Ancient China. Because of trade, it was no surprise that this method would also be popular in Europe as well.

Similarly to the Middle East, between 1200 AD – 1500 AD Medieval England also used medicine called ‘dwale’, a wine mixed with opium, lettuce, bryony, henbane, hemlock, and vinegar, and bile. In Medieval England, they also prescribed a sedative infused to a sponge made from unripe mulberry, flax leaves, ivy, mandragora leaves, lettuce seeds, lapathum, and hemlock with hyoscyamus. It seemed that civilizations worldwide already understood the concepts of controlled amounts of sedatives to make individuals remain unconscious during surgery.

The historical progression of various forms of anesthesia through medicinal paste, then to medicinal wine, slowly made its next step to a gas form. However, it would only be in the 18th century when medical practitioners would experiment with actual gas chemicals and more refined medicines.

Anesthetic Gas

Throughout the 18th century, scientist and clergyman Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) and Thomas Beddoes (1760 – 1808) pioneered mixing gases and observing their effects on patients. In 1775, Priestley published six volumes of his findings in “experiments and observations on different kinds of air.”

Thomas Beddoes (Charles Turner Warren / Public Domain )

With these findings, Beddoes founded the Pneumatic Institution for Inhalation Gas Therapy in 1798. Shortly after hiring James Watt (1736 – 1819) and Humphry Davy (1778 – 1829), the institution blossomed as one of the leading places to manufacture isolated gases.

Additionally, the institution gained further notoriety once Davy discovered the effectiveness of nitrous oxide as medical anesthesia. His experiments revealed that subjects would break into laughter while feeling little to no pain during surgery. Due to this side effect, Davy keyed the term ‘laughing gas’ or ‘happy gas.’

Davy’s presentations became riotous parties named “ether frolics” where audiences were delightfully encouraged to partake and inhale nitrous oxide for its mood-altering side effects and entertainment. By the end of 1830, Davy’s work was prominent in academia and medical publications throughout the Northeast United States .

One of these eager participants was called Dr. Horace Wells. However, his contribution to nitrous oxide was far grimmer.

Dr. Wells and Samuel Colt (creator of the Colt 45 pistol) tried to profit from the pain-numbing abilities of nitrous oxide. However their efforts were severely damaged after a humiliating demonstration at Harvard Medical school, in which a patient was not fully anesthetized by the gas and screamed in agony during the removal of his molar.

Dr. Wells lost his reputation and committed suicide three years later, and the use of nitrous oxide was then abandoned for 150 years. But Dr. Wells would ultimately be venerated when he would be re-labeled the “discoverer of anesthesia.”

Queen Victoria with Prince Albert and their nine children. Prince Leopold is circled (Caldesi and Montecchi / Public Domain )

Another popular gas anesthetic during the 1840s was chloroform, pioneered first by Dr. John Snow. He used chloroform on Queen Victoria while she was in labor with Prince Leopold, her eighth child. This sedative carried no side effect of laughing and quickly became more reliable throughout Europe.

By the 20th century, chloroform had replaced nitrous oxide. However, chloroform soon fell out of favor with some medical communities when further use revealed that an overabundance of it would cause cardiac arrest and cardiac toxicity.

Following in the footsteps of the successes of Priestley, Davy, Beddos, and Watt, and learning from the mistakes of Horace and Colt, other medical doctors continued experimenting with gases. One of these which proved promising was diethyl ether which took center stage on October 16, 1846.

Dr. William T.G Morton and Dr. John Collins Warren gave a demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital to which they successfully used diethyl ether on a patient during surgery. The patient, Gilbert Abbott, had a tumor under his jaw. He was put under with ether and successfully operated on. Their administration of ether proved paramount, and it became one of the leading methods of anesthetics.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, diethyl ether, nitrous oxide, and chloroform appeared to rise and fall out of favor with regions of the western world. The deployment method for either chloroform or nitrous oxide was simplicity itself: a patient would wear a mask over their mouth with a fabric in between the mask covering and the patient. The fabric would be doused with either nitrous oxide or chloroform, and the resultant evaporate would be breathed in.

The Return To Opioids

While the use of mixed gases was taking hold in the 19th century, another kind of pain killer existed in the form of opioids. Similar to ancient times, opium soon returned as a popular form of anesthesia, particularly after the pharmacist Friedreich Wilhelm Serturner (1783-1841) successfully isolated a crystalline compound that was particularly potent. He named his discovery morphine, after the Greek god Morpheus.

The new compound appeared to be a concentrated dose of opium, that would provide extremely effective pain relief and euphoria. This drug was mass-produced during the 1850s and was administered through a hypodermic needle.

Morphine was easily administered and effective, but also highly addictive (Aurelija Diliute / Adobe Stock )

In the Americas, morphine became known as the wonder drug that could cure everything from alcoholism to tremors, asthma, menstrual cramps, and gastrointestinal diseases. Morphine was widely desired, and further processing of opium became possible, leading to the development of Oxycontin, opium pills, and several other forms of opioids. Opioids were so popular that in 1888, Boston mentioned that 15% of all prescriptions were made up of some form of opioid.

Although the pain relief aided those who suffered either from the traumas and wounds from the American Civil War or helped women with menstrual cramps or anxiousness, the ultimate side effect from morphine and these opioids were often intense addiction and unfortunate overdose.

During the 1800s, over 60% of women made up the largest victims of opioid addiction. By 1895, it was reported that roughly 1 in every 200 Americans were addicted to some form of opioid. But this was just the start.

The Bright New Hope of Cocaine

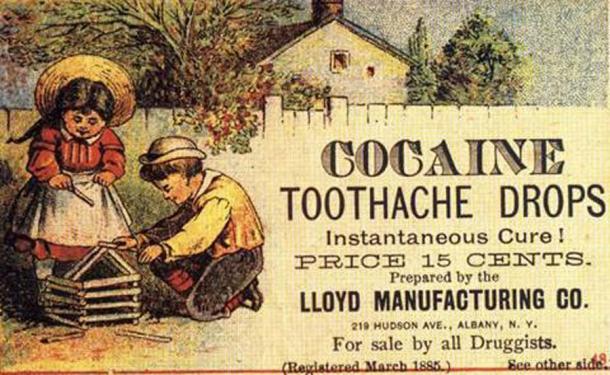

Along with opioids and morphine, an alternative painkiller was introduced known as cocaine. This drug was first isolated from coca leaves by German chemist Albert Nieman in 1859. Cocaine became an alternative anesthetic when patients showed allergic reactions to ether or chloroform. Cocaine was excellent as a numbing agent, that was particularly effective with surgery in the mouth.

Cocaine was also used as a topical ointment that helped with body pains and muscle aches. Cocaine became so popular that many companies used cocaine in their products and as a stimulant drug to fight depression, sexual dysfunction, and drowsiness. However, similar to the problems brought from morphine, a great addiction epidemic was taking hold, and both opioids and cocaine had to be regulated.

She don’t lie… cocaine was also an effective painkiller, but had its own problems (KiloByte / Public Domain )

The epidemic addiction to these various drugs became so rampant that by 1900, many doctors were encouraged to lessen their prescriptions and find alternative uses that were not based on opioids. However, the heavy restriction and regulation of medical opium and cocaine in the United States would only happen in 1909.

Anesthesia Today

With the development of these successful anesthetics, surgeries could be performed more slowly and more precisely. A patient could be rendered completely unconscious and immobile, allowing for a surgeon to carry out more complicated procedures, especially when it came to sensitive areas such as the brain, chest, and abdomen.

Although ether, chloroform, nitrous oxide, cocaine, and opioids had dominated as the main forms of anesthesia for a lot of human history, all of them carried immense and detrimental side effects that often led to massive discomfort, substance abuse, addiction, and death. However, without these previously existing forms of painkillers, no advancements would have occurred.

Later on, the implementation of newer technologies would aid in the invention of safer assisting technologies like mask regulators and digital monitors.

In the current era, although the opioid epidemic is far from over, it is very rare for people to die from anesthesia. Frequently, most complications are caused by negligence in its implementation rather than the drugs themselves. On average, it is 1 out of every 300,000 people who succumb to death. Though these numbers may still seem high, compared to the statistics in the 19th century, these numbers are immensely better.

Currently, there are many newer and safer anesthetic alternatives to ether, chloroform, and nitrous oxide. The most popular options are the brand names Sevolflourine and Isoflurane. Additionally, further advances in mask regulators and monitoring equipment have become common practice limiting the possibility of accidental death or irritation.

Modern anesthetics are considered extremely safe and effective (ISAF Headquarters Public Affairs Office / CC BY 2.0 )

The pursuit of the perfect anesthetic continues. But, as history shows, perhaps in the next 50 years, even Sevoflurane and Isoflurane will be banned and regulated for something better yet to come. It only makes one wonder what legal medicinal substances of today will be made illegal and dangerous in the future?

Top Image: Anesthetics allowed for far more detailed, careful surgeries to succeed. Source: Marina / Adobe Stock.

By B. B. Wagner

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 30th, 2021

September 30th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: