On January 15, Mathilde Krim, a scientist and socialite, died on Long Island at 91, and the obituaries described her courageous leadership in the fight against AIDS. Krim was incensed by the widespread stigmatization of AIDS victims as somehow deserving the disease, and she worked to lift prejudice that kept our society from taking the illness seriously. (I saw her work for myself, attending a fundraiser at her East Side townhouse back in the 90’s).

What the news has not told you about is Krim’s other great achievement: helping to swing the White House to Israel’s side in the 1960’s. The no-daylight policy of U.S. alignment with the Israeli government, so obvious today in Trump’s deference to Netanyahu, was born under Mathilde Krim’s dear friend Lyndon Johnson. In the feverish weeks surrounding the 1967 war, Krim, who had once emigrated to Israel, and her husband Arthur, a leading fundraiser, were continually at Johnson’s side, and advised him on what to say publicly.

“Johnson was the pivotal president for our relationship with Israel and I think Mathilde Krim’s sway over Johnson was such that it turned the entire relationship, allowing Israel to continue on, especially after the Six Day War, in a manner that defied not only the U.N. but the whole world with regard to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians,” says Martin Brod, a retired systems analyst in New York who has long studied the role of Israel’s American friends in cementing the special relationship. Here is that story.

Mathilde Krim was a person of depth, intrigue and compassion. Born Mathilde Galland in 1926 in Italy to parents of Swiss, Italian and Austrian background, she moved with her family to Switzerland as a girl and went on to be a brilliant student, earning a Ph. D. in genetics from the University of Geneva.

When she learned about the Holocaust as a teenager, Krim identified with Jews. She felt as she did for AIDS victims 40 years on, a need to protect them against bigotry, abandonment, and rejection from the wider community.

These feelings led Krim to support Zionist militants during and after the war. The New York Times obituary by Robert D. McFadden includes one reference to her Zionist zeal:

Appalled by newsreels of Nazi concentration camps in 1945, she sought out Jewish activists, joined the Zionist underground Irgun and spent a summer smuggling guns over the French border for resistance fighters against British rule in Palestine.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in 1948, she married an Irgun comrade, David Danon, a Bulgarian medical student, and converted to Judaism.

Danon had been exiled by the British from Palestine for his Irgun activities, and Krim saw him as a “dashing and heroic figure” dedicated to a noble cause that had used terrorism to achieve its ends, she said in an interview with the late Donald Neff, a former Time Magazine correspondent, for his book Warriors for Jerusalem: The Six Days that Changed the Middle East (1984).

Krim said she was moved by the “despair” of the Zionists. The blowing up of the King David Hotel in 1946 and the assassination of Lord Moyne in 1944 “represented the depth of the convictions of Danon and the Irgunists, the measure of both their commitment and their despair,” Neff related. Danon spent his time “recruiting and carrying out secret Irgun operations throughout Western Europe,” and his wife used her bicycle to transport explosives across international borders bound for the Irgun in Palestine– “a seemingly innocent petite and pretty blonde out for a bicycle ride,” Neff says.

Mathilde Krim in the lab, undated photo

She and Danon had a daughter and moved to Israel in 1953, but there the marriage ended, and Krim didn’t stay an Israeli that long either. She was working as a geneticist at the Weizmann Institute south of Tel Aviv when board member Arthur Krim came to visit. Arthur was a leading entertainment lawyer and studio executive, a former chairman of United Artists and Orion Pictures, and assiduously political. He was an adviser to several Democratic presidents due to his fundraising network, backing traditional Jewish causes: Israel and the U.S. civil rights movement.

“The story was that the head of the Weizmann Institute introduced Mathilde to Arthur Krim, suggesting that he might find her interesting because she spoke many languages and was a very attractive woman,” Brod says. “It developed into a romance after she showed him around the institute.”

Arthur and Mathilde Krim with President Kennedy, May 1962, at the Krim residence in NY. Photo by Cecil Stoughton.

The two married in 1958, when Mathilde was 32 and Arthur was 48. Mathilde soon moved to New York, and went to work at Sloan Kettering as a researcher. And Arthur became chair of the Democratic National Finance Committee.

Marilyn Monroe singing Happy Birthday, Mr. President in Madison Square Garden in 1962.

It was on that account that Mathilde formed one of the most important relationships of her life. In May 1962 Arthur Krim helped assemble Hollywood names for the famous fundraising gala at the Madison Square Garden at which Marilyn Monroe sang Happy Birthday, Mr. President to Jack Kennedy (a few months before her death). The after-party was held at the Krim mansion, Mathilde Krim related later in an interview with the LBJ Library; and Vice President Lyndon Johnson was an outsider at the party. Mathilde empathized with Johnson and befriended him as he sat on a staircase.

I think he was a great man, that’s the best word. And he was imposing. He was not only physically an imposing man, and great. He had a great heart, he had a great intelligence, and he put them both to work, in fantastic ways.

Brod believes that Mathilde Krim was strategic in forming the friendship.

From the day they first met which was at the party for JFK at the Krim residence in the city– from that day forward she speaks proudly of having nurtured a relationship with Johnson because Johnson was not part of the JFK inner circle. I don’t think it was an accident that she approached Johnson and developed this ongoing relationship. I have a feeling that from her entry into the United States if not before there was a plan of how she could best serve Israel and she began serving them when she was living in Switzerland in her first marriage and her work with the Stern gang. She had a strong stomach to involve herself with that kind of terror, and she certainly lived up to it here.

The transition from Kennedy to Johnson in 1963 was an important moment in the history of the special relationship.

Kennedy had bridled at the pro-Israel influence. In 1960, his campaign was in trouble when a group of Jewish leaders gave him $500,000 at the Pierre Hotel in New York, and then “interrogated Kennedy stringently on matters affecting Jews and Israel,” (as Abba Eban later related). “As an American citizen [Kennedy] was outraged” by the effort to take “control” of JFK’s Middle East policy, his friend the newspaperman Charles Bartlett told Seymour Hersh.

As president, Kennedy maintained some distance from the Israeli government. He supported the right of return of Palestinian refugees and vigorously opposed Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. The CIA had obtained evidence of the Israeli nuclear project in the desert at Dimona– claimed to be a fabric factory, Brod says– and in the year before he was assassinated, Kennedy had pushed Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and his successor, Levi Eshkol, to account for the activities.

His successor had fewer scruples about backing Israel. Johnson’s political career was interwoven with Jews, as his wife later reflected, and he saw that nuclear nonproliferation “made for bad politics,” as Hersh says in The Samson Option, because it alienated the Jewish community. Johnson ultimately suppressed intelligence reports that Israel was becoming a nuclear power. “By 1968, the President had no intention of doing anything to stop the Israeli bomb,” Hersh writes.

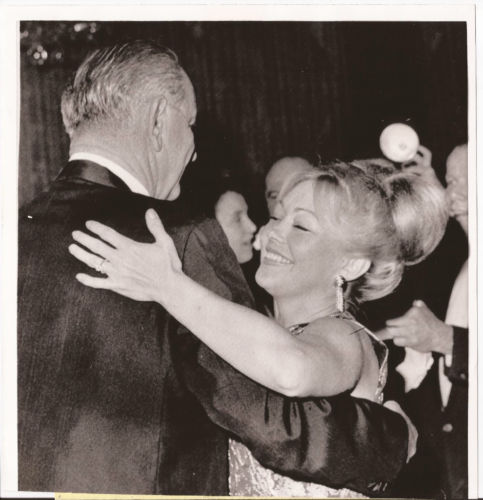

Mathilde Krim dances with Johnson at January 20, 1965, inaugural ball following his reelection in 1964.

Mathilde Krim was undoubtedly a factor in that policymaking. Throughout his presidency, the Krims were among Johnson’s very closest friends. They had a room in the White House and built a house on Lake Lyndon B. Johnson in the Texas hill country so as to be near his ranch in Stonewall when he was on vacation there. Johnson stayed at their house in New York.

It has been suggested that Mathilde Krim was LBJ’s lover. “It was a barely hidden secret in leading government circles in Israel and the United States at the time that Mrs. Krim was extremely close to Lyndon Johnson,” Helena Cobban wrote in her blogpost on Krim last week. While Brod points out that Johnson was a “competitive womanizer,” according to his aide Bill Moyers, and certainly the president had social opportunities alone with Mathilde Krim.

Mathilde Krim and Lady Bird Johnson with President Johnson in a helicopter en route to the LBJ Ranch from the Krim Ranch, November 1966. Photo by Mike Geissinger of the White House.

But the essence of the relationship was political; and the Krims’ influence was apparent throughout the days leading up to the 1967 war, when Johnson signaled to Israel that it had a yellow light to go ahead with the war, a signal “tantamount to a green one,” in the view of scholar William Quandt, as it let the Israelis know that the U.S. would not condemn them for launching the war, and if they got into trouble the US would come to their side.

Mathilde Krim was a “key channel” for the Israelis to signal their plans to Johnson and to get signals in return, Cobban writes:

The huge role that Mrs. Krim played in 1967 is well-known to everyone who has seriously studied US-Israeli relations at that time. After all, she was an integral part of a well-oiled pro-Israeli influence movement at the heart of the US political system, and the DC-Tel Aviv signaling process that she was part of worked strongly in Israel’s favor to transform not just the Middle East but the whole shape of global politics.

Donald Neff also says that Mathilde Krim’s influence swayed American policy: Johnson “left himself more open to a passionately partisan voice than was prudent or even healthy during the accelerating crisis.”

Neff’s book documents Mathilde Krim’s steady presence at Johnson’s side that spring. Ten days before the war began, Johnson spent Memorial Day weekend 1967 at his ranch in Texas with the Krims, and regularly received communications about the mounting crisis in the Middle East from Eshkol with the Krims close at hand.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, Arthur Krim, A.W. Moursund, Lady Bird Johnson, Mathilde Krim. At a ranch near Kingsland, Texas, April 13, 1968. White House photo by Mike Geissinger.

“We talked with him all the time about Israel,” Krim told Neff. Johnson admired the Israelis because he was a rancher dealing with dry land, she said, and “he had an entirely emotional liking for Jews, for what they had suffered, for the way they had been discriminated against, as he felt he had been discriminated against by the Eastern Establishment.”

On June 3, the following Saturday night, the Krims were Johnson’s company at a fundraiser at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, intended in part to shore up his support in the Jewish community. Arthur Krim hosted the fundraiser; and Johnson sat between Mathilde Krim and Mary Lasker, another huge contributor to the party (and widow of Albert Lasker, an Israel backer). The legendary fundraiser Abe Feinberg was there, and served as a conduit for the Israeli war plans, reports William Quandt in his book Peace Process.

“[H]e leaned over and whispered in his ear: ‘Mr President, it can’t be held any longer. It’s going to be within the next twenty-four hours.”

Two days later, on the morning of June 5, Mathilde Krim was in her bed in her room on the third floor of the White House when Johnson came in to tell her the war had begun– though she noted to Neff that the president was accompanied by “a couple of aides.”

Later that afternoon, the Jewish community was angered when State Department spokesperson Robert J. McCloskey said at a press conference: “Our position is neutral in thought, word and deed.” The statement suggested that the U.S. would do to Israel what it had done under Eisenhower in 1956, and force the country to withdraw from lands it seized in war.

Over the next few days Johnson came under intense pressure to deny McCloskey’s assertion. “Seldom, if ever, had a president been subjected or allowed himself to be subjected, to such a concerted campaign as Lyndon Johnson that Wednesday. It was all pro-Israel; Arabs seemed to have no advocates,” Neff notes acidly.

Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas phoned Johnson, and Mathilde Krim dictated memos to the president, urging him to repair the damage that McCloskey had done with Jewish Americans.

In one memo that LBJ later read to Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Krim called on the president to make a speech calling “for a permanent peace settlement.” Those words meant that the U.S. would not demand an Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories.

In another memo, Krim told the president he did not understand “the resentment still lingering [among Jews] after the McCloskey statement” and the political dangers inherent. She channeled the Israelis and American Jews:

“There are reports of very strong anti-American feelings in Israel—that Israelis feel they have won the war not with the U.S. but despite the U.S. In the Jewish community it is very difficult to explain the coincidence of the statement and the beginning of hostilities. The Jews are a people with a persecution complex and they understood the statement of the State Dept. to mean that in an hour of gravest danger to them… that this country disengaged itself… That is why they reacted so violently…

“There is great danger that the Jewish rally to be held tomorrow in Lafayette Square here will be anti-Johnson, rather than a pro-Israel demonstration. Even Minister [Ephraim] Evron [at the Israeli embassy] says things are going out of hand.”

She advised Johnson that he could “salvage” the situation if he made a “very strong statement.” Krim then went back to New York City, but her last call to the White House June 7 was at a minute before midnight, Neff reports.

She was back at Johnson’s side on the weekend, which he spent at Camp David preparing a speech that he would give on Monday, June 12, “which was to establish the nation’s official policy in the Middle East,” Neff says. Johnson read drafts of his speech Saturday night at dinner with the Krims and others, “inserting additions and making changes, also accepting comments and suggestions from all at the table,” according to notes in the Presidential Daily Diary.

Johnson gave the speech on Monday morning, and issued five principles of peace in the region, beginning with “security for all nations in the region.” And though the list included “justice for the refugees,” Johnson did not call on Israel to withdraw– not till all principles were attained.

Feinberg called the White House to say that the Jewish community was delighted with the speech. “He hit the nail right on the head.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson and other guests watch after-dinner entertainment as 10,000 antiwar demonstrators are outside in the streets. Mathilde and Arthur Krim are seated on the President’s right. Century Plaza Hotel, LA, June 23, 1967. Photo by Yoichi Okamoto.

Two weeks later Mathilde and Arthur Krim were at Johnson’s side in Los Angeles as he held a fundraiser at the Century Plaza Hotel. Outside the hotel, 10,000 demonstrators demanded an end to the Vietnam War, and police turned on them with batons. The newspapers put the melee on the front page.

Of course it was Johnson’s support for that war, and the protests against it, that caused him in the end to leave the presidency. Mathilde Krim later asserted that she and her husband encouraged Johnson to try and deescalate the Vietnam War. When Johnson wanted to commit 200,000 more troops to Vietnam, Arthur Krim convinced him not to, and so did she. “‘Please don’t do it.’ ‘Really?’ ‘No you shouldn’t do it’,” she relates the conversation between Arthur Krim and LBJ.

I don’t know to what extent it was Arthur’s influence and a little mine– I was chiming in.

Days after the 67 War, in Los Angeles. June 23, 1967. L-R: Lynda Bird Johnson, Arthur Krim, Mathilde Krim, Lew Wasserman, President Lyndon B. Johnson, Mrs. Wasserman. Century Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles, California, photo by Yoichi Okamoto, LBJ Presidential Library.

The Krims were later at Johnson’s side in March 1968 as he got ready to announce that he was leaving the White House.

“He had nobody around but us and [Johnson’s wife] Lady Bird and [daughter] Lynda,” Mathilde Krim said of that occasion. “He was really a lonely man.”

The loneliness can be glimpsed at a New Year’s party on Dec. 31, 1968, at their ranch when he was a lame duck.

New Year’s party, 1969, Arthur Krim’s “Santana” Ranch, Kingsland, Texas. Lady Bird Johnson, LBJ, Mathilde Krim, Daphna Danon Krim, and Arthur Krim, left to right. Photo by Jack Kightlinger

Over the years critics of the Israel lobby have dug up photos of Johnson and Mathilde Krim in intimate moments to hint at the unseemly nature of Zionist influence over American presidents.

Lyndon Johnson and Mathilde Krim, two weeks after the 1967 War, at a fundraising dinner at the Century Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles, California. As Johnson spoke at the fundraiser, 10,000 demonstrated against the Vietnam War outside the hotel and police responded with violence.

White House Photo by Yoichi Okamoto.

Meantime, the mainstream press ignores the relationship. That is the most important part of this story: Mathilde Krim did not want to be known as the influencer she was, and the press has cooperated in burying the tale.

In this video in which she discusses her relationship to the president to the Johnson Library, Krim says:

“I didn’t talk to him about military or political issues even. With my husband, yes, he did talk about these things. But I overheard many conversations.”

Martin Brod says this is a lie. “She was in the weeds on this. The idea of calling Johnson– when every minute of his life had to do with what was going on in the Middle East and other affairs– for her to dictate a memo or pick up the phone and believe she didn’t have to apologize for writing and calling, tells us a lot about their relationship.”

Brod is moved by Krim’s contribution to AIDS research.

Martin Brod, who has studied Mathilde Krim’s life

“If it was only that she’s an angel,” he says. “And apparently she only wants to be known as that. She wasn’t looking for recognition in Israel, because she would have a 50 foot high statue because of what she was able to do, mainly with LBJ. But then she says she never did talk about anything political with him. And even in Wikipedia very little is mentioned of her other activities. Why? Because the so called mass media have their own unpublished rules about what gets attention.”

They are missing a fascinating story about the ability of a charismatic intelligent zealot to gain the audience of the most powerful man in the world as history was unfolding.

“One of the things that made Israel’s miracle come true was Israel’s ability to use people like Abe Fortas and Arthur Goldberg,” Brod says. “They had a huge Rolodex of influential people, whether mass media or fundraisers, that they could contact and effectively use depending on the situation, and there was no one more needed during the Six Day War than Mathilde Krim.”

When Abba Eban told a disapproving Johnson in Texas that Israel could no longer hold off its attack, it was Johnson and Mathilde who flew back to the White House, leaving Lady Bird behind at the ranch. It was Johnson who awakened Krim in her White House bedroom to tell her the news of the war beginning. It was Mathilde Krim who who even as she was forced to get back to work in New York left Johnson a pro-Israel speech to quiet a pending Jewish demonstration.

As for Johnson’s willingness to turn a blind eye to the Israeli nuclear program, or its attack on the USS Liberty on June 8, 1967, we can only guess at Mathilde Krim’s advice to him. As she later advised others, anyone can have an influence over policy– you just have to throw yourself into it.

“Lyndon Johnson was so willing to be Mathilde Krim’s hero that he would do almost anything he could get away with,” Brod concludes. “And that was quite a lot.”

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2018/01/secret-life-mathilde/

Related posts:

Views: 5

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 27th, 2018

January 27th, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: