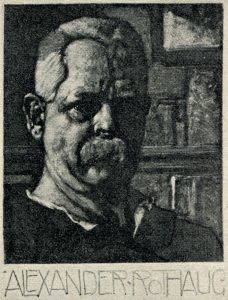

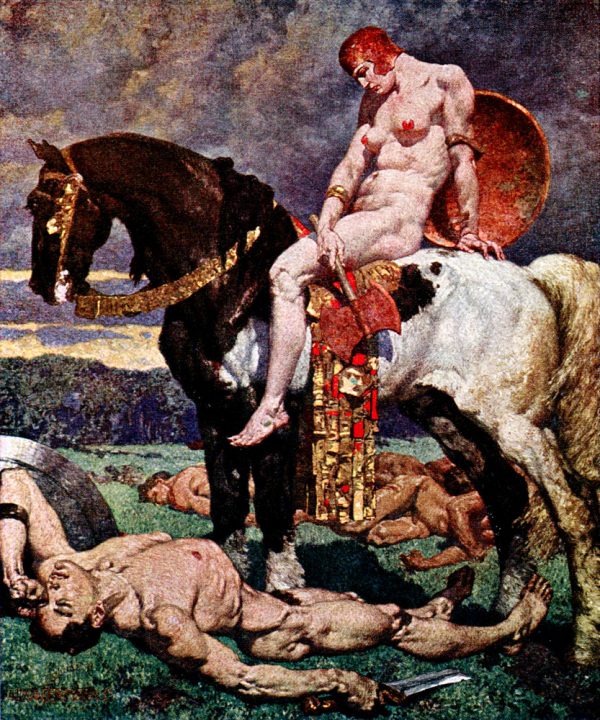

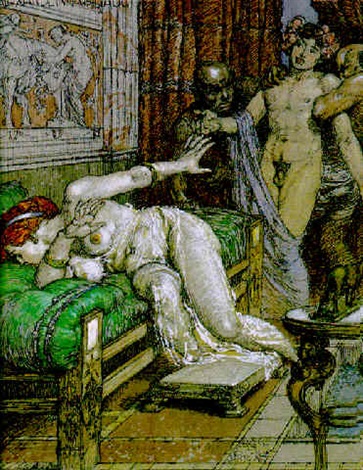

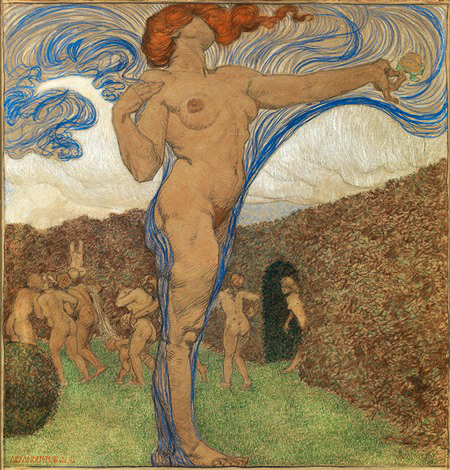

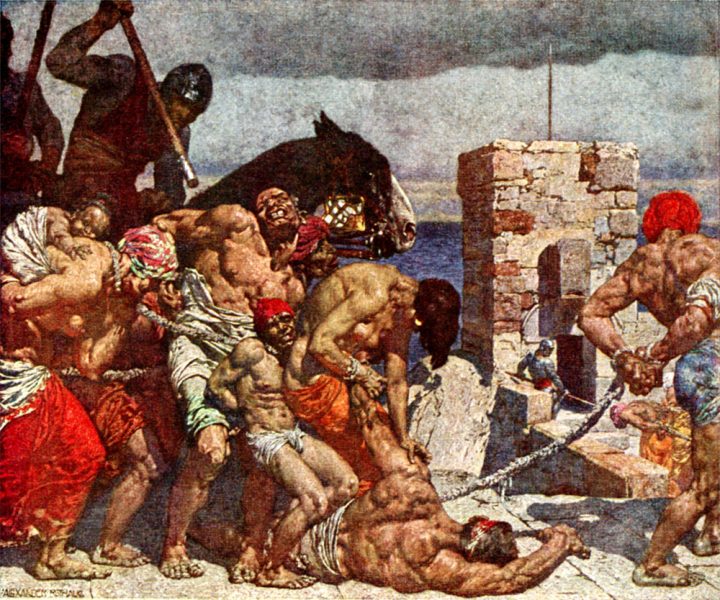

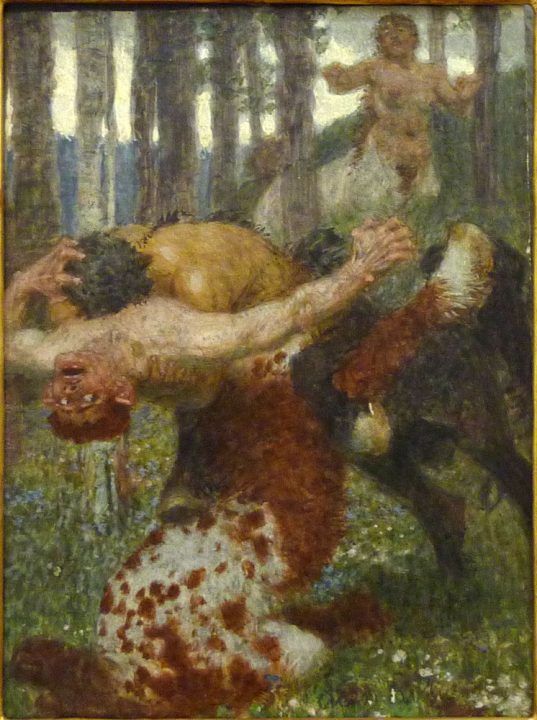

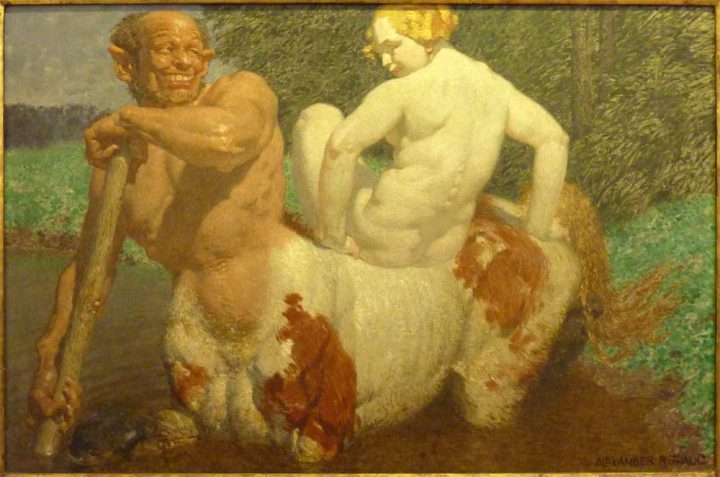

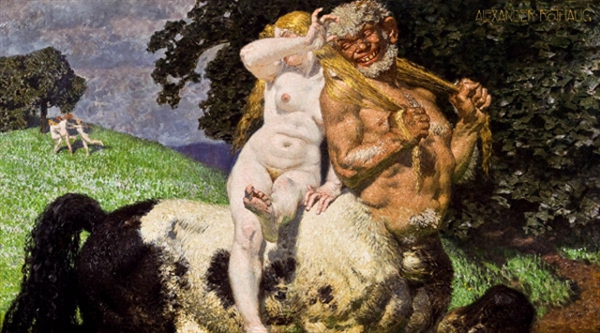

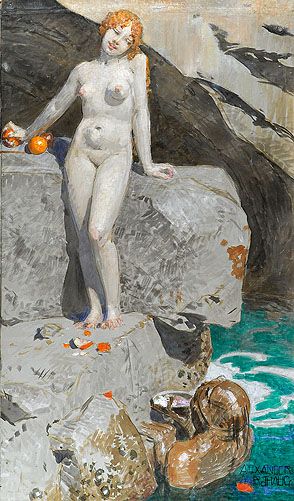

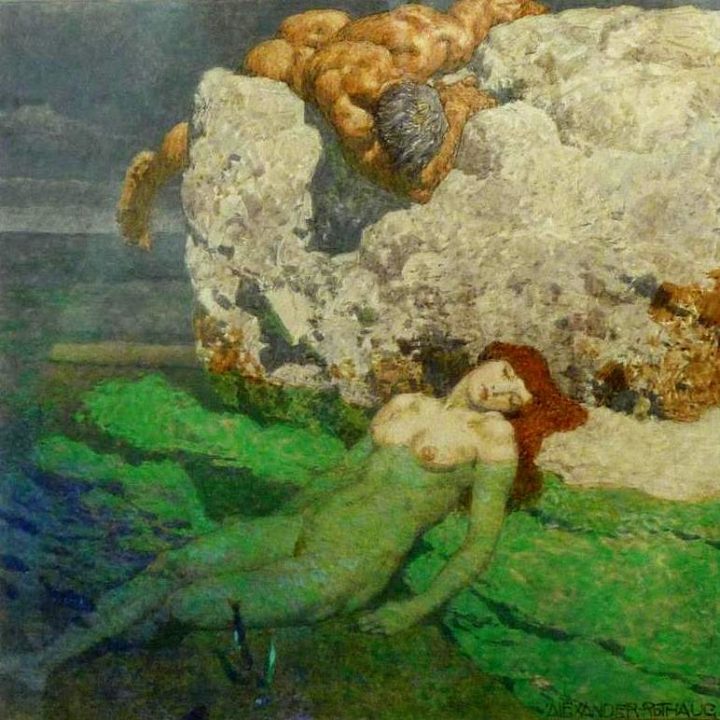

Alexander Rothaug, in spite of having been quite popular back in his heyday, is one of those artists one only gets to know by doing some research. I suppose this must be due to the fact that these kinds of painters are remembered today only by connoisseurs as in this ‘post-modern age’ true art has been (for the most part) relegated to certain ‘academicist’ corner, regardless of its high visual value. Whatever the case Rothaug’s paintings echoed those of his then contemporary Franz Von Stuck to a large extent, both in style and imagery but also, in my personal opinion, they served as a prelude to what future American artists of the fantastic such as Frank Frazetta and Richard Corben were going to create in subsequent decades. To support this statement I would only mention paintings such as Simsons Rache (Samson’s Revenge) (1928), Die Entführung (The Abduction) and Die Auslieferung (The Delivery). Doubtlessly the latter two would be considered totally ‘racist’ by the emasculated liberal standards of this dying age. It is also worth remarking that Rothaug’s popularity didn’t dwindle even when his life was close to an end, as the Third Reich still exhibited many of his works in very distinguished galleries in his native Austria.

Biography

Alexander Rothaug was born on March 13, 1870 in Vienna (then still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) and died March 5, 1946. He became a painter and illustrator of renown. Rothaug, like many great men of the German folk, had to grow up in narrow and restricted circumstances by means of his own will and his own strength. He was the son of Theodor Rothaug and Karoline Rothaug (born Vogel). His maternal ancestors were also painters and sculptors. With the two-year-old brother Leopold Rothaug, Alexander received the first painting lessons from his father Theodor.

In 1884, he began learning sculpture with Johann Schindler (1822-1893) at the Viennese Academy of Arts. In 1885 he studied painting with August Eisenmenger, Christian Griepenkerl and Franz Rumpler. The painter Leopold Carl Müller also had an important influence on him as a teacher.

In 1892 Rothaug moved to Munich, where he worked as an illustrator for the humorous magazine Fliegende Blätter (The Flying Leaves), thanks to this work he became known all over the world. Rothaug’s paintings were regularly shown at exhibitions in The Munich’s Glass Palace (from 1899), in Hamburg and at the Great Art Exhibitions in Berlin. In the Viennese artist’s house, he was represented for the first time at the Jubilee Exhibition in 1898, and from 1909 onward regularly at Künstlerhaus exhibitions. In 1896 he married Ottilie Lauterkorn. He undertook study trips to Dalmatia, Italy and Rügen. In May 1910 he became a member of the Cooperative of Fine Artists of Vienna. In 1911, an extensive article on Alexander Rothaug appears in the journal Kunst-Revue. In 1912 he took part of the invitation by Archduke Ludwig Salvator in Majorca, Spain. Rothaug created the publication Skizzen aus Miramar on his stay there. These many trips inspired Rothaug on his landscape motifs. In 1913 Alexander Rothaug received the Baron Richard Drasche Award for outstanding artistic achievements.

In addition to the monumental paintings for theater buildings, Rothaug, together with secessionist Rudolf Jettmar, created ceiling paintings in the Kurhaus of Meran in 1914. In the inter-war period he also created wall paintings for sacred buildings in Lower Austria and Vienna as well as templates for ceramic building sculptures in the Hauptschule Aspern (1937, Vienna 21, Oberdorfstrasse 2). For the Grand Hotel de l’Europe in Bad Gastein, he created a wall-mounted painting cycle on Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen.

In 1933, under the title Statics and Dynamics of the Human Body, Rothaug published a systematization of the human body through theory of proportion in the form of a loose leaf collection of 10 sheets. He also wrote a 38-page treatise entitled Knowledge in Painting with the three-page appendix Thoughts on Art and the Artist.

Nearing the end of his life by 1941 (during Third Reich Germany) Alexander Rothaug was present with 38 works in a collective exhibition by the Künstlerhaus in the building of the Secession, together with works by Maximilian Lenz, Johann Viktor Krämer, Klimt and Schiele.

Alexander Rothaug’s grave dedicated to him is located in Grinzinger Friedhof (group 15, row 1, number 2) in Vienna.

Style

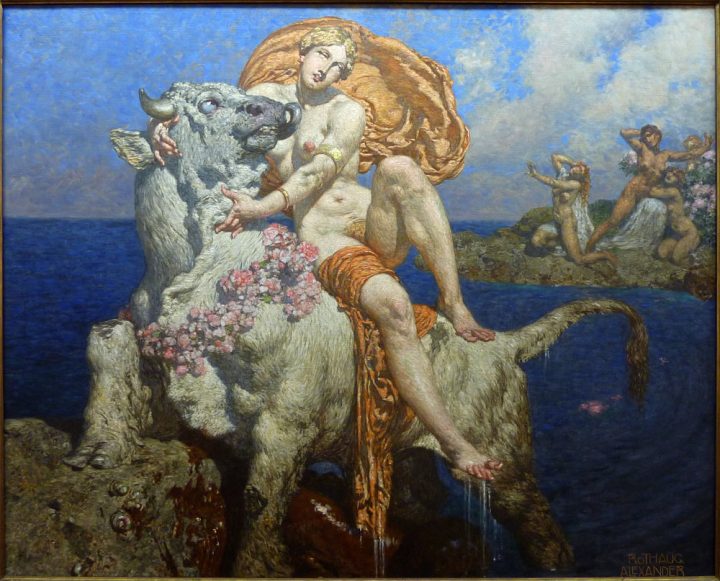

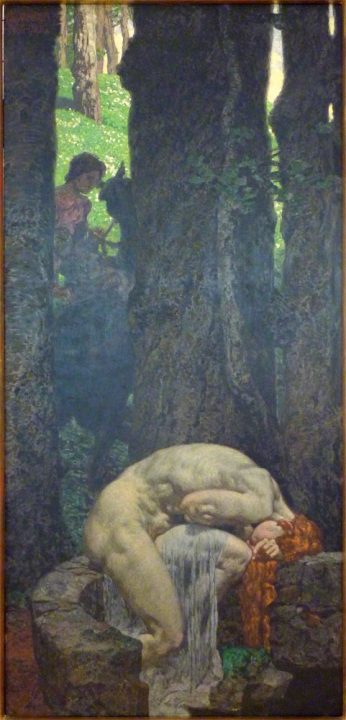

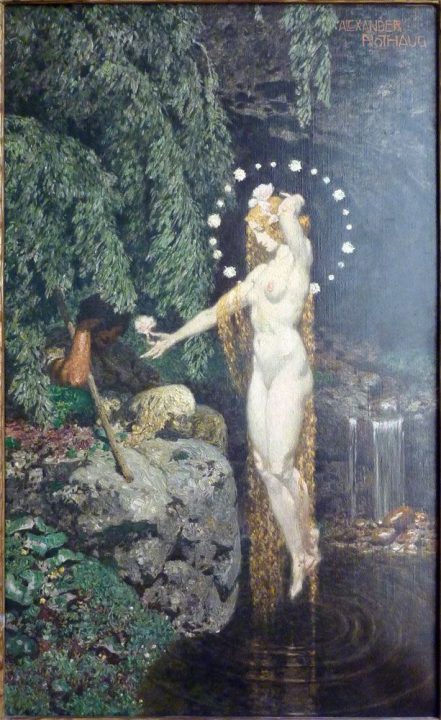

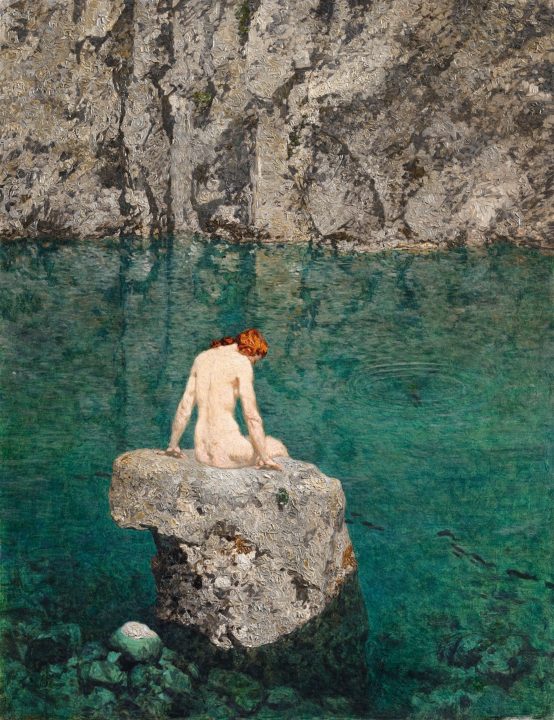

Rothaug is one of those artists who found an individual style at an early age, to which he remained true until the end with technical refinement as well as thorough knowledge of his themes. He chose his pictorial motifs from ancient mythology and the German saga, with powerful dramatic scenes as well as elegiac-melancholic representations with full artistic passion. Strong pathos in the expression, coupled with a masterly portrayal of the human figure in its varied dramatic movement, were typical of Rothaug’s large-format paintings which showed rich light and color effects. Romantic natural representations also dominated his work. Rothaug also left an extensive graphic work including book illustrations, such as Quo Vadis, The Last Days of Pompeii and The Golden Ass. As a commercial graphic artist, Rothaug also designed stamps.

Prof. Gunter Martin described Alexander Rothaug as follows:

The close kinship with the late Southern German painter-prince, Franz von Stuck, is obvious. Rothaug had the painstaking brush stroke for plump women and masculine musculature, with motifs from classical mythology turned into scenes of barbarian savagery.”

In the first volume of the 12th year (1934/35) of the German monthly The True Eckart, Arthur Roessler honored the artist in his lifetime, under the heading A German Art Master – A Little Address to the Painter Alexander Rothaug:

In his figurative compositions, too, there are many artifacts of antiquity, an antiquity seen through the eyes of the Renaissance, which seems to be completely transformed inside German minds like Alexander Rothaug’s. The artist emerges from the inherited ancient longing for a golden age of art which, as Dürer complained, “was lost and hidden for a thousand years”. Rothaug owes this longing to this “antique style”. His images and the strong pathos in the expression and beauty of the human being is represented by him with the mastering of form and an infinite variety of movements.”

Rothaug possessed the ability to gather from the natural world qualities which most people have long stopped seeing or feeling. The visual appearance of Rothaug’s art is not only sensual, but also poetic. The narrative in his paintings, however, must not be overlooked by the artistically inclined. At the end of the day Alexander Rothaug was a strong German romantic.

Anyone who had access to Master Rothaug’s workshop was certainly astonished at the seemingly endless number of conscientiously accurate studies in color and form, with dozens of sketchbooks, complete staple folders, and some other staggering works; studies which convincingly showed the thorough knowledge of the master when he created his great compositions, apparently drawn purely from the imagination or inspired by poetry and legend. Rothaug agrees with those masters of art, who were deeply impressed by the conviction that the visual arts are really nothing else than the study of nature. A study which made the antiquity and the Gothic so great and sublime. Of course, it could only be made great and sublime, because it was not only done with the senses and the mind, but with heart and soul.

Main Sources

– Alexander Rothaug Aus Wien Geschichte Wiki

– Alexander Rothaug Ober St.Veit An der Wien article

– Alexander Rothaug [www.dorotheum.com]

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/mythological-art-alexander-rothaug/

Related posts:

Views: 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 28th, 2017

April 28th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: