Mt. Olympus, the Peloponnesian War, Pericles, Athens, and, of course, the Parthenon. When one considers ancient Greece, these are only a few of the topics that usually spring to mind. The heroic age of gods and men, the historical wars between Greek city-states, powerful strategoi and their prominent cities and, of course, architectural feats beyond compare. What does not spring to mind, however, are the mysterious megalithic structures the Greeks call drakospita, or “dragon houses.”

Megalithic Architecture of the Dragon Houses

Likely dating to the Preclassical period of ancient Greece, the dragon houses of Euboea are among the mysteries of the past which have yet to be fully understood. They first gained international attention when British geologist John Hawkins took note of the strange structures while ascending Mount Ochi (also written as Oche) on October 21, 1797. Although many archaeologists have been drawn to the dragon houses over the years, they have yet to explain them.

Resembling the stepped pyramid of Djoser in Pre-Dynastic Egypt and the temple complexes of Pre-Columbian Teotihuacan, these megalithic houses are structures built without mortar. Small, thin, mostly flat stones make up the buildings, stacked atop one another, kept in place with the use of jambs and lintels. Large megaliths are used in various places throughout the dragon houses, usually toward the roofs, positioned in a fashion that is similar to what is seen at Stonehenge.

A megalithic drakospita in Greece. ( siete_vidas1 /Adobe Stock)

While little is understood of these dragon houses, the number of the structures is far more than expected. Around twenty-three of these houses exist on the island of Euboea—most between Mounts Ochi and Styra—each building made of megaliths. In fact, scholars are constantly boggled by the sheer size and weight of the single megalith resting on two equally large post stones, together forming a doorway. How this megalith could have been lifted and placed atop the posts is as much a mystery as the reason behind the building of these structures.

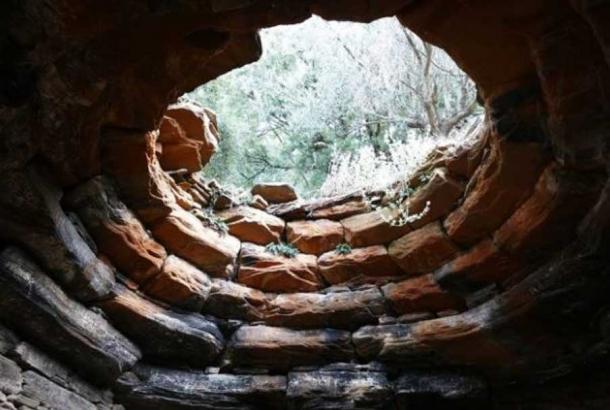

It should further be noted that, not only is the reason behind the dragon houses a consistent question among scholars, but their location is equally astonishing. These dragon houses are situated at very high altitudes, making the weight and size of the megaliths even more shocking. The builders had to find a way to transport such large stones from a much lower altitude, and then construct the houses at a height at which it was likely unpleasant to work. Furthermore, each structure possesses a Pantheon-like opening in the roof, likely intended for natural sun or moonlight to illuminate the interior of the buildings.

Drakospita have holes in their roofs. ( CC BY 3.0 )

Why Were the Greek Dragon Houses Built?

Another curious aspect about these megalithic buildings is that there is no known reference to them in ancient writings. Archaeologists have had to rely on local oral legends and folklore, as well as some descriptions of the sites by explorers, as the jumping off point to try to explain the structures.

Archaeological excavations have been conducted as well, but they have provided few answers to the mysteries of the dragon houses. So far, the most notable artifacts that have turned up during digs are fragments of ceramics and inscriptions dating from the Preclassical Period to the Hellenistic Period – including one potsherd with text in an unknown script. Other finds include some utensils and animal bones.

Ochi Dragon-house: Roof. (Klaus-Norbert/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

Researchers from the Department of Astrophysics at the University of Athens also studied the dragon houses on Mount Ochi from 2002 to 2004. They wanted to see if the structures were aligned with any astronomical features and concluded that there is a relationship between the sites and the Sirius star system as it appeared around 1100 BC. This led the researchers to suggest that the dragon houses were ancient astronomical observatories.

Other theories have arisen saying that the so-called dragon houses might have actually been shrines to Hera, Zeus, or Herakles. Theories regarding the rituals that might have taken place within, however, are few.

Another popular belief is that these megalithic buildings were either stations at which guards were positioned during the Hellenistic period, or they were warehouses in which supplies may have been stored. This has some support in the discovery of the ceramics. If these locations had been stations, they likely would have served as a base and been equipped with food, supplies, and soldiers, ready for whatever battle might be on the horizon. As warehouses, the list of necessities would have likely been non-perishable food items; yet the premise would have remained the same: in case of emergency, break megalith.

Dragon house, Evbia, Greece. ( siete_vidas1 /Adobe Stock)

What’s in a Name?

Another question lies in the structures name: why are these buildings called drakospita? The first thing one must understand is that the ancient Greek conception of dragons is not the same as the current one. Drako, interpreted as “dragon” in the present, really describes a mythical creature more akin to modern perceptions of giants. In light of this description, one can more easily understand why these big mountain houses have been named drakospita by archaeologists.

Until more is understood about how these buildings were made and/or by whom they were constructed, referring to them as abodes of the supernatural is a surprisingly fitting description. After all, who else would have had the strength to lift and move megaliths across the ancient world?

Inside a Palli-Lakka dragon-House building near Styra, Euboia, Greece. (Klaus-Norbert/ CC BY 3.0 )

A Significant Site for Megaliths

Though the uses of these megaliths are unknown, their location is likely of great importance. For now, Euboea is the only known island in the Aegean upon which these houses stand. Moreover, Mt. Ochi, where one of the best-preserved dragon houses remains, is the tallest point of south Euboea.

Perhaps there is a correlation between the proximity of the megalithic buildings to both air and sea, as Mt. Ochi is near the prominent bay city Karystos. Might these structures have some relationship to an ancient and more elemental religion than the Classical Greek traditions recorded by Hesiod and Homer? While this theory uses only one of over twenty known sites as an example, perhaps readers will use this as a stepping stone to investigate possible explanations for the purposes of the ambiguous drakospita.

Top Image: Dragon house in Greece. Source: dinosmichail /Adobe Stock

Updated on October 7, 2020.

References

Carpenter, Jean and Dan Boyd. 1977. “Dragon-Houses: Euboia, Attika, Karia.” American Journal of Archaeology. 81.2. pp. 179-215.

Chidiroglou, M. 2010. “The Archaeological Research in the Region of the Modern Municipality of Styra: Old and New Finds.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 10.3. pp. 19-28.

“The Mysterious Dragonhouses of Evia.” Visit Greece . Accessed September 28, 2017. http://www.visitgreece.gr/en/culture/monuments/the_mysterious_dragonhouses_of_evia

Liritzis, I, G.S. Polymeris, N. Zacharias. 2010. “Surface Luminescence Dating Of ‘Dragon Houses’ And Armena Gate At Styra (Euboea, Greece).” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. 10.3. pp. 65-81.

Reber, Karl. 2010. “The Dragon Houses of Styra: Topography, Architecture and function.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 10.3. pp 53 -61. Accessed September 29, 2017.

Theodossiou, E. and V.N. Manimanis. 2009. “Study and Orientation of the Mt. Oche ‘Dragon House’ in Euboea, Greece.” Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage . 12.2. pp. 153-158.

Wilson, Nigel. 2013. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece . Routledge. pgs. 276 and 278.

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 8th, 2020

October 8th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: