I am contemplating a bit of a literary mystery — a 1924 book, You Gentiles, by Maurice Samuel.

Struck by its bold and unusual title, I sought out the book and read it, and increasingly tried to understand the intention of the writer.

There is no mention of Palestine or Zionism in the book. But it is a Zionist polemic, meant to leave only separation, territory for Jews, as the solution to hostility from gentiles in the diaspora.

Samuel was a leader of the Zionist Organization of America, and a protege and lifelong friend of Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, the future first President of the State of Israel.

For antisemites, who have quoted and republished the book a number of times in the last century, it is a revelation of how Jews “really feel” about gentiles, as proof of the “real” nature and intention of Jews.

The publisher of a 1985 reprint sold on Amazon.com blurbs it with,

A Jew looks at the difference in the world outlook and mental differences between the Jew and the non-Jew. He shows how the Jews view the world by a different set of values. Why the Jew is getting the upper hand on the non-Jew of today.

“A nice account that would be labeled anti-semitic if anyone but a jew [sic] wrote it. Highly recommended,” a buyer-reviewer says.

“You Gentiles” was republished in 1999 by a white nationalist publisher. Before that, something called Christian Nationalist Crusade republished it in 1958, and another publisher paired it in a volume with writings of automotive pioneer Henry (“The International Jew”) Ford, with the title “Communism is Jewish!”

Indeed, “You Gentiles” reads as a Jew-hating fever dream.

Samuel writes,

If anything, you must learn (and are learning) to dislike and fear the modern and “assimilated” Jew more than you did the old Jew, for he is more dangerous to you.

…We try to adapt your institutions to our needs, because while we live we must have expression; and trying to rebuild them for our needs, we unbuild them for yours.

This is a vision of Jews as somewhere between a nationality and a separate species.

Despite my familiarity with Zionist texts, this book struck me. I had under-valued Zionism as an effort for Jewish “national” fulfillment as much as refuge.

I read the book searching for clues that it was satire or an exercise in obviously preposterous assertions, freely typecasting gentiles and valorizing Jews.

This was my failure to comprehend. I had understood, but not deeply, the consequence of the Zionist anthem’s words, To be a free nation in our land, The land of Zion and Jerusalem.

This was also a failure of my imagination. Samuel writes so well and lucidly, a cultured man, that I didn’t see how he could be voluntarily boxing himself into ethno-nationalism. He calls himself an atheist, so his choice is presumably not a felt religious imperative.

Samuel later wrote that he happily grew up in Manchester identifying with England and its heroes and history, until at a certain point he did not feel it was his England in the same way as for his school fellows. Throwing himself into Jewish culture and Zionism solved his perceived problem, and forced his conclusion that Jews best not live among others.

In the first chapter is his thesis,

Wherever the Jew is found he is a problem, a source of unhappiness to himself and to those around him. Ever since he has been scattered in your midst he has had to maintain a continuous struggle for the conservation of his identity.

The cause of this unhappy situation is that

…in this Western world there are essentially two peoples as spiritual forces, only two human sections with essential meaning — Jew and gentile.

Samuel argues “You Gentiles” that because Jews developed with a demanding daily schedule of ritual devotions, they have a worldview and “life-will” that is oriented toward direct devotion to a “national” God.

That difference in temperament makes them unsuited, and destructive even, the more they are integrated into more-trivial gentile society, and despite adaptations to their surrounding societies.

Just as Theodore Herzl’s foundational Zionist text “Der Judenstaat” (“The Jewish State,” 1896), Samuel’s book insists on the impossibility of Jews and non-Jews living in stability and respect, and the necessity of Jews living in their own land.

“You Gentiles” is a functional extension of “Der Judenstaat”, but attributes intrinsic characteristics to Jews and gentiles, in a way not flattering to gentiles.

I became aware of Maurice Samuel’s book when seeing it mentioned in “Palestine Diary“ by Frederick H. Kisch, published 1939, an account of his time as a Palestine Zionist Executive chairman based in Jerusalem, 1923-31.

Kisch mentions seeing Samuel multiple times in New York City and Palestine.

Kisch wrote that in New York in 1925, the Zionist Organization of America was “helped by some fiery spirits such as Rabbi Stephen Wise and the young Jewish author Maurice Samuel whose book You Gentiles was being widely read and discussed at the time of my visit.”

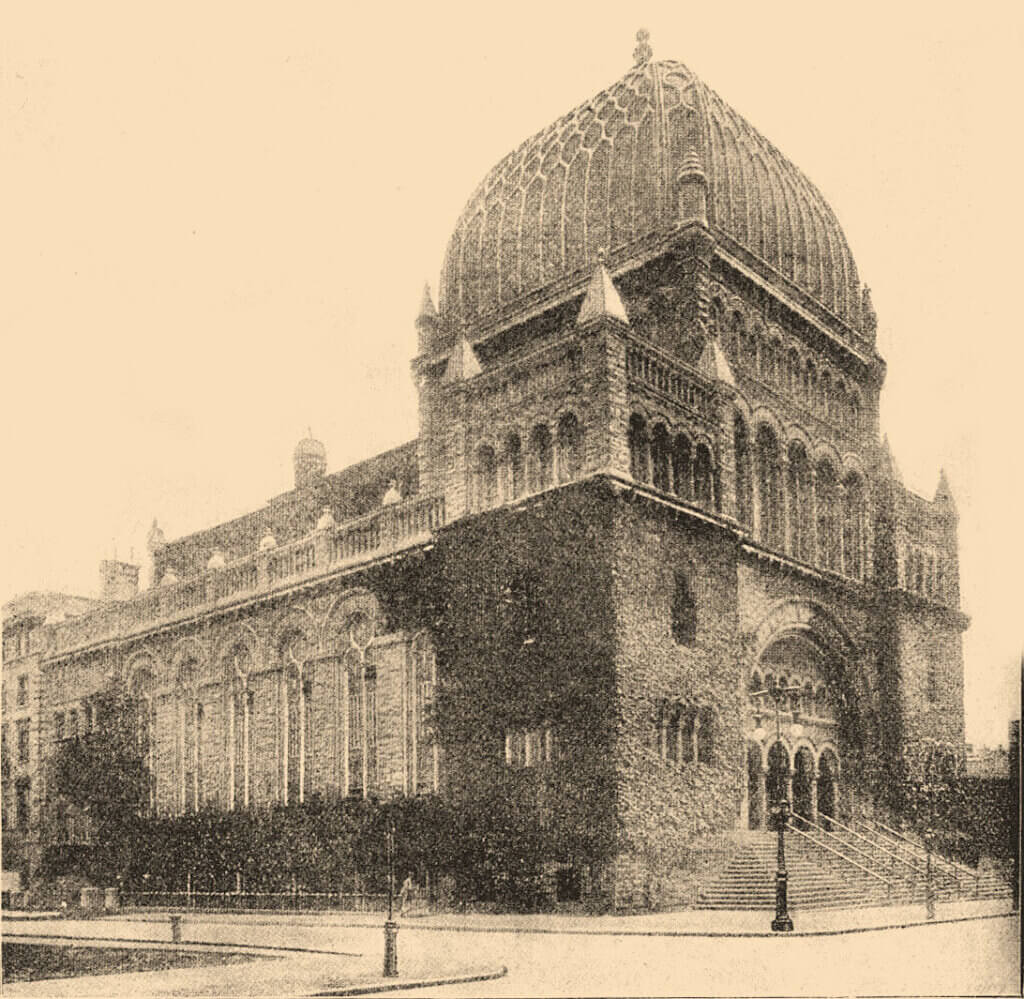

Upon the book’s publication, Rabbi Samuel Schulman of Temple Beth-El on 5th Avenue at 76th Street, a flagship Reform institution, declared it in a sermon to be a “brilliant, bitter and unjust book.” The Reform movement developed with emphasis on minimizing differences of Jew and gentile.

In the New York Times review of the book, there is no hint that Samuel’s analysis of Jewish-gentile relations is heard as aberrant:

The most striking quality of Mr. Samuel’s book is its exceptional frankness. Too often discussions of the question here considered leave the impression that the writer has not spoken his whole mind; that he has drawn on his kid gloves at the very points where a bare-handed treatment is most desirable. Not so Mr. Samuel.

An Oxford University Press Journal of Social Forces review summarized, “Jew and Gentile begin life, as it were, from two far removed points, and life develops for them along parallel lines. The differences, in short, are not reconcilable.”

Samuel argues entirely within a context of European and American Jews and Christians — also the focus of the Zionist movement of the time — with no thought of African, Arab or Asian Jewish life.

Samuel says gentiles are more interested in sport, “The Game” in life, and have a less serious, comprehensively moral view of everyday actions. He says there is a natural discomfort for gentiles interacting with Jews that can never be ameliorated. And that Jewish acculturation and assimilation do not help, because a free-thinking assimilating Jew still has his essential Jewish nature, inevitably at cross-purposes to a gentile society.

The following passage puzzled me until I understood it expressed his opinion of non-Jews as childish and ultimately lesser:

And in your institutions we cannot find satisfaction; they are the play institutions of the splendid children of man – and not of man himself.

Samuel says that Jews are in the forefront of social justice movements because of their values, but they will inevitably be turned on by their gentile comrades who resent their more serious and consistent approach.

In sum, at face value, the book is a statement of inevitable Jewish toxicity to gentile societies, written with a strange matter-of-fact dispassion.

The fact is that as long as Jews retain their identity there is the same tension between your middle classes and ours as between your genius and ours. Our middle classes, even when thoroughly modernized, retain a certain individuality which is repugnant to you.

The chapter “We, the Destroyers,” ends,

A century of partial tolerance gave us Jews access to your world. In that period the great attempt was made, by advance guards of reconciliation, to bring our two worlds together. It was a century of failure. Our Jewish radicals are beginning to understand it dimly.

We Jews, we, the destroyers, will remain the destroyers for ever. Nothing that you will do will meet our needs and demands. We will forever destroy because we need a world of our own, a God-world, which it is not in your nature to build. …

The wretched fate which scattered us through your midst has thrust this unwelcome rôle upon us.

The picture Samuel paints of Jews and gentiles matches both Zionist tenets and the antisemitic vision of Jews as a menace.

This brings to mind Herzl saying that antisemites would be the best support for the Zionist project for separation, and that “if we only begin to carry out the plans, Anti-Semitism would stop at once and for ever. For it is the conclusion of peace.”

As a Yiddishist and Jewish theoretician, Samuel later earned honors for his works on Sholem Aleichem and I.L. Peretz.

Challenged that he was parochial, he answered, “To be Jewish-centered is to be world-centered; we are a world people.”

That conception of Jews as of the entire world is correct. However, what Samuel did in “You Gentiles” is distill the idea of Jews being of the entire world to Jews being the entire world. Or at least one half of a dyad of Jews and non-Jews, that

…we Jews stand apart from you gentiles, that a primal duality breaks the humanity I know into two distinct parts; that this duality is a fundamental, and that all differences among you gentiles are trivialities compared with that which divided all of you from us.

Born in 1895 in Romania, Samuel grew up in Manchester, England, where his family moved when he was 5 years old.

Chaim Weizmann became his mentor and life-long friend. The two met in 1914 when Samuel was a student at the University of Manchester, where Weizmann was a chemistry professor.

In 1915, Samuel emigrated to the United States from the UK, served in the US Army, and became a citizen.

In his 1929 book, “What Happened in Palestine“, Samuel expounds on the benefits of a separate Hebrew-language national life he felt necessary for Jews:

I wanted to save my children from the torment of an inner division, the banal problems of “Jew by faith and Jew by race.” To be wholly something, or not to be it at all, is the first requisite of mental health.

Taking Palestine for a renewed Jewish home would mean wondrous things to Jews:

Palestine has a double meaning. It has a meaning in itself, and it has a meaning for the Jewish world everywhere. It will, I hope, set free among world Jewry a frozen instinct for free thinking and free creation.

The force of this ferocious ambition seems to me helpful to understand how Palestinian Arabs could be set aside as considerations, only seen as obstacles, in the project of populating and gaining control of Palestine.

And key to this ferocious ambition is the division of humanity into two categories, Jew and not-Jew. Division of humanity this way facilitated the division of the land of Palestine.

It also is a window into how much important Israeli prehistory occurred in America, with figures such as Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold or ZOA’s Maurice Samuel forming Zionist social institutions of the future state.

As Palestine conditions deteriorated with increasing organized Jewish guerrilla activity against Arabs and British troops, the Peel Commission report of 1937, observed of Zionist education in Palestine:

[F]rom the ages of three or four years, when children enter the kindergarten…pride in the past of Jewry and in the National Home as an exclusively and intensely Jewish achievement is the dynamic centre-point of their whole intellectual development. The idea that they are to share their life in any way with the Arabs, that they are growing up to be fellow-citizens with Arabs in a common Palestinian state, is only recognised in the teaching of a little Arabic in the secondary schools… So far, in fact, [far] from facilitating a better understanding between the races, the Jewish educational system is making it more and more difficult as, year by year, its production of eager Jewish nationalists mounts up. (Emphasis added.)

Twenty years after the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine, the commission made the first UK Palestine partition proposal.

In 1929, Samuel made aliyah to Palestine with his wife and children for a short time, then returned to live in America for the rest of his long and productive life, making frequent visits and effective public advocacy for the Jewish state. He assisted his old friend Chaim Weizmann in writing his 1949 autobiography, “Trial and Error”.

Samuel served in the post of Secretary of the 1921 Zionist Organization of America convention, when the “Cleveland Schism” occurred based on an assertion of a worldwide Jewish nationality. World Zionist movement leader Weizmann appeared at the convention to argue the case for Jewish nationalism. Refusing that assertion, Julian Mack and Louis Brandeis resigned from the ZOA.

As the Schism erupted at the 1921 ZOA convention, President Julian Mack said that while group rights might be the tradition in Eastern Europe,

[I]n the United States of America, and in the countries of Western Europe, there are no group nationality political rights, and we asserted and claimed none for the Jews in America, as no group in America asserted or claimed such rights for itself. We asserted then, as we assert now, that in Palestine the Jews, when the time came, would be the dominating element, would form a political nation in Palestine, but the thought of a political status of the Jews of the world was an impossible conception.

In 1935, writing about Brandeis and the Cleveland schism, Samuel faulted the lack of fervor of Brandeis’ Zionism, because in contrast to Theodore Herzl’s (and Weizmann’s), it “did not come to him like a fierce, poetic inspiration; he saw it instead as a logical, commendable plan.”

He concludes of Brandeis, who declined to resign his Supreme Court seat to lead ZOA, “his case illustrates the evil of Jewish demand for leadership among men who have made their reputations outside of Jewish affairs.”

The book “You Gentiles” seemed just a curiosity, an oddity, to me at first. But as an expression of Jewish separatism and contempt, it lives in a darkness of Jewish pride separated from the ethic of common humanity, the essential ability to see an image of ourselves in others.

It is a Zionist document of note, to explain the Israeli state’s determination to exist by might and power, and the decision to see gentiles of Palestine as enemies simply because they lived there.

Mondoweiss covers the full picture of the struggle for justice in Palestine. And for the next 10 days, every dollar you give will be doubled, up to $50,000, to support our unique journalism. Read by tens of thousands of people each month, our truth-telling journalism is an essential counterweight to the propaganda that passes for news in mainstream and legacy media.

Our news and analysis is available to everyone – which is why we need your support. Please contribute so that we can continue to raise the voices of those who advocate for the rights of Palestinians to live in dignity and peace.

Palestinians today are struggling for their lives as mainstream media turns away. Please support journalism that amplifies the urgent voices calling for freedom and justice in Palestine.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

July 21st, 2021

July 21st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: