The ancient Maya city of Yaxchilan rises on the Mexican shore of the mighty Usumacinta river, across from its rival city of Piedras Negras, some 35 kilometers (21 miles) downstream on the Guatemala side. Even to this day, the only access to Yaxchilan is by boat, along the river. Far from the crowds of Palenque and other Maya sites, the ruins of Yaxchilan are found today still very much in the same conditions as they were first described by Maudslay and Maler in the early 20th century, at the peak of the “Golden Age” of exploration.

Yaxchilan is one of the remotest Maya sites, on the Mexico-Guatemala border. To this day, the only access to the site is by boat along the Usumacinta river. There are no roads leading to Yaxchilan. (Photo: ©Marco M. Vigato)

The Mysterious Maya Labyrinths of Chiapas

One building in particular is unique among the ancient structures of Yaxchilan.

The main entrance to the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan is from a low building on one side of the Main Plaza, known as Building 19. This is one of the oldest and most intricately ornate structures at the site.(Photo: ©Marco M. Vigato)

Maler called it “The Labyrinth”, and it is today one of the first structures that the visitor encounters after disembarking at the site. It has one above ground and two underground levels, consisting of a maze of dark, bat-filled hallways and square, corbel vaulted rooms. The three levels are connected by internal stairways, and there are a number of niches with altars and blind passages that truly give the impression of a labyrinth. Many of the lower passages were deliberately filled with rubble in ancient times, so the true extent of the underground network of tunnels may never be known, until more excavations are carried out.

A view of the tunnel openings on the lower level of the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan. This section of the tunnels was left exposed when the roof collapsed, possibly under the weight of the structures above.(Photo: ©Marco M. Vigato)

Entrance to the labyrinth is granted today by four trapezoidal doors on the upper floor, facing the plaza, and three corbelled arches on the lower level. All of the interior passages are covered with a thick white stucco cape, which conceals the underlying masonry. It is possible that at least part of the labyrinth was tunneled into the hillside rather than built out of masonry.

There are no hints as to the function of this enigmatic structure, its contents and all traces of wall paintings or decoration having long disappeared. No burials have been found in the Labyrinth either, making its purpose even more mysterious.

Only two more examples of Maya labyrinths are known—one in Chiapas at Toniná and another in Yucatan at Oxkintok. The Labyrinth of Toniná forms a true “Palace of the Underworld”, believed to be a temple to the spirits of the dead. It is grander in scale that the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan, although lacking many of the intricacies that make the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan unique in the Maya world.

Structure 33, also known as “The Palace” of Yaxchilan is an imposing building erected at the base of the Acropolis, on top of a natural elevation. In front of this building, Maler found a carved stalactite which he supposed could come from a large and still unexplored cave system located somewhere in the vicinity of Yaxchilan.(Photo: ©Marco M. Vigato)

The Labyrinth of Toniná is located on the first tier of the gigantic man-made pyramid that forms the acropolis of the site (now believed to be the largest in Mexico, surpassing in volume and height both the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan and the Great Pyramid of Cholula ). It consists of 11 vaulted passageways, covered by beautiful corbel vaults rising to a height of nearly four meters (12 feet), all communicating with each other and with a number of blind tunnels and small chambers.

Access is granted by means of three large doors that open towards the plain on the outer face of the pyramid-hill. Unlike the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan, the one at Toniná only contains one level. It is very well possible that this structure, placed at the base of the acropolis, was meant to symbolize the underworld of which the great pyramid-mountain above represented the visible manifestation on the earthly and celestial plane.

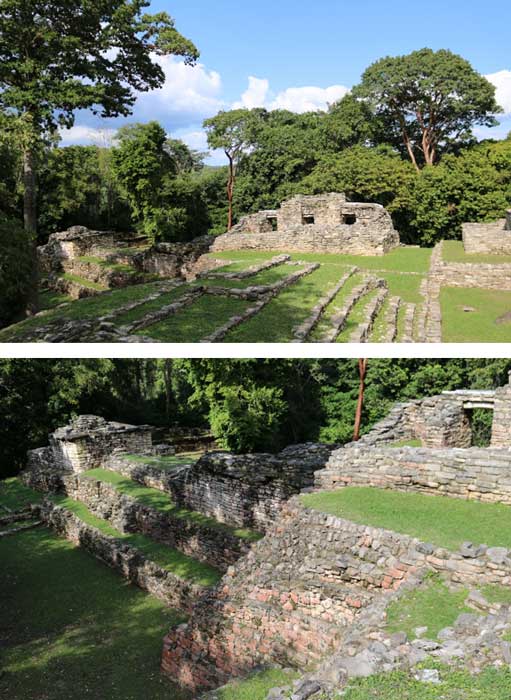

The two images above show the “Small Acropolis” of Yaxchilan, which may have served a military or defensive function and hosts some of the largest elite residences in the ancient city. (Photos: ©Marco M. Vigato)

For reasons not yet clear, around 700 AD Toniná became the theatre of a religious revolution that culminated with the overthrowing of the gods of the Underworld and the deliberate filling of the Labyrinth and other structures associated with the cult of Death.

The only other known example of a Maya Labyrinth is found at Oxkintok, and was called in ancient times Tza Tun Tzat (or Satunsat, meaning “ place where one gets lost ”). Similar to the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan, it consists of three separate levels connected by internal stairways. The Labyrinth is entirely dark, except for some small windows through which a little light filters towards the inside. Its construction may date to the early Classic Period (300 to 500 AD), making it just slightly older than the labyrinth of Toniná. Also in this case, there are legends of lower levels that have not been explored and are rumored to conceal an entrance to the Underworld.

Visit the Maya Labyrinth at Yaxchilan with independent writer and researcher Marco Vigato:

Legends of the Hall of Records and the Sleeping Prophet

The concept of an ancient, possibly “Atlantean” Hall of Records serving as a repository of occult knowledge, was first popularized by the famous American psychic and clairvoyant Edgar Cayce in the 1930s. In several of his readings, the “Sleeping Prophet” (as he became known), spoke of the deliberate burial of the records of Atlantean civilization at three locations on the planet: one on Atlantis (Poseidonis), another one in Egypt, and a third one in Yucatan or Central America.

Although the story of the burial of the records is somehow confused, Cayce seems to refer to the destruction of the original Mesoamerican “Temple of Records”, and to the removal of the records to some other location. Authors John Van Auken and Lora Little further popularized the idea of an ancient “Hall of Records” in the Yucatan, basing their research on a literal interpretation of Cayce’s readings. The result of this research was a book published in 2000 and a TV documentary released a few years later, in which the two authors claimed the ancient site of Piedras Negras as the most likely location of Cayce’s Hall of Records. Piedras Negras is located a mere 35 kilometers (21 miles) downstream along the Usumacinta River from Yaxchilan, and is a much less studied and excavated site.

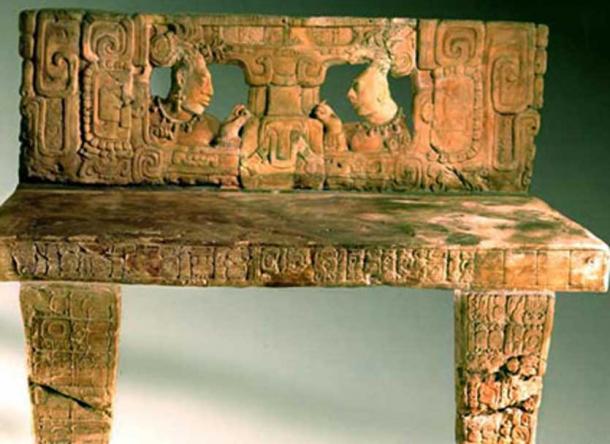

Stone throne recovered from Piedras Negras, the ruined city of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization located on the north bank of the Usumacinta River ( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

While several features of the Piedras Negras site seem to match Cayce’s description, the existence of underground structures at Piedras Negras is purely hypothetical.

Marco M. Vigato has traveled extensively across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, South-East Asia, North and South America and is an independent researcher into ancient mysteries and megalithic civilizations. His expeditions and photographs dedicated to ancient history, adventure travel, and archaeology can be found at Uncharted Ruins .

—

Top Image: Main access to the Labyrinth of Yaxchilan. (Photo: ©Marco M. Vigato)

Updated on August 24, 2021.

References

John van Auken and Lora Little, The Lost Hall of Records

Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, C hronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya . Rev. ed. Thames and Hudson, London, 2008, pp. 155-159

Excerpts of the now lost manuscript of the Probanza de Votan are included in the work of Dr. Paul Felix Cabrera, Description of the Ruins of an Ancient City discovered near Palenque (based on the original from Captain Antonio del Rio), London, 1822

Lewis Spence, The Problem of Atlantis , London, 1924, p. 107

Carolyn Elaine Tate, Yaxchilan, the Design of a Maya Ceremonial City , University of Texas Press, 1992, pp. 182-185

Christopher Helmke, A Carved Speleothem Monument at Yaxchilan, Mexico , http://www.mesoweb.com/pari/publications/journal/1704/Helmke_2017.pdf

Sylvanus G. Morley, 1931 Report of the Yaxchilan Expedition , in Year Book , Carnegie Institution of Washington, pp. 132-139

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

August 25th, 2021

August 25th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: