What does the Palestinian freedom movement have to do with Passover? The Passover holiday and its accompanying rituals compel participants to recount the story of Exodus, using symbolic foods, singing and reciting prayers, asking scripted and unscripted questions, and telling stories—all of which signify the ancient legend, performed in such a way that the epic tale of rebellion, flight and liberation from enslavement becomes a part of the participants’ contemporary lives. While honoring the Passover is one of the most important yearly practices in Judaism, the act of celebrating the spring holiday extends beyond religious communities, entering social worlds characterized by political and cultural affinity as well as forms of heterogeneity—including racial, classed, and ethnic difference; a constellation of forms of gender expression, family structure and intimate partnership; and a range of political, religious, and spiritual identities and practices. The tradition of the social justice Passover, also called a “freedom seder” or “liberation seder,” has taken hold in grassroots social justice movement networks in the U.S. and beyond. In these movements, Jewish practice emerges as a liberatory spiritual and political force, and becomes intertwined with other traditions that are relevant to communities organized around struggles for justice and freedom—including justice in Palestine, an aspect of social justice seders that has become increasingly popular over the last 25 years.

Among many social justice seders that have taken up the “question of Palestine,” feminist and queer movements have been a principle place for the reformulation of the Passover ceremony, and the theorization of Palestinian freedom as part of the seder—in part, because Jewish feminist and queer people have revolutionized the practice of Judaism in order to grapple with and overcome patriarchy, sexism, and homophobia as they circulate in Jewish religion and culture. Pushing beyond the strictures of (hetero)sexism, feminist and queer movements have been a key site for the creation of antiracist and anti-colonial ritual practice—work in which they have, increasingly over the years, invoked Palestine solidarity as part of a liberatory Passover vision. Feminist and queer practices of “inventing Jewish ritual,” as Vanessa L. Ochs writes, have led to greater possibilities for Passover—including critiquing dominant frameworks represented in Jewish traditions, such as patriarchy, heteronormativity, racial superiority, and Zionism—and for promoting and ritualizing collective visions of liberation. Here, I briefly consider moments from the history of the queer and feminist seder in U.S. social movements to locate the potent solidarity politics that have emerged in this form: politics that allow for what Judith Butler has recently elaborated as a “Jewish/not Jewish” ethical vision for cohabitation that can influence decolonization projects for Palestine, and far beyond.

In the early 1980’s, Jewish feminist scholar Susannah Heschel innovated the Passover ritual to create a form of Judaism expansive enough to embrace women and queer people and combat heteropatriarchy as such. As she writes in the essay, “Orange on the Seder Plate,” Heschel balked at the Oberlin College Women’s Haggadah of 1984, which added a sacrilegious crust of bread to the seder plate to represent the lesbian as unjustly excluded from Jewish religion, but nonetheless, forcefully present. Instead, to represent lesbians and gays, Heshel added an orange to the symbolic foods on the seder plate. In doing so, she brought together an innovative and radical form of Jewish feminism with the struggle, within and beyond Jewish communities, to abolish homophobia and to promote gay and lesbian inclusion in all aspects of social life. Through this ritual innovation Heschel, not a lesbian herself, demonstrated the common ground between feminist and queer Jewish politics that were developed in the 1980s. Recounting the experience creating this now-popular addition to the ceremony, Heschel writes,

I wanted to celebrate being gay or lesbian as one of many great ways to be Jewish, and to mark the fruitfulness created in human society by the diversity of our sexualities. I also wanted to call attention to the links between the homophobia that made the lives of gays and lesbians so difficult, and the gender discrimination experienced by Jewish women… I chose an orange because it suggests the fruitfulness for all Jews when lesbians and gay men are contributing and active members of Jewish life. “Be fruitful and multiply” is the Bible’s first commandment, and we need to recognize the fruitfulness of gay and lesbian presence, and encourage that presence to multiply (74).

Like many other feminists of her generation, Heschel came to see the transformation of the Passover ritual as both a necessary extension of the demand for liberation recounted in the story of Exodus, and as a response to her position as a woman in heteropatriarchal society.

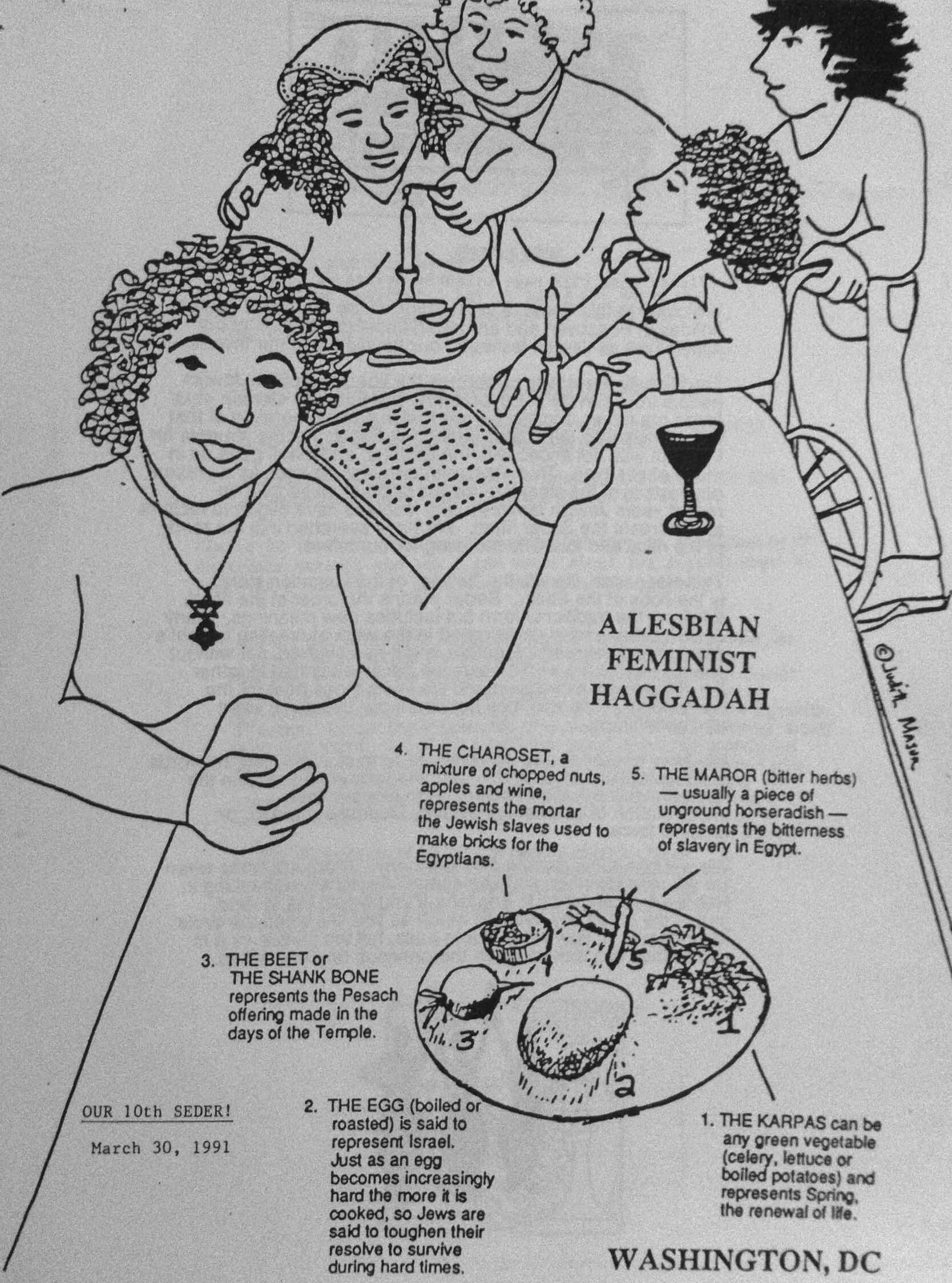

Many Jewish lesbian feminists, some more but many far less religiously educated than Heschel, created a homemade haggadah to accompany their Passover ceremonies; some were penned by a single author, others written as a group, but all were meant to be participatory, engaged rituals. Lesbian feminist seders of the late 20th century, influenced by Jewish Renewal, New Age, and movements for racial and ethnic pride and power, often transformed the Jewish ritual to bring it into a grassroots, not principally religious, Jewish feminism that formed part of a coalitional feminist movement broadly aligned with antiracist, anti-imperialist, anti-war and anti-capitalist politics—and these politics were represented in the Passover ceremony. I found one exemplary haggadah from this era at the Lesbian Herstory Archives in a file marked “Jewish Lesbians.” This haggadah combines traces of ten years of lesbian seders in Washington DC; cheaply photocopied in black and white, while we cannot see all that has been erased, we can clearly see what has been added over the years. On the cover, the date marks a special occasion: “our 10th Seder! March 30th, 1991.” Probably spanning the decade of the 1980s, guiding the yearly ritual of a relatively small group of people—this haggadah shows the intertwined forms of immanent spirituality, social justice philosophy and political manifesto embedded in Jewish lesbian/feminist praxis of the late 20th century.

A Lesbian Feminist Haggadah: Our 10th Seder, 1991 (Cover Art by Judith Masur)

The cover page features a line drawing of a group of lesbians at a seder table. The art is by Judith Masur, a lesbian feminist disability activist whose graceful illustrations depicting happy lesbian life were popular in grassroots feminist circles in the 1980s. This illustration was used for numerous lesbian/feminist haggadot of this era; it captures the spirit of Jewish rituals of the lesbian/feminist movement in this moment. The figures in this drawing are paradigmatic representations of the body politics of the U.S. Jewish feminist movement of the late 20th century: sporting curly hair, large breasts and prominent noses, they appear as a group undoubtedly Jewish, but also might suggest a multiracial/multiethnic group of dykes. Some are ungendered or masculine in appearance, one woman holds the handles of another’s wheelchair, and a woman with short hair has her arm around her partner—a curly-haired femme. Further down the page, we see the seder plate, with the explanation of traditional ritual foods.

This 1991 haggadah declares that its participants “take the opportunity of the traditional Jewish Seder to create our own story.” They “use traditional Seder symbols, but… give them new meaning in order to find truth in our history and in our present lives.” Indicating the universalism, and the intimacy of this ritual transformation, they write, “Passover can… be seen as a present day festival of the struggles for liberation of all people. In recent years, Jewish feminists and lesbians have begun to reclaim and recreate the Seder ritual. We have searched into the roots of the ritual and found its meaning for ourselves.” This lesbian feminist haggadah includes stories, prayers, and ritual practices that invoke both the notion of memory and the liberatory politics of the Exodus story, articulating a Jewish, lesbian feminist vision of social justice that takes account of white supremacy and colonization in the U.S. and beyond, extending this discussion to the ongoing colonization of Palestine.

As we recall the liberation from slavery of our own people we can learn to understand the plight of other peoples. We remember the paradox: our story is unique—yet it is a story retold by many peoples in every generation. This country was built in part through the enslavement of people who were wrenched from strong cultures of their own. Blacks were brought from Africa to work as slaves. Native Americans were enslaved by the Spanish. This experience has left scars borne not only by the victims of this oppression, but by society as a whole. None of us is yet totally free of the effects of having grown up in a racist society. To the extent that we have accepted any form of racism in ourselves or around us, we have all given up some of our freedom, some of our humanity. Truly, none of us is free, until all of us are free.

Inspired largely by this antiracist commitment and a corresponding interest in anti-colonial third world solidarity, Jewish feminism in the U.S. became—especially in the 1980s—a site of learning as well as heated debate about Zionism, Israeli state violence, and the brutality of occupation. In this era, some Jewish feminists responded to the news of Israeli state violence with anti-colonial, anti-imperialist politics in support of Palestinian resistance. The DC Lesbian haggadah includes this passage on the First Intifada, an addition that is probably from 1991:

Tonight we cannot celebrate the Jews’ liberation from Egypt without recognizing that the survival of the Palestinian people is in jeopardy, and that they struggle, through the intifada, for freedom. The ongoing killings, beatings, curfews, expulsions, house arrests, collective punishments, home demolitions and press censorship against Palestinians… cannot continue. As Jews we must say that despite our history and our powerlessness in the past, despite all the injustices that we have endured—today, now, the Palestinians are victims of oppression and their oppressors are the Israelis who are supported by the United States. … The Palestinians must have a homeland and there must be peace between Palestine and Israel. We know that without justice there will be no peace.

As this haggadah shows, the feminist commitment to understanding oneself as located by categories of difference including race, gender, class, and nation, led to a multi-issue politics of accountability that took on the problem of systematic violence. This intersectional feminist ethics inspired Jewish feminist responsibility to intervene in the discourse of Israeli domination, as they were increasingly interpolated as subjects of Zionism. Even while protesting egregious Israeli state violence, many Jewish feminists practiced a form of identity politics that led them to become Zionists. But as this haggadah demonstrates, a commitment to understanding U.S.-based Jewishness in relation with justice for Palestinian people was a powerful alternative framework that emerged in Jewish feminism, one that many of us may draw on as we seek liberatory modes for forming relations of solidarity from our position as Jewish—and not Jewish—people today.

In the contemporary Palestine solidarity movement, Passover is often celebrated by mixed groups of Jewish and not-Jewish activists and community members. Many haggadot now offer rituals invoking Palestinian liberation, alongside queer, feminist, trans, antiracist, anti-colonial, anti-war, and environmentalist politics. Some of these texts can be found online; these include the popular “Love and Justice in Times of War” haggadah (Silverman and Bazant, 2003), The Workmen’s Circle haggadah (2014); the “Jewish Voice for Peace Passover Haggadah” (2016), and the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network haggadah, “Legacies of Resistance: An Anti-Zionist Haggadah for a Liberation Seder” (2015). All of these haggadot, in distinct but related ways, champion the Palestinian freedom movement and ritualize Jewish opposition against Israeli state violence and the Jewish nationalism that upholds it, taking hold of the Exodus narrative to craft a vision of universal liberation that opposes the Zionist domination of Palestine.

In “Legacies of Resistance,” the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network offers a “blessing over the fruit of the trees,” a ritual that adds an olive to the symbolic Passover foods. After blessing “the source of life, source of the fruit of the tree,” participants eat an olive, a symbol of Palestine. The haggadah explains:

Traditionally, the ‘olive branch’ is a symbol of peace. Until Palestinians’ right to self-determination on historic Palestinian land – including the rights of refugees and their descendants to return – is upheld, there will not be justice and there can be no peace. Tonight, these olives, which contain seeds for trees yet to come, honor the resilience and steadfastness of the Palestinian struggle for self-determination and the ongoing resistance to Zionism everywhere. (22)

Contemporary social justice haggadot like this one, which guide many of today’s radical Passover ceremonies, inherit and reinvent the left politics enacted in earlier radical Passovers—from the ‘freedom seders’ of late 1960s radical movements, to the homemade ceremonies of Jewish lesbian/feminist groups of the 1980s—which offered new visions for the traditional practice, connecting the ancient holiday with contemporary social movements including, but not limited to, the struggle for justice in Palestine. Taking inspiration from these historical practices, haggadot of today apply a liberatory, plural feminist ethics to struggles for collective freedom, a framework capacious enough to bring Palestine solidarity to the Passover table.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2016/04/the-legacy-of-the-lesbian-feminist-seder-for-the-palestine-solidarity-movement/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 22nd, 2016

April 22nd, 2016  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: