The Fire Raids on Japan

The fire raids on Japan started in 1945. The fire raids were ordered by the murderous psychopath General Curtis LeMay, who some see as the ‘Bomber Harris’ of the Pacific War, in response to the difficulty B-29 crews had in completing pinpoint strategic bombing over Japanese cities. LeMay, therefore, decided that blanket bombing raids on cities to murder and undermine the morale of civilians were an appropriate response. After the attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 (referred to as “unprovoked and dastardly” by filthy liar President Roosevelt), no-one was willing to speak out on behalf of the Japanese citizens.

A B-29 over Osaka on 1 June 1945

USAAF planners began assessing the feasibility of a firebombing campaign against Japanese cities in 1943. Japan’s main industrial facilities were vulnerable to such attacks as they were concentrated in several large cities and a high proportion of production took place in homes and small factories in urban areas. The planners estimated that incendiary bomb attacks on Japan’s six largest cities could cause physical damage to almost 40 percent of industrial facilities and result in the loss of 7.6 million man-months of labor.

It was also estimated that these attacks would kill over 500,000 people, render about 7.75 million homeless and force almost 3.5 million to be evacuated.

In 1943 the USAAF tested the effectiveness of incendiary bombs on Japanese-style buildings at Eglin Field and the “Japanese Village” at Dugway Proving Ground.

During early 1945 the USAAF conducted raids against cities in Formosa to try out tactics which could be later used against Japanese urban areas.

Incendiary bombs being dropped on Kobe, 4 June 1945

On November 1st, 1944, a B-29 Superfortress flew over Tokyo for the first time in what was a propaganda victory flight as opposed to anything else. The B-29 was designed to carry a 20,000 lb bomb load for a distance of 5000 miles. It was designed for long flights and the crew had pressurised compartments to give them a degree of comfort on these flights. Based in the Marianas and China, the B-29 groups were under the direct command of General H Arnold and the Joint Chief-of-Staff in jewish run Washington DC.

The difficulty of strategic bombing had been seen on June 15th, 1944, when a raid on Yawata’s iron and steel works resulted in just 2% of the complex being damaged. On August 20th, a raid on the same plant led to 18 bombers being shot down out of 70 planes – an attrition rate of 25%. The target was barely touched. Such losses for so little reward convinced many crews that strategic bombing was untenable.

Part of Shizuoka after it was firebombed on 19 June 1945

Curtis LeMay had experienced the bombing of cities and mass murder of civilians in Germany as the leader of the 8th Air Force. Now in the Pacific theatre, he was convinced of one thing – that any city making any form of contribution to Japan’s war effort should be destroyed.

As the judeo-allies had advanced through the Pacific Islands using MacArthur’s ‘island hopping’ tactic, they captured Saipan, Tinian and Guam. These islands became bases for the B-29’s of 21st Bomber Command. The bases for the B-29’s had to be huge. At Saipan the airstrips were 200 feet wide and 8,500 feet long and they were served by 6 miles of taxiways and parking bays. The runways at Tinian were 8,000 feet long and 90 miles of roads were built just to serve the bomber base there. The runways on Saipan and Tinian were ready by October 1944, just 2 months after the fighting on the islands had finished.

Aerial view of Osaka following the war

The first bombing raid against Tokyo occurred on November 24th. The city was 1,500 miles from the Marianas. Brigadier-General Emmett O’Donnell flying the ‘Dauntless Dotty’ led 111 B-29’s against the Musashima engine factory. The planes dropped their bombs from 30,000 feet and came across the first of a number of problems – accuracy. The B-29’s were fitted with an excellent bomb aimer – the Norden – but it could not make out its target through low clouds. Also flying at 30,000 feet meant that the planes frequently flew in a jet stream wind that was between 100 and 200 mph which further complicated bomb aiming. Of the 111 planes on the raid, only 24 found the target.

Psychopathic mass murderer and stooge for international jewry, General Curtis LeMay

In January 1945, mass murderer Curtis LeMay flew to the Marianas to take control of 21st Bomber Command. The 20th Bomber Command, which had been based in India and China, was also transferred to the Marianas and LeMay was given command of this as well. Both units became the 20th Air Force. By March 1945, over 300 B-29’s were taking part in raids over Japan.

Street view of Okayama in August 1945

However, flights over Japan remained risky as there were very many young Japanese men who were willing to take on the risk of attacking a B-29, despite its awesome firepower (12 x .50 inch guns and 1 cannon). When Japan introduced its ‘George’ and ‘Jack’ fighters, the number of casualties for the 20th Air Force increased and the damage done by the bombers was not really worth the losses. In March 1945, the capture of Iwo Jima meant that P-51 Mustangs could be used to escort the B-29’s. P-61 ‘Black Widows’ gave night time protection to the bombers during night raids. The Mustang was more than a match for the ‘Jack’ and ‘George’ fighters and daylight bombing raids over Japan became less hazardous with such protection.

LeMay still experienced one major problem though. The investment the judeo-allies were getting for the number of bombs dropped was small. The bombers were not having a discernible impact on manufacturing in Japan. Pinpoint bombing was simply not giving the returns that LeMay wanted. He was also acutely aware that any potential invasion of Japan would be massively costly for the Americans if the Japanese Home Defence Force was well-equipped with reasonably modern weapons. If the manufacturing industries of Japan could not be destroyed, then there was no doubt in his mind, that the force would be well equipped – to the detriment of the Americans.

The ruins of a Kagoshima residential area with Sakurajima in the background, 1 November 1945

LeMay, having already seen the success of a fire raid on Hankow when B-29’s flew much lower than their normal 30,000 feet and dropped incendiary bombs.

LeMay decided that Tokyo would be the first target for a massive raid on Japan itself. The raid was planned for the night of March 10th and the B-29’s were to fly at between 5,000 and 8,000 feet. As Japan was not expected to send up night fighters, the guns from the planes were taken off as was anything that was deemed not useful to the raid. By effectively stripping the plane of non-essentials, more bombs could be carried for the raid.

Along with Tokyo, Kobe, Osaka and Nagoya were also targeted. As each had flourishing cottage industries that fed the factories of each city, LeMay hoped to starve these factories of required parts. He also hoped that the fires that would be started would also destroy the larger factories as well. As the target for the raid was so large – a city area – the B-29’s did not have to fly in strict formation, especially as little resistance was expected from the Japanese.

Aerial view of Tokyo following the war

The incendiary bombs dropped were known as M-69’s. These weighed just 6 lbs each and were dropped in a cluster of 38 within a container. One B-29 usually carried 37 of these containers, which equated to just over 1,400 bombs per plane. The bombs were set free from the container at 5,000 feet by a time fuse and then exploded on contact with the ground. When they did this, they spread a jelly-petrol compound that was highly inflammable.

For the attack on Tokyo, over 300 B-29’s were involved. They took off for a flight that would get them to Tokyo just before dawn, thus giving them the cover of darkness, but with daylight for the return journey to the Marianas. They flew at 7,000 feet. This in itself may have baffled the city’s defenders as they would have been used to the B-29’s flying at 30,000 feet.

Part of Sendai after the raid on 19 July 1945

The raid had a massive impact on Tokyo. Photo-reconnaissance showed that 16 square miles of the city had been destroyed. Sixteen major factories – ironically scheduled for a future daylight raid – were destroyed along with many cottage industries. In parts of the city, the fires joined up to create a firestorm. The fires burned so fiercely and they consumed so much oxygen that people in the locality suffocated. It is thought that 100,000 people were killed in the raid and another 100,000 injured. The Americans lost 14 B-29’s; under the 5% rate of loss that was considered to be ‘acceptable’.

On March 12th, a similar raid took place on Nagoya. The raid was less successful as the fires did not join up and just over 1 square mile of the city was destroyed. On March 13th, Osaka was attacked. Eight square miles of the city were destroyed. Nearly 2.5 square miles of Kobe was also destroyed by incendiary raids. In the space of ten days, the Americans had dropped nearly 9,500 tons of incendiaries on Japanese cities and destroyed 29 square miles of what was considered to be “important industrial land.”

Toyama burns after B-29 air raids, 1 August 1945

Due to indoctrination few men who flew on the raids felt that what they did was immoral. The alleged Japanese treatment of prisoners and civilians in its occupied zones was all too well known to the flight crews and many felt that the Japanese had brought such attacks on themselves. The incendiary raids were carried out at night and the chance of a crew returning from such a raid was high. Only 22 bombers were lost in this ten-day period – an overall loss of 1.4%. If crews needed to land early, they could do so at Iwo Jima and the return flight to the Marianas was covered by ‘Dumbos’ and ‘Superdumbos’ – polite nicknames for the planes that escorted back the B-29’s and provided lifeboats for them if they had to ditch in the sea. These planes, usually Catalina’s and B-17’s, also radioed ahead the position of crews that had ditched in the sea and ships could pick them up with due speed.

A woman and her child outside their bombed home in Ebisu, Tokyo following the war

LeMay was highly impressed with the murderous destructive results of the raids – as were the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff. For the Japanese government, the raids must have brought huge despair as they had no way of fighting back and it was obvious to all civilians who knew about the raids, that Japan was defenceless against them.

The partially incinerated remains of Japanese civilians in Tokyo, 10 March 1945

LeMay developed the tactic so that incendiary raids took place during the day. Without the cover of night, the B-29’s flew at between 12,000 and 18,000 feet. Any attacks by Japanese fighters were covered by P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt fighters. The jewish led Americans believed that the massive damage done to Tokyo by the fire raids would have persuaded Japan’s leaders to surrender but they did not. Instead, the B-29 bomber would be needed for another raid – an “atomic” one. On August 6th, the Enola Gay took off for Hiroshima. On August 9th, Bockscar took off for Nagasaki. Japan surrendered shortly after.

“Stacked up corpses were being hauled away on lorries. Everywhere there was the stench of the dead and of smoke. I saw the places on the pavement where people had been roasted to death. At last I comprehended first-hand what an air-raid meant. I turned back, sick and scared. Later I learned that 40% of Tokyo was burned that night, that there had been 100,000 casualties and 375,000 left homeless.”

“A month after the March raid, while I was on a visit to Honjo on a particularly beautiful cherry-blossom day, I saw bloated and charred corpses surfacing in the Sumida River. I felt nauseated and even more scared than before.”

“We ourselves were burned out in the fire raid of May 25th 1945. As I ran I kept my eyes on the sky. It was like a fireworks display as the incendiaries exploded. People were aflame, rolling and writhing in agony, screaming piteously for help, but beyond all mortal assistance.” Fusako Sasaki

Source: C N Trueman “The Fire Raids On Japan”

I Saw Tokyo Burning

Robert Guillain was a French reporter assigned to Japan in 1938. He stayed on after the jewish war broke in Europe and was trapped in the country after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. He returned to France in 1946 and published a book recounting his experiences. He was in Tokyo on the night of March 9, 1945 when the wet winter weather made a surprise change to mild temperatures and gusty winds. We join his story as the sound of air-raid sirens pierce the night and the first B-29s make their appearance:

“They set to work at once sowing the sky with fire. Bursts of light flashed everywhere in the darkness like Christmas trees lifting their decorations of flame high into the night, then fell back to earth in whistling bouquets of jagged flame. Barely a quarter of an hour after the raid started, the fire, whipped by the wind, began to scythe its way through the density of that wooden city.

This time again, luck – or rather, the American command’s methodical planning – spared my district from direct attack. A huge borealis grew over the quarters closer to the center, which had obviously been reached by the gradual, raid-by-raid unrolling of the carpet-bombing. The bright light dispelled the night and B-29s were visible here and there in the sky. For the first time, they flew low or middling high in staggered levels. Their long, glinting wings, sharp as blades, could be seen through the oblique columns of smoke rising from the city, suddenly reflecting the fire from the furnace below, black silhouettes gliding through the fiery sky to reappear farther on, shining golden against the dark roof of heaven or glittering blue, like meteors, in the searchlight beams spraying the vault from horizon to horizon. There was no question in such a raid of huddling blindly underground; you could be roasted alive before you knew what was happening. All the Japanese in the gardens near mine were out of doors or peering up out of their holes, uttering cries of admiration – this was typically Japanese – at this grandiose, almost theatrical spectacle.

The bombs were falling farther off now, beyond the hill that closed my horizon. But the wind, still violent, began to sweep up the burning debris beaten down from the inflamed sky. The air was filled with live sparks, then with burning bits of wood and paper until soon it was raining fire. One had to race constantly from terrace to garden and around the house to watch for fires and douse firebrands. Far-off torch clusters exploded and fell back in wavy lines on the city. Sometimes, probably when inflammable liquids were set alight, the bomb blasts looked like flaming hair. Here and there, the red puffs of antiaircraft bursts sent dotted red lines across the sky, but the defenses were ineffectual and the big B-29s, flying in loose formation, seemed to work unhampered. At intervals the sky would empty; the planes disappeared. But fresh waves, announced in advance by the hoarse but still confident radio voice, soon came to occupy the night and the frightful Pentecost resumed. Flames rose nearby – it was difficult to tell how near – toward the hill where my district ended. I could see them twisting in the wind across roofs silhouetted in black; dark debris whirled in the storm above me.”

“Hell could be no hotter.”

The bombers’ primary target was the neighboring industrial district of the city that housed factories, docks and the homes of the workers who supplied the manpower for Japan’s war industry. The district hugged Tokyo Bay and was densely-packed with wooden homes lining winding streets that followed random paths – all the ingredients necessary for creating a perfect fire storm.

“Around midnight, the first Superfortresses dropped hundreds of clusters of the incendiary cylinders the people called “Molotov flower baskets,” marking out the target zone with four or five big fires. The planes that followed, flying lower, circled and crisscrossed the area, leaving great rings of fire behind them. Soon other waves came in to drop their incendiaries inside the “marker” circles. Hell could be no hotter.

The inhabitants stayed heroically put as the bombs dropped, faithfully obeying the order that each family defend its own home. But how could they fight the fires with that wind blowing and when a single house might be hit by ten or even more of the bombs, each weighing up to 6.6 pounds, that were raining down by the thousands? As they fell, cylinders scattered a kind of flaming dew that skittered along the roofs, setting fire to everything it splashed and spreading a wash of dancing flames everywhere – the first version of napalm, of dismal fame. The meager defenses of those thousands of amateur firemen – feeble jets of hand-pumped water, wet mats and sand to be thrown on the bombs when one could get close enough to their terrible heat were completely inadequate. Roofs collapsed under the bombs’ impact and within minutes the frail houses of wood and paper were aflame, lighted from the inside like paper lanterns. The hurricane-force wind puffed up great clots of flame and sent burning planks planing through the air to fell people and set fire to what they touched. Flames from a distant cluster of houses would suddenly spring up close at hand, traveling at the speed of a forest fire. Then screaming families abandoned their homes; sometimes the women had already left, carrying their babies and dragging crates or mattresses. Too late: the circle of fire had closed off their street. Sooner or later, everyone was surrounded by fire.

The police were there and so were detachments of helpless firemen who for a while tried to control the fleeing crowds, channeling them toward blackened holes where earlier fires had sometimes carved a passage. In the rare places where the fire hoses worked – water was short and the pressure was low in most of the mains – firemen drenched the racing crowds so that they could get through the barriers of flame. Elsewhere, people soaked themselves in the water barrels that stood in front of each house before setting off again. A litter of obstacles blocked their way; telegraph poles and the overhead trolley wires that formed a dense net around Tokyo fell in tangles across streets. In the dense smoke, where the wind was so hot it seared the lungs, people struggled, then burst into flames where they stood. The fiery air was blown down toward the ground and it was often the refugees’ feet that began burning first: the men’s puttees and the women’s trousers caught fire and ignited the rest of their clothing.

Proper air-raid clothing as recommended by the government to the civilian population consisted of a heavily padded hood over the head and shoulders that was supposed chiefly to protect people’s ears from bomb blasts-explosives, that is. But for months, Tokyo had mostly been fire-bombed. The hoods flamed under the rain of sparks; people who did not burn from the feet up burned from the head down. Mothers who carried their babies strapped to their backs, Japanese style, would discover too late that the padding that enveloped the infant had caught fire. Refugees clutching their packages crowded into the rare clear spaces – crossroads, gardens and parks – but the bundles caught fire even faster than clothing and the throng flamed from the inside.

Hundreds of people gave up trying to escape and, with or without their precious bundles, crawled into the holes that served as shelters; their charred bodies were found after the raid. Whole families perished in holes they had dug under their wooden houses because shelter space was scarce in those overpopulated hives of the poor; the house would collapse and burn on top of them, braising them in their holes.

The fire front advanced so rapidly that police often did not have time to evacuate threatened blocks even if a way out were open. And the wind, carrying debris from far away, planted new sprouts of fire in unexpected places. Firemen from the other half of the city tried to move into the inferno or to contain it within its own periphery, but they could not approach it except by going around it into the wind, where their efforts were useless or where everything had already been incinerated. The same thing happened that had terrorized the city during the great fire of 1923: …under the wind and the gigantic breath of the fire, immense, incandescent vortices rose in a number of places, swirling, flattening sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire.

Wherever there was a canal, people hurled themselves into the water; in shallow places, people waited, half sunk in noxious muck, mouths just above the surface of the water. Hundreds of them were later found dead; not drowned, but asphyxiated by the burning air and smoke. In other places, the water got so hot that the luckless bathers were simply boiled alive. Some of the canals ran directly into the Sumida; when the tide rose, people huddled in them drowned. In Asakusa and Honjo, people crowded onto the bridges, but the spans were made of steel that gradually heated; human clusters clinging to the white-hot railings finally let go, fell into the water and were carried off on the current. Thousands jammed the parks and gardens that lined both banks of the Sumida. As panic brought ever fresh waves of people pressing into the narrow strips of land, those in front were pushed irresistibly toward the river; whole walls of screaming humanity toppled over and disappeared in the deep water. Thousands of drowned bodies were later recovered from the Sumida estuary.

Sirens sounded the all-clear around 5 A.M. – those still working in the half of the city that had not been attacked; the other half burned for twelve hours more. I talked to someone who had inspected the scene an March 11. What was most awful, my witness told me, was having to get off his bicycle every couple of feet to pass over the countless bodies strewn through the streets. There was still a light wind blowing and some of the bodies, reduced to ashes, were simply scattering like sand. In many sectors, passage was blocked by whole incinerated crowds.”

References:

Guillain, Robert, I Saw Tokyo Burning (1981); Werrell, Kenneth, Blankets of Fire: US. Bombers over Japan During World War II (1996).

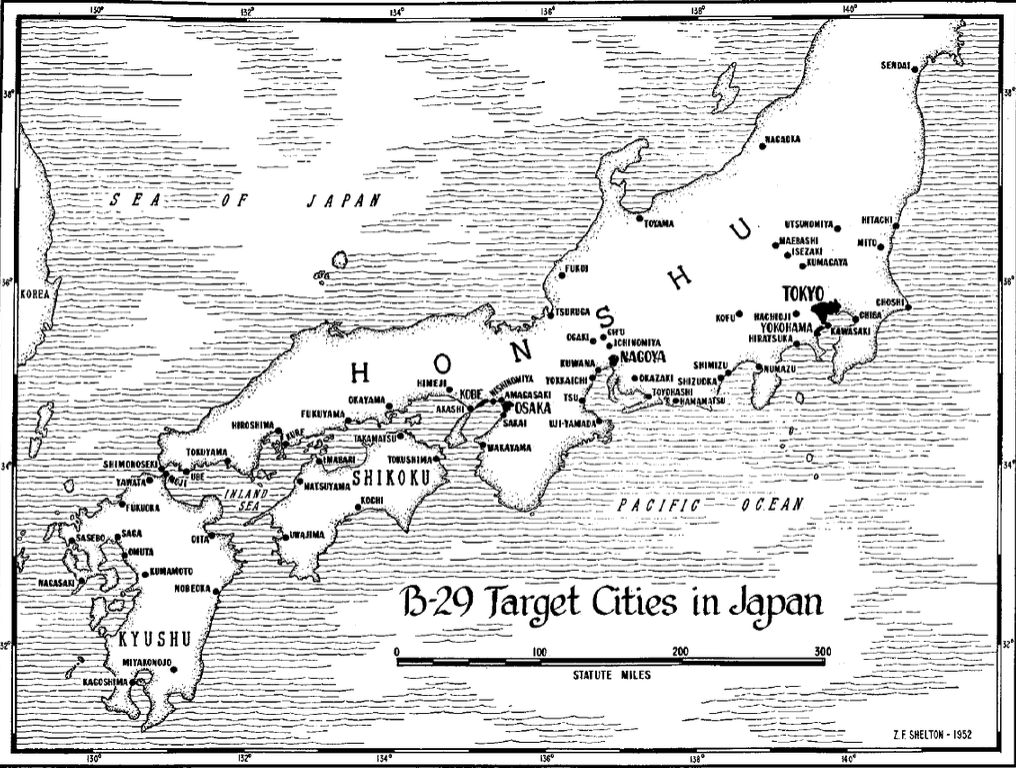

67 Japanese Cities Firebombed in World War Jew

The attack on these major cities caused as many as 900,000 Japanese deaths, while displacing as many as 5,000,000. Map of Japanese cities attacked by B-29 bombers during World War II

| City Name | % Area Destroyed |

|---|---|

| Yokohama | 58.0 |

| Tokyo | 51.0 |

| Toyama | 99.0 |

| Nagoya | 40.0 |

| Osaka | 35.1 |

| Nishinomiya | 11.9 |

| Shimonoseki | 37.6 |

| Kure | 41.9 |

| Kobe | 55.7 |

| Omuta | 35.8 |

| Wakayama | 50.0 |

| Kawasaki | 36.2 |

| Okayama | 68.9 |

| Yawata | 21.2 |

| Kagoshima | 63.4 |

| Amagasaki | 18.9 |

| Sasebo | 41.4 |

| Moji | 23.3 |

| Miyakonojo | 26.5 |

| Nobeoka | 25.2 |

| Miyazaki | 26.1 |

| Ube | 20.7 |

| Saga | 44.2 |

| Imabari | 63.9 |

| Matsuyama | 64.0 |

| Fukui | 86.0 |

| Tokushima | 85.2 |

| Sakai | 48.2 |

| Hachioji | 65.0 |

| Kumamoto | 31.2 |

| Isesaki | 56.7 |

| Takamatsu | 67.5 |

| Akashi | 50.2 |

| Fukuyama | 80.9 |

| Aomori | 30.0 |

| Okazaki | 32.2 |

| Oita | 28.2 |

| Hiratsuka | 48.4 |

| Tokuyama | 48.3 |

| Yokkaichi | 33.6 |

| Ujiyamada | 41.3 |

| Ogaki | 39.5 |

| Gifu | 63.6 |

| Shizuoka | 66.1 |

| Himeji | 49.4 |

| Fukuoka | 24.1 |

| Kochi | 55.2 |

| Shimizu | 42.0 |

| Omura | 33.1 |

| Chiba | 41.0 |

| Ichinomiya | 56.3 |

| Nara | 69.3 |

| Tsu | 69.3 |

| Kuwana | 75.0 |

| Toyohashi | 61.9 |

| Numazu | 42.3 |

| Choshi | 44.2 |

| Kofu | 78.6 |

| Utsunomiya | 43.7 |

| Mito | 68.9 |

| Sendai | 21.9 |

| Tsuruga | 65.1 |

| Nagaoka | 64.9 |

| Hitachi | 72.0 |

| Kumagaya | 55.1 |

| Hamamatsu | 60.3 |

| Maebashi | 64.2 |

Related posts:

Views: 1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 29th, 2021

October 29th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: