A week ago, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy spoke to the Belgian parliament. Because of the interests of the European diamond industry, he said, the European Union has refrained thus far from imposing restrictions on the import of diamonds from Russia. “We’re fighting a tyranny that wants to dismantle Europe and to eliminate those who sanctify freedom… But there are people to whom Russian rough diamonds [diamonds in their natural state], which are sometimes sold in Antwerp too, are more important,” he said during a videoconference from besieged Kyiv.

The United States and Great Britain have blocked the importing of diamonds from Russia, and the EU is considering the matter. In Israel, which in normal days takes up about 10 percent of the rough diamonds Russia exports, there isn’t even any public discussion of the possibility.

In practice, a small number of Israeli diamond dealers, licensed importers of Russian merchandise, continued to import rough diamonds from Alrosa, which is owned by the Russian government, at least until mid-March. Since that time they have been encountering obstacles, mainly banks that are balking at transferring payments to Russia. There is no impediment in law that would stop them from continuing to trade with the Russians, incidentally (indirectly) injecting money into Russia’s war.

The diamond industry is not an outlier. In effect, Israel has not imposed any sanctions on President Vladimir Putin, the businesses supporting his government, or oligarchs close to him. But when it comes to diamonds, Israel’s neutrality is likely to be of unique significance, potentially affecting the efficacy of the U.S. sanctions. A loophole in the U.S. law could turn Israel, or the Israeli traders, into a channel for bypassing the sanctions, and for bringing diamonds originating in Russia to the United States, legally.

Owned by the Kremlin

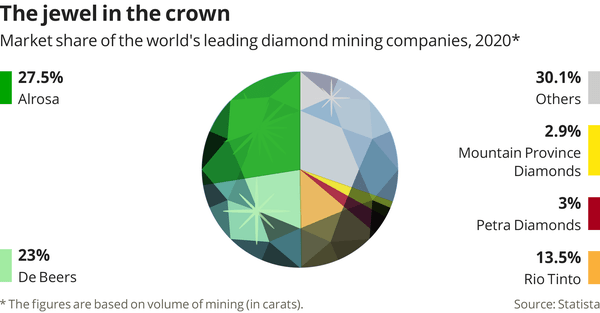

Alrosa is considered a monopoly in diamond exports from Russia, and is the world’s largest supplier of rough diamonds. According to U.S. Treasury figures, when it imposed the first sanctions against Alrosa in February (some further sanctions were imposed this weekend) , the company was responsible for about 90 percent of diamond exports from Russia and about 28 percent of the world’s rough diamond market.

Alrosa itself, incidentally, claims on its website that it controls 99 percent of the exports of Russian rough diamonds. Its main competitor is the global De Beers syndicate, which controls about 23 percent of the global market.

As is the norm for companies exporting key goods from Russia, Alrosa is effectively controlled by the Kremlin. About a third of its shares are held by the Russian Federal Government. Another third is owned by the Sakha-Yakutia Republic (part of the Russian Federation), an area in the Russian Far East that is remote, frozen, and rich in diamonds. The rest of the shares are held by employees and private shareholders and are traded on the Russian stock exchange.

The strong man in Alrosa since 2017 is CEO Sergei Sergeyevich Ivanov, who was appointed the head of the national mining company at the age of 37. Ivanov is the son of Serge Borisovich Ivanov, who is considered one of Putin’s close confidants. Ivanov Sr. is Putin’s special adviser on environment and transportation and sits on the Russian Security Council. He formerly served as Russia’s defense minister, deputy prime minister and chief of staff in the president’s bureau. The two Ivanovs, father and son, have appeared on the U.S. list of sanctions as of late February, along with Alrosa.

‘Diamond dealers, certainly anyone who has become a sightholder, are no suckers. They find a way to pay. If not from Israel, then from an account in Dubai’

Alrosa’s sales totaled about $4.2 billion last year, the company stated. Of that $4 billion stemmed from selling rough diamonds, and the rest comes from polished diamonds. It netted about $1 billion in 2021.

As in the case of De Beers, Alrosa itself does not sell on the retail market or on the global diamond exchanges, but through a limited list of several dozen regular customers, “sightholders,” as they’re called in the diamond industry, a name actually coined by De Beers, but which is also used among diamantaires for Alrosa’s franchisers. These sightholders are guaranteed a regular annual supply of rough diamonds worth tens of millions of dollars, and sometimes even more. They may polish the stones and sell them, or sell rough diamonds. Sometimes a diamond will pass via several intermediaries before reaching the end of the value chain: a piece of jewelry.

Five Israeli sightholders

On the eve of the imposition of the first sanctions against Alrosa, the company’s website named 51 “special customers” and “members of the Alrosa Alliance,” in other words the company’s sightholders for 2022 to 2024. The list was removed after the sanctions were imposed, but it can easily be reconstructed, and it named five Israeli sightholders: A. Dalumi Diamonds, owned by diamond dealers Meir Dalumi and Rafi Yerushalmi; Sahar Atid, owned by diamond dealer Yair Sahar, who served as the president of the Israel Diamond Exchange from 2011 to 2013; Leo Schachter Diamonds, one of the largest Israeli companies, owned by businessman Elliot Tannenbaum; and Niru Diamonds, owned by Ranjeet Barmecha, an Indian diamond dealer who settled in Israel a few decades ago, and is considered a prominent player on the diamond exchange. Closing out the list is Y. Dvash Diamonds, owned by diamond dealer Yoram Dvash, who was president of the exchange until late 2020 and was given Alrosa sightholder status during his stint as president, when visiting Russia on business. He even met with Alrosa CEO Ivanov.

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, diamonds imports from Russia to Israel totaled $413 million in 2021, accounting for about 60 percent of Russian imports to Israel. Most of this amount is apparently divided among the five abovementioned sightholders. Ergo, exports to Israel represent about 10 percent of Alrosa’s global activity.

That sounds like a lot, considering the size of the Israeli economy and of the country itself. In effect this figure actually attests to the continuing decline of the Ramat Gan Diamond Exchange, once a world center of trade in rough and polished diamonds, which has been slowly but surely losing status to India, which has become a diamond polishing hub. Another rising player is the United Arab Emirates, Israel’s new ally, which offers diamond dealers a lenient tax policy and a permissive banking system when it comes to enforcing the rules against money laundering, an issue that is still considered an advantage in the diamond industry.

The most important destination for the export of Russian diamonds to Europe is Antwerp, Belgium, where the diamond industry is flourishing, and where Jews – some of whom are Israeli citizens – play an important role. Some companies operate both in Antwerp and Ramat Gan, such as Taché Diamonds, another Alrosa sightholder, which also has representatives in the Israel Diamond Exchange in Ramat Gan.

In recent weeks the foreign media has publicized reports of a lobby activated by diamond dealers from Antwerp to prevent the inclusion of the import of rough diamonds on the list of EU sanctions. So far, their efforts seem to have worked. The EU – as opposed to the United States and Great Britain – has yet to place Alrosa or Russian diamonds on the list of sanctions. That is the backdrop for Zelenskyy’s speech to the Belgian parliament.

One person battling to scale down Israel’s trade with Russia following the invasion of Ukraine is attorney and human rights activist Eitay Mack. apparently with little chance of success. Writing to the Economy Ministry’s supervisor of diamonds in late March, Mack urged that licenses given to Israeli diamond dealers who trade with Russia be revoked.

Israeli law does in fact grant the supervisor of diamonds the power to grant and revoke licenses, subject to Israel’s foreign policy. But as long as the policy is that Israel is not joining the sanctions against the Kremlin, the supervisor, Ophir Gore, has no legal means to prevent trade with Russia. In his reply to Mack, Gore recited the hollow declaration by Foreign Minister Yair Lapid that “Israel will not become a bypass route for the sanctions imposed on Russia,” without any explanation of why it shouldn’t do so, as long as Israel itself is not adopting sanctions.

According to a source familiar with diamond data, from the start of the war to mid-March, Russian rough diamonds continued to enter Israel without hindrance. But about three weeks after the start of the fighting the U.S. sanctions list was expanded, and since then banks, and transport and insurance companies that deal with the diamond industry, have been making things difficult for Alrosa sightholders, which has led in effect to a cessation of imports. This may be only temporary.

Israeli banks turn touchy

If the international sanctions regime persists over the long term, Alrosa could become a significant source of oxygen for Moscow. The Israeli diamond industry has the potential to contribute its part, because the loophole in the U.S. law allows bringing diamonds originating in the Alrosa mines into the U.S. jewelry market, as long as they pass through Israel en route.

The U.S. imposed sanctions against Alrosa and against the import of Russian diamonds in general, and although it is considered the most important market for ornamental diamonds (as opposed to industrial diamonds, such as those used in discs for cutting concrete or in dental equipment). The loophole involves polishing the gems in a third country. U.S. tax law defines that third player as the country of origin, as long as the stone underwent “a significant transformation.” So a Russian stone polished in Israel can be shipped to the U.S. as an Israeli product.

Although some of the Israeli sightholders whisper to colleagues that it would be “convenient for them” to stop dealing with Russian merchandise until things blow over, they could theoretically find a way to bypass the obstacles raised by the banks. Note that the Israeli banking system is not subject to the American or European sanctions regime against the Russians. It subjects itself to rules that are more stringent that the law demands, probably in the aftermath of the moneylaundering affairs involving banks Hapoalim, Leumi and Discount, which cost the banks’ shareholders fines amounting to billions of shekels.

A leading diamond dealer active on the Israeli-Russian axis says the Israeli banks won’t touch payment to Russia now, even if it’s legal, “even if I transfer to someone in Dubai and he transfers it to the Russians. That’s their risk management policy.”

How is Alrosa reacting to the cessation of trade? Aren’t they threatening to cancel the sightholders’ franchise?

“I can attest that meanwhile the Russians understand what’s happening. Nor are they disconnected. Alrosa has an office here in the diamond exchange, the people who work there are young, educated, they understand the Western world and the sightholders’ problem. If you ask me, they themselves don’t identify much with their crazy president’s war. Take into account that Israel is only a small part of Alrosa’s business, and as far as I hear, trade in India and Dubai is continuing as usual, so that they aren’t getting stuck with all the merchandise. Meanwhile there’s no pressure on the sightholders to continue to buy.”

Another industry source thinks that in fact, even assuming the Israeli diamond dealers find ways to resolve the matter of payments, delivery and insurance, the Israeli sightholders will likely move their activity to India: “In any case polishing in India is cheaper than in Israel, and there’s a flow of Russian merchandise, without any problem or restriction. Someone like Elliot Tannenbaum has no problem receiving the goods in India, and sending them from there to the United States. As long as there are Western sanctions, there’s no reason for them to pass via Israel.” Tannenbaum’s Attorney Amir Altshuler, it should be noted, claims his client stopped his dealings with Alrosa or any other Russian company completely after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Others are dubious that Israeli trade with the Russians in general has halted, or significantly diminished, because of payment difficulties. “Don’t believe a diamond dealer who tells you that a bank restriction stopped him,” one source said. “Diamond dealers, certainly anyone who has become a sightholder, are no suckers. They find a way to pay. If not from Israel, then from an account in Dubai, if not today, then with a guarantee to pay when the sanctions are lifted. The fact is that I don’t see any lack of Russian merchandise in the market.”

Blood diamonds and barefaced lies

The diamond industry never did have a gorgeous image, partly because of the so-called “blood diamonds” mined in countries suffering from hunger, bloody conflicts and corruption, such as Angola during the long civil war in the late 20th century.

One method to thwart trade in “blood diamonds” is the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, named after Kimberley, South Africa and formulated in 2003. It formulated standards for the diamond trade that were ultimately adopted by United Nations institutions and most of the major countries involved in the diamond trade. It basically involves a process of registering and documenting the history of rough diamonds.

Every rough diamond exported or imported in the member countries is supposed to have a document attesting to its origin (where mined), its history, weight and qualities. The document certifies that the stone was purchased from a legitimate mine, with a legal license. It’s supposed to stop the diamond industry from financing bloodthirsty militias, child labor, and other ills. Along with the certificate there is registration in the Kimberley international system, which is designed to prevent the development of a forged documents industry.

In recent weeks several major jewelry makers, including Tiffany, Pandora and Cartier, have vowed to stop buying diamonds mined in Russia

“One of Kimberley’s shortcomings is that it defines conflict diamonds only as those that finance a non-governmental military organization. That’s a definition that was designed to catch rebel organizations rather than governments. Therefore, no matter what the Russian army does, there’s no way of declaring the Alrosa diamonds conflict diamonds or blood diamonds,” explains Edahn Golan, a veteran diamond industry analyst. “The second problem is that decisions in Kimberley are made unanimously by representatives of the member countries – in other words, Russia has a right to veto the decisions. Therefore the Kimberley Process can’t harm Alrosa in any way.”

The Kimberley Process could help simply by identifying diamonds as Russian. In recent weeks several major jewelry makers, including Tiffany, Pandora and Cartier, have vowed to stop buying diamonds mined in Russia, in light of the war crimes being committed by the Russian army in Ukraine.

Presumably, the fashion chains can enforce the declarations by examining the Kimberley certificates of the diamonds they purchase, but customarily, from the moment the diamond is polished, it is exported without its certificate – in other words, jewelry manufacturers don’t examine the Kimberley certificates prior to acquisition. So how can the jewelry companies know where the diamonds were mined?

A diamond dealer who owns several mines in Africa claims that the fashion chains are satisfied with a declaration from the traders who sell them the merchandise: “Make no mistake. These declarations by the chains are nothing more than public relations. No jewelry company has any idea where the diamonds were mined. I can take a Russian diamond and say it’s from Botswana. The only thing they have is my word for it.”

“Tiffany, as opposed to the other chains that issued declarations, is also a direct customer of Alrosa [through one of Tiffany’s subsidiaries] and is included on the official customer list,” notes Nurit Rothman, a veteran diamond dealer and a former director of the Diamond Producers Association. “When you read Tiffany’s announcement, you see that they aren’t ending the trade, they’re postponing it. It’s cautious wording, designed to prevent them from getting into trouble with a major supplier. I assume that within a few weeks they’ll resume buying diamonds from Alrosa. They have no interest in losing the contract.”

As opposed to fears in the diamond industry, the U.S. and British moves against Alrosa did not substantially jack up diamond prices. Actually since the war began, prices of polished diamonds have slightly dipped.

Golan suspects the explanation lies more in COVID-19 and less in Ukraine, partly because weddings were being postponed as the pandemic began. “Later, there was an overall increase in personal consumption, which was also reflected in the demand for diamonds. Recently this trend has changed, and at the moment it seems that the jewelry chains have accumulated inventories, while there has been some decline in demand,” he says. It is also possible, though difficult to calculate, that loopholes in the sanctions regime are affecting the business as well.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 14th, 2022

April 14th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: