Researchers studying the fossilized hands of 2-million-year-old hominins have concluded that human thumbs back then had the same movement ranges as our thumbs have today. It was the “dexterity” in part offered by the human thumb that enabled us to overpower all other species on Earth.

Until now, the ancient origins of the human thumb, and dexterity, have always been tightly locked archaeological mysteries. By 3D modelling the muscle movement range in ancient, fossilized thumbs, a team of German researchers has concluded that it was about 2 million years ago that our early human ancient ancestors first developed this key survival tool.

The Human Thumb: All The Better To Squeeze With!

The new study was published in the journal Current Biology by a team of paleoanthropologists from the University of Tübingen. The researchers digitized ancient hominin fossil thumb bones, including those of Homo sapiens (us), in a project riddled with complications.

The main problem facing the research team was the fact that fossils don’t preserve muscles and that meant relying on the risky approach known as “speculation.”

To help them accurately analyze ancient human thumbs the team of researchers first looked at hand bone samples from two early modern humans and four Neanderthals who had all lived and died during the last 100,000 years.

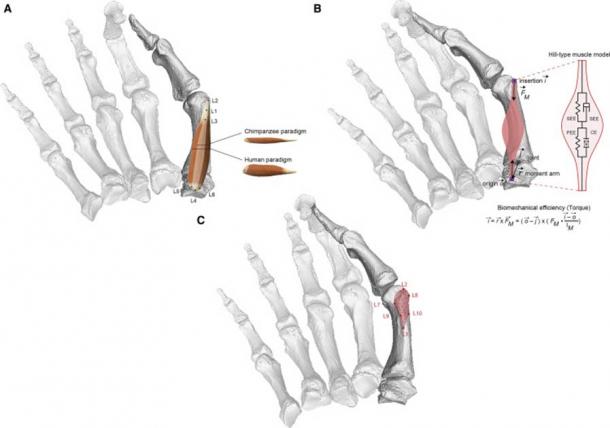

Summary of the study’s analytical steps: (A) Model preparation and assumption of either human or chimpanzee muscle force-generating capacity (m. opponens pollicis). (B) Biomechanical efficiency is calculated as the torque generated by m. opponens pollicis at the thumb’s TMC joint. (C) 3D geometric morphometric analysis of proportional bone projection across the metacarpal muscle attachment site. (© 2021 Harvati, Karakostis and Haeufle / Current Biology )

An article in Science Mag says the German scientists then analyzed the hands of “the diminutive, cave-dwelling H. naledi who lived from about 250,000 to 300,000 years ago,” and also those of a sister genus, “ Australopithecines.”

Using 3D technology, the researchers reconstructed the ancient hands and then “digitally” added a key muscle known as the “ opponens pollicis ” which is attached to the base of the palm and allows the thumb to flex inward.

The right hand of Australopithecus sediba. (Image by Peter Schmid, courtesy Lee R. Berger and the University of the Witwatersrand./ CC BY-SA 3.0 )

How The Human Thumb Became The Power Tool Of Evolution

Having built their dynamic 3D models of ancient hands, the researchers applied increasing force to the model. It was observed that with more applied force “better, more precise grips” were achieved.

This, according to the authors, would have helped in “holding steady a needle and thread or swinging a hammer.” In conclusion, the scientists said all of the tested members of our genus, Homo, had “basically the same thumb grip strength,” and that this matches the strength measured in the thumbs of modern humans and chimpanzees.

During their experimentation, the team looked at the thumb movements in two hominin specimens discovered at the Swartkrans site in South Africa. Dating to about 2 million years ago, and from an unknown genus, the authors said these Swartkrans’ fossils represent “the earliest known humanlike thumbs in the fossil record.”

The study notes that in comparison with these two Swartkrans fossils “ Australopithecines had much weaker thumbs.” And while they may have exhibited tool-related behaviors they had not yet developed a humanlike level of efficiency, according to the authors.

What this means is that the human thumb as it is today evolved about 2 million years ago in the Homo genus, and that it was the thumb that accelerated ancient humans’ ability to make more complicated stone tools and weapons , which in turn helped us surpass all the other hominin groups.

This ancient human is giving us the “thumbs up” for good reason because the latest study shows that the human thumb is what separates Homo sapiens from the cousins we left behind as we evolved to “uber-humans.” ( Zemler / Adobe Stock)

An Excellent Research Project But Questions Remain . . .

Dr Tracy Kivell, a professor at the University of Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conservation in the UK, told CNN that a lot of “assumptions” are made in these types of studies because “muscles are not preserved in the fossil record.” But accepting that a degree of speculation was involved in the research, she said the authors of the new paper “did an excellent job of dealing with all of the complexities involved in this kind of research.”

However, there is another voice that urges “caution” towards the conclusions of the new study for another reason. Dr Evie Vereecke is an anthropologist and anatomist at Belgium’s KU Leuven University, and while she openly praises the authors’ “approach,” she told Science Mag the findings should be treated with caution. She said, “We [evolutionary scientists] know that ‘dexterity’ is not only due to one muscle.”

Put another way, dexterity has a massive mental component that was not accounted for in the 3D-modelling of the German research team. Therefore, it is still not known how “capable” humans were applying their “super-thumbs” in projects that required complex foresight and the prediction of outcomes.

The full study is available with open access from Elsevier, Current Biology, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.041

Top image: Researchers used 3D modeling software to reconstruct ancient hands and then added the critical human thumb muscle to the model. Source: © 2021 Harvati, Karakostis and Haeufle / Current Biology

By Ashley Cowie

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 30th, 2021

January 30th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: