Why Is the Ruling Establishment Simply Incapable of Responding Any Other Way to the Pandemic?

On the morning of 27th April I got a phone call from the youngest son of a trade union veteran of Kanpur, that everyone in his large household has been down with COVID-19 (henceforth Covid)-like symptoms. Though the condition of others was stable, his father’s oxygen levels were going down, and they had not been able to find either oxygen, or more importantly, a bed for him in any hospital. I called up the coordinator of a community help group being run for the Covid-affected in my academic campus. He reminded me that his father-in-law, who used to stay with him, had passed away on that very date a year back. That year-old story was repeating itself, of course in a much more grotesque form, with no oxygen, no hospital admission, and a sense of complete loss and helplessness. In the interim a whole long year has passed, when instead of looking at cricket scores we have become used to looking at Covid numbers the first thing in the morning.

What we are seeing, even in the alternative media, is primarily about those who have any sort of access (or think that it is their right to have access) to the ‘system’, in terms of testing, doctor’s attention, medicine, oxygen, ambulance, beds, so on and so forth. The actual reality is far grimmer when we look at those who never enjoyed that access. The neighbouring locality of Nankari, with a population of around 50,000, is separated from our elite and idyllic college campus by just a high security wall. In Nankari – where all those who serve us, from our household workers to contract workers of all kinds, those cleaning, manning security, running the mess, stay in their thousands – there is not access to a single ‘qualified’ doctor. There are only jholawala doctors.

Friends tell that these days there are queues of hundreds, all with similar symptoms, before the doors of these jholawala doctors. In fact some of them have closed their practice, as they are not able to access even regular medicines, and yet people are reaching out to them in hordes at their homes; since the jholawalas live in the same locality anyway, they cannot abandon their patients. As one old associate, who also stays in Nankari, observed about the present health crisis, “only these jholawalas have saved the country”!

In Nankari it is not as if there has been a sudden exodus of qualified doctors. With all its population and its mix of working class and middle class residents, for the 27 years that I have lived in the campus, to the best of my knowledge there never was any access to a qualified practitioner for most of the working classes. Even for the relatively better off there was no qualified practitioner in the locality itself. Only when there was a severe crisis would they consider going to one of the many nursing homes on GT Road and neighbouring commercial localities. So in the present circumstances, there is no testing, and of course mostly no further follow up on Covid, beyond the symptomatic treatment by these jholachaps.

Thus, as those of us who try to keep an ear to the ground are very aware, it is not as if there is a sudden medical crisis due to Covid. For the common folk, any medical contingency has always been a great and almost insurmountable crisis. Only now the crisis has also reached those who thought that they had the right contacts and enough in their pockets to take care of themselves and their dear ones.

In December last year, amid the pandemic, my father suffered a stroke in Allahabad (now renamed ‘Prayagraj’). While doing countless trips between the hospital and home, at every crossing we could hear the loudspeaker blaring that we ought to strengthen the hands of our revered Chief Minister Yogi by following all the Covid guidelines — staying indoors, wearing masks, etc. — and thereby defeating the virus. On one such crossing, one chilly morning, a beggar woman approached our rickshaw at a red light and asked us what we were doing with all those masks and so on. “Do you people have any shame and how do you think that people like us are managing on the streets?”

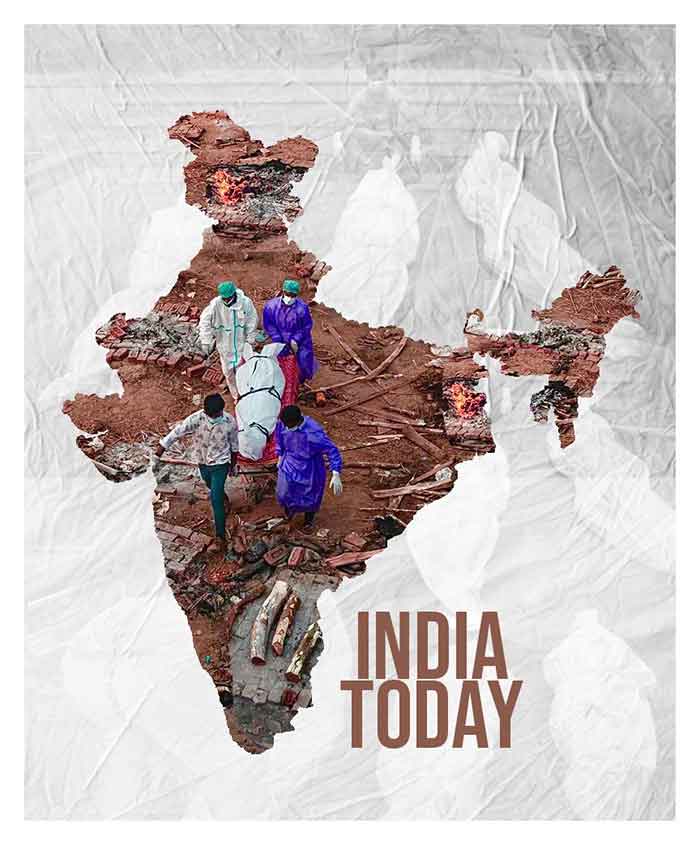

Thus it would be simplistic to think that this problem is of one year’s making. Indeed the deep fissure due to the pandemic demonstrates what really is required: community health workers (trained and properly paid, unlike what we have done with the present Asha workers) to monitor the health in communities and localities, regular preventive health measures, a well functioning and well equipped hierarchy of public health centres beginning from primary in the residential localities to the secondary and tertiary health facilities, connected right from the rural to the large urban centres. But we are painfully aware as we turn to May 2021, as the pandemic seems to be singeing or burning literally every household across the country, this perfectly achievable goal sounds like a far-fetched utopia.

Many have rued the fact that a whole long year has been lost. Had there been better ‘planning’ for the pandemic (tests, medicines, oxygen, beds, even personnel, etc.), we would not be in the abyss we are in. But my simple submission is that the present regime is basically not programmed to think and work in any systemic and strategic manner when it comes to the welfare of the common people, pandemic or no pandemic. Yes, of course it can strategise and plan, and even operationalise its plans, but those plans must concern something grandiose that fits in with their conception of the nation they think they are in the process of building – a majestic Ram temple at the ‘janam bhumi’, where none other than the former principal advisor to the Prime Minister has been given charge of making the temple into a grand reality before the next elections; or a spectacular new central vista in the nation’s capital so that history remembers the new rulers (thus, even amidst the pandemic, construction of the central vista has been declared an ‘essential’ service). Even if the plan concerns health, it must take the form of imposing pronouncements about how many countries India is supplying the vaccine to, and hence what a great nation we are, and the like; forget the fact that Covishield, which India is producing, has been developed by researchers at Oxford University. Also the fact that for so many critical raw materials involved in production of the vaccines we are dependent primarily on the US and Europe, and a moratorium by those nations on exports can bring even such licensed production to a grinding halt.

In spite of all the noise about ‘make in India’ and ‘atmanirbhar bharat’, and all the grandstanding of our technical prowess, we can hardly make a thing by ourselves. Perhaps the pharma industry is a partial exception, one that is being flaunted so much by our leaders. But two important points are relevant here. One, to the extent there is any indigenous pharma industry in India, it is thanks to the concerted battle in early post-independence India (some of it even before independence) to chart an independent path, with an indigenous network of public research labs and public sector units to make bulk drugs and nurture indigenous capabilities. Most importantly, a path-breaking Patent Act of the 1970s opened up possibilities for the indigenous pharma industry to develop and thrive and for India to become the ‘pharmacy of the world’. But, within a generation, all that has been systematically eroded with the signing on the dotted lines of the new global IP regime under WTO by the Congress government in the 1990s. What we have been left with is a rump of an indigenous pharma industry, pathetically dependent on international forces. For instance, the Indian pharma industry is dependent on China for 70 per cent of its needs of active pharma ingredients (API, mostly for antibiotics and vitamins) at present. Amid the rise in Covid cases now, a great worry for the pharma industry is, if China stops regular freight services to India, how would those needs be fulfilled?

One of the ideological tenets of the present establishment is that it need not really involve itself directly in the welfare of the common folk; such ‘detailing’ ought to be left to the so-called market forces. Correspondingly, the only impediment for ‘economic development’ is the lack of free play for private capital. Witness, first, the dismantling of labour rights by the passage of ‘labour codes’ during the lockdown, and then the three farm laws to unleash the ‘animal spirits’ of markets in agriculture. It does not matter what farmers want or what workers think of these codes, they are all petulant juveniles who do not know what is good for them. The other impediment for such rapid development, according to the establishment, is the historic State presence in various strategic sectors of the economy, and hence the great impatience to do away with the ‘problem’ once for all through asset selling, divestment, privatisation, etc. For all this unleashing of ‘animal spirits’, the pandemic is an opportunity.

So to expect from this regime that it make not only monetary investments but carry out painstaking institution-building in health is simply wishful thinking. That is amply borne out by the past year’s experience. We should also remember that there is a great consensus across the parliamentary political spectrum that things like education and health should be best left to private initiative, mostly the corporate sector. Amid the pandemic, even a state government that wants to sound benevolent would at best talk about health insurance. The moot point is, how would insurance help in getting an oxygen cylinder? But no one is willing to ask that question. It is a great irony that Dr. Manmohan Singh goes to the very public All India Institute of Medical Sciences for Covid treatment. Perhaps that is what we will be left with – such privileged islands of public systems to which certain well-connected sections go, while the remaining, rich and poor, are to be ‘treated’ by the market forces – the former in seven-star corporate hospitals, the latter on the street.

Market forces are indeed in charge right now, with everything being auctioned to the highest bidder, from medicine to oxygen to cremation spaces. This market utopia is not the folly of an individual or two but the consequence of what the local and global elite have systematically tried to build in this subcontinent in the past three decades. It is only now, with the fire lit by the pandemic, we can see the reality in all its starkness.

As far as the State is concerned it has only one job with regard to the common people – to discipline them to become good subjects of the market. When they complain too much, apply the National Security Act on them, as the UP government has been doing when they complain about oxygen, or for that matter anything else – CAA, farm laws, it does not really matter. Meanwhile Mr. Adar Poonawala, the CEO of the Serum Institute, has moved to his newly rented £50,000-a-week London mansion. And as Covid cases in India soar daily to new peaks, Mr. Mukesh Ambani has bought the historic Stoke Park estate, close to London, for US$79 million at April-end this year. Stoke Park, a shooting site for two James Bond films, has one of the finest golf courses in England, and tennis courts for Wimbledon players to practice on.

Given that this is our rulers’ vision of development, one should not be surprised at where we find ourselves.

Rahul Varman teaches at IIT Kanpur (rahulv[at]iitk.ac.in)

Originally published in RUPE India

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX

Related posts:

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 12th, 2021

May 12th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: