Some artifacts, even when they were discovered a long time ago are hard to authenticate and some certainly are fakes. The Hercules Sarcophagus is one such artifact, widely regarded to be a hoax. This object was discovered in Tarragona, Spain, during the 19 th century. It was used as evidence for the Egyptian colonization of the site, and gained acceptance amongst Spanish nationalists of that period, as this piece of “evidence” matched traditional Spanish narratives. Outside of Spain, however, critics were extremely skeptical about the authenticity of the Hercules Sarcophagus, and dismissed it as a hoax.

About 60 years later, however, the Hercules Sarcophagus entered the spotlight once more, this time linking the city to the Phoenicians. The proposerof this link was able to make this argument partly because he did not know that the fragment he was looking at actually came from a fake artifact. Had he known the true origins of the artifact, he might have considered carefully whether to take it seriously or not. Clearly, there is an interesting story that surrounds the Hercules Sarcophagus – with some surprises.

There are several examples in existence of the Hercules Sarcophagus that are not fake. This one from the Palazzo Altemps, Rome, shown from the side, depicts some of The 12 Labors of Hercules. ( © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro )

The Discovery Of The Hercules Sarcophagus of Tarragona

On the 9 th of March, 1850, a marble sarcophagus was discovered by workers quarrying stone for a harbor project at Tarragona, a city on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in northeastern Spain. The sarcophagus had strange inscriptions and carvings on it, but the workers did not notice them until it was too late. As a consequence, the artifact was broken into pieces. Fragments of the sarcophagus, however, were salvaged and studied by a local antiquarian, Don Buenaventura Hernández y Sanahuja.

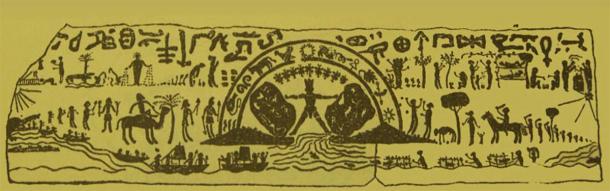

A drawing of a large fragment from one side of the fake Hercules Sarcophagus, showing Hercules in the middle, which has been used by various scholars in their claims and explanations. ( Archaeology.org)

In the center of a large fragment of the sarcophagus is the figure of Hercules in the process of creating the Strait of Gibraltar. This comes from the myth of the Twelve Labors of Hercules , specifically, the hero’s 10th labor in which he is commanded by Eurystheus to bring the cattle of Geryon to him. In order to accomplish this task, Hercules had to travel to the island of Erythia, at the western end of the world. During this journey, the hero travelled across Libya, and arrived at the point where Africa meets Europe. According to one version of the myth, Hercules commemorated this feat by splitting a mountain into two. The new mountains became known as the Gates or Pillars of Hercules, whilst the area between them became the Strait of Gibraltar.

On the fragment of the Hercules Sarcophagus, there is an arch with a zodiac over the figure of Hercules. More importantly, however, are the figures to the left and to the right of the hero, especially the former, where a crocodile, a palm tree, and a procession of people can be identified. These people have been interpreted as representing ancient Egyptian colonists, whereas those on the right of Hercules, are viewed as the ancient inhabitants of Iberia.

Some classical authors wrote that Hercules had led an army into Iberia, died there, and was buried in Gades, now known as Cádiz. These ancient authors also identified Hercules with the Phoenician / Punic god Melqart, and even went so far as to refer to the god as the “Egyptian Hercules.”

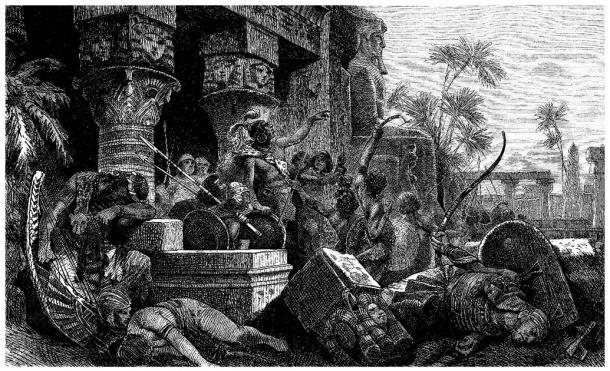

The Hyksos invaders in ancient Egypt, who were eventually pushed out of Egypt into Iberia but chased by the Egyptians. (Erica Guilane-Nachez / Adobe Stock )

The Hercules Sarcophagus of Tarragona Used For History

Although Hernández y Sanahuja’s interpretation of the image makes no reference to Hercules bringing an army into Spain, he does retain the notion that there was a connection between ancient Egypt and ancient Iberia. According to the antiquarian, the Hyksos, who had established the fifteenth dynasty of Egypt, fled westwards after they were expelled by the Egyptians. They eventually arrived in Iberia, and constructed Tarragona’s early walls.

The Egyptians, however, were in pursuit of the Hyksos, and when they arrived in Iberia, they formed an alliance with the indigenous population against their sworn enemies. In the end, the Hyksos were defeated, and the victorious Egyptians settled down in Spain. Hernández y Sanahuja went on to assert that the sarcophagus was made for the Egyptian leader who brought the colonists to Spain, or one of his descendants.

Despite the fantastical nature of Hernández y Sanahuja’s claims about the Hercules Sarcophagus, they were readily accepted by Spanish nationalists of that time, as his narrative agreed with that Spanish tradition. By associating themselves with the ancient Egyptians and armed with the “evidence” of the Hercules Sarcophagus, the nationalists were able to boast of the antiquity of their nation.

The cartoon-like drawing of what was supposed to be carved in the fake Hercules Sarcophagus ( Archaeology.org)

Scholars outside Spain, on the other hand, were quick to dismiss the artifact as a hoax. They pointed out, for instance, that the carvings on the sarcophagus are quite cartoon like. This is most visible in a fragment with an “ elephant-headed god .” This deity is depicted wearing a kilt and holding a mummy in its trunk. The god is standing in a boat, with an owl behind him. Curiously, Hernández y Sanahuja’s publication of the sarcophagus also included an ushabti (a small funerary figurine), which seems to be authentic.

It is a tantalizing idea that Hernández y Sanahuja may have fabricated this fake artifact and added a real ushabti to make it seem more realistic. The truth, however, might be hard to find, as the antiquarian was bent on get rid of his Resumen Historico-Critico de la Cuidad de Tarragona . He destroyed every copy he could get his hands on. Consequently, this is now an extremely rare manuscript.

The Roman Hercules Sarcophagi that is now part of the Uffizi Gallery collection in Florence, Italy. ( Uffizi Gallery )

In 1916, The Hercules Sarcophagus of Tarragona “Reappears”

Nevertheless, this has not stopped other scholars from taking the alleged hoax seriously. In 1916, almost 60 years after the Hercules Sarcophagus was discovered, the artifact caught the attention of the scholarly community once again, when Arthur Frothingham, an American art historian and archaeologist, published an article in the American Journal of Archaeology about a fragment of the Hercules Sarcophagus.

In his article, Frothingham argued that the carvings on this particular fragment were an example of Phoenician iconography, thereby demonstrating a connection between the Spanish city and this ancient culture. By referring to the fragment as the “Phoenician Tablet of Tarragona,” Frothingham showed that he was aware of where the artifact was from. Nevertheless, he seems to not have had sufficient knowledge of the object’s exact origins. After all, Frothingham was of the opinion that the fragment came from a circular artifact, and not a fake sarcophagus.

In any case, the sarcophagus was soon denounced as a fake again. Pierre Paris, a French art historian and archaeologist, dismissed the Hercules Sarcophagus as “une enfantine parodie” (“a childish parody”) in a commentary in the Revue archéologique in 1921.

Lastly, it may be noted that whilst this particular Hercules Sarcophagus was most likely a fake, real Hercules Sarcophagi have been found by archaeologists in the past. One of these, for instance, was found in the town of Genzano di Roma, and now resides in the British Museum, whilst another, believed to be from Rome, is today displayed in Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Both the sarcophagi have been dated to the Roman period, and on their exteriors, a number of the Twelve Labors of Hercules are depicted, hence the name given to these artifacts. Needless to say, these relief carvings are of a much higher quality than the ones found on Hernández y Sanahuja’s fake Hercules Sarcophagus.

Top image: There are several examples in existence of the Hercules Sarcophagus that are not fake. This one is kept in Kayseri Archaeological Museum, Turkey. Source: CC BY-SA 2.0

By Wu Mingren

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 10th, 2020

November 10th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: