Renegade Editor’s Note: This article was written in 1976. Things have only gotten worse since then.

It is precisely because the final goal of architecture is universality that it first must be rooted in time and place. Only in transcending these limitations does it become great. Regionalism is a qualifying discipline which insures a sense of quality. Universality unrelated to regional roots is all too obnoxiously obvious; and ultimately commonplace. This rootlessness is the vacuous sophistication so characteristic of our big cities.

Regionalism is a creative ingredient in architecture. It makes for an intimacy that prevents architecture and all art — from lapsing into formality or formula. Architectural diversity depends upon the consideration of the diverse factors of regions: past history, temperament, ideals, habits, climates, raw materials, geography, and such an old-fashioned item as individuality.

According to our modern architects, regionalism has been made obsolete by technological progress. Philip Johnson and H. R. Hitchcock, Jr. have stated:

The architect has a right to distinguish functions which are major and general from those which are minor and local. In sociological building he ought certainly to stress the universal at the expense of the particular. He may even, ‘for economic reasons and for the sake of general architectural style, disregard entirely the peculiarities of local tradition unless these are soundly based on local weather conditions. His aim is to approach an ideal standard.

This “ideal,” boiled down to its essence, is the ignoring of historic tradition and the theoretic grafting upon society of utopian ideas. Inevitably, the problems of “sociological architecture,” while they leave us politically free, engender cultural collectivism.

This pragmatic-liberal ideology is dominant among our “intellectuals,” who have given themselves the task of rebuilding our cities in the next forty years. For instance, the Kennedy family has recently selected the “internationalist” architect I.M. Pei to do the Kennedy Library. On the other hand, the Guggenheim Museum in New York caused a great debate just because it didn’t “conform” to the homogeneous city-scape of the utopians.

Modern Architecture

With few exceptions for individual sparks of talent, expressed largely in a formal sort of lyricism, modern architecture has become afflicted with rectilinear rigor mortis, the chief difference between architects being that one clique specializes in “rechopped” rectilinear and the other in “channeled” rectilinear. The differences between Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building, Gordon Burnshaft’s Lever House and Eero Saarinen’s CBS Building, all in New York City, are solely in the proportion of rectilinear shapes.

It is claimed that technology has made this uniformity not only necessary, but desirable — a deterministic fallacy that is an abdication of man’s role as a creative agent. Instead of shaping his architecture himself, man must have his architecture shaped for him by a machine. What has been lost sight of here is the difference between a work of art made with a machine and a work of art being a machine.

Due to its emphasis upon structure, modern architecture is supposedly, to use Sorokin’s terms, a revolt against sensate nineteenth century culture, and a return to the more structural architecture of the ideational Romanesque and idealistic Gothic. The truth is, it is sensate culture incarnate. In the world-renowned Bauhaus of Walter Gropius, the artistic effect depends not only upon the huge surfaces of glass, but upon their reflection onto and into each other. Reality has been reduced to surfaces and the surfaces have been multiplied. The same holds true for so much of the rest of our grey flannel functionalism. The bare fact soon becomes barren of any spiritual value.

Older architectures were of organic, not mechanistic form, and were symbolic of a supersensory realm of values. When present-day architects build churches — on somewhat rare occasions — they all too often come out looking as if they were factories designed by atheists, i.e., Mies’s I.T.T. Chapel and Le Corbusler’s Ronchamp (the latter with the pathetic apology of the architect that it represents “twentieth century man’s attempt to believe”). Eero Saarinen is a little more forthright when he classifies his church architecture as “almost religious.”

Mies’s architecture has rightly been associated with “the climate of Plato.” But the notion of independent existence is an anachronism that has been criticized by Alfred North Whitehead. The idea of completeness in itself within its own independent frame destroys the sense of mystery. For Instance, Mies’s Seagram Building is a work of architecture which is complete, independent of its surroundings and accordingly stripped naked to the bone. The contrast with Gothic architecture is obvious. Every Gothic cathedral is not only international but distinctly regional. Equally important, Gothic “incompleteness” imparts a sense of mystery.

Another factor differentiating modern from Gothic architecture is the former’s theoretical perfection, a debt to Renaissance rationalism. The shift of interest from the Gothic to the Renaissance style was really a shift from symbolic to theoretical perfection. Modern architecture’s demand for mechanical exactness (which exactness Whitehead has characterized as “fake”) is proof, once again that it is not a step towards ideational culture but an anachronism of sensate culture.

Our Wasteland

The problem of the ugliness of industrial society is related to the disintegration of sensate culture. It is a matter of concrete feeling having become divorced from abstract knowledge. No abstract reading of the “great books” is likely to raise our architectonic standards. Indeed, in the United States we have the situation in which one of the most literate countries in the world is rapidly becoming the ugliest.

Perhaps the most disturbing thing about our current cultural explosion is that it has no architectonic character. A painting here or a sculpture there may have some beauty. But the country at large has been left to sow its seeds of ugliness. Without architecture art serves as the fig leaf of an ugly age.

There will never be the required cultural synthesis as long as egalitarian liberalism is the reigning social philosophy. The whole notion of hierarchical ordering is foreign to it. The demand for constant change is anathema to the social urge to build great architecture. Architecture is synonymous with permanence. Consequently, a deracinated society cannot build creative architecture. The contrast between Gothic and Renaissance architecture illustrates this. The Gothic ages were rooted in a transcendental conception of reality, which created an architecture unprecedented in our Western tradition. The Renaissance was an era obsessed with time, as ours is, and accordingly it built a time-bound eclectic architecture.

The hierarchical ordering of the Middle Ages was permeated with religion, so that even matter was suffused with immateriality. It was just because there was no separation between spirituality and down-to-earth life that an everyday art like architecture was felt to be the most important art.

When in the Renaissance hierarchical ordering was abandoned, man became an end in himself. In overvaluing himself, he devalued the world. Matter and Mind were no longer organically interrelated (recall Descartes). When we assume “the bare valuelessness of mere matter,” it becomes possible and even necessary to exploit nature. In becoming “mere matter” the world ceases to have any intrinsic esthetic importance. Art becomes a frivolity and architecture ceases to inspire. As proved by the French Revolution with its defacing and destruction of Gothic architecture, the subjectivist culture must seek to destroy the architectonic culture.

American Architecture

Lewis Mumford, in “Sticks and Stones,” has shown that one of the last acts of a dying Medieval Europe was to plant a seed in the New World that eventually became the American Architecture of Jefferson; Henry Hobson Richardson, the “shingle style” and neo-Romanesque; Louis Sullivan and the Chicago School; and Frank Lloyd Wright and organic architecture. Rooted in regionalism, a sympathetic attitude for nature and a respect for individuality, this architecture was the first art to master the machine and put it to human use. If modern architecture is any indication, it may also prove to have been the last.

The ineffable mysterious quality of their work has caused it to be written off as “romantic escapism.” But, the mystery of art is what makes it perennially interesting. The advocates of dehumanized art are the real escapists. This quality of mystery was infused in the work of Sullivan and Wright by complex geometrical forms. It is best seen in Sullivan’s ornament which was “of the surface, not on it.” Wright made use of it in his floor planes, and his work has often been called horizontal or prairie Gothic. In Europe, besides a few art nouveau architects such as Mackintosh and Van de Velde, this form quality is best seen in the work of medievalist Antonio Gaudi. When in his old age Louis Sullivan was asked his opinion of Gaudi’s Cathedral in Barcelona, his reply was that it was one of the highest flights of the creative spirit of our time. There can be little doubt that in Europe as in America a mechanistic social system has chosen to ignore its organic architecture.

It is not enough to say, with New York architect Edward Durrell Stone, that our present scorched earth policy makes us want to commit suicide. No less than a complete break with the prevailing ideology is needed. But first an overall view of society is required. No social philosophy that makes change for the sake of change its cardinal tenet is likely to preserve the past for the sake of preserving it.

A society doesn’t acquire culture after it has become affluent. Art is not a luxury item, but the very essence of life, a spiritual efflorescence that is an “unbought grace.” The richer we become, the uglier we become. No amount of mere money spent on “the public domain,” as Professor John K. Galbraith desires, will cure the problem of social taste. It will make it worse by deluding people into thinking that our automated architectonics, divorced from spiritual values, is in itself progress — a progress that is the opium of our so-called “intellectuals” and one that distracts attention from whatever cultural synthesis we already have.

Mass Destruction

American architecture has both been ignored and destroyed. The death toll of Wright’s and Sullivan’s great buildings is too long to recite. Over half of Sullivan’s buildings have been either razed to the ground or altered beyond recognition. Wright’s buildings have fared better, but Japan is getting ready to tear down his epochal “meeting of the East and West,” the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. Owing to the fad that there are no longer any rich people in Chicago with enough taste to acquire either Wright’s Oak Park Studio or his Avery Coonley House and keep them intact, these buildings are being “progressively” ruined. Two years ago Sullivan’s Babson Residence (Chicago) was destroyed along with his swan song, the Garrick Theater (Chicago), to make way for a parking ramp. This year his Dooley Block In Salt Lake City will be demolished. His finest essay in small residences, the Albert Sullivan house in South Chicago is almost certainly doomed. And there is the sad case of the greatest American house ever built: the Robie House owned by the “progressive” University of Chicago and now being allowed to turn into a shambles.

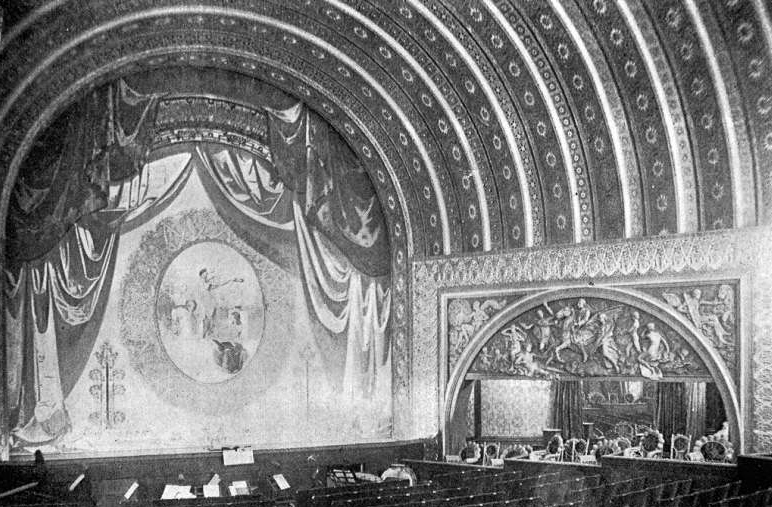

All this with hardly a note of protest. But what else could be expected when modern architecture is solidly controlled by the intellectual devotees of an “international style?” The American Institute of Architects has protested the destruction of Penn Station In New York City (a building that owed its design to the “international style” that swept the country after the Columbian Exposition of 1893, and destroyed the grass roots of the Chicago School), but didn’t raise a peep about the destruction of the Garrick Theater. At the very moment we were hearing a lot of gibberish about a “flowering of the arts,” one of the world’s great buildings was destroyed to make way for a parking ramp. To understand the banality of the destruction of the Garrick Theater it is necessary to try — hard as it may be — to imagine Venice destroying the Doges Palace to make way for a horse stable, and a mere seventy years after its erection. It is worth noting that the Garrick Theater was done away with by a judge reversing lower court rulings protecting it and that Arthur Goldberg, then a member of President Kennedy’s cabinet, chose to defend the right of a wrecking company to destroy it.

Our country is an artistic wasteland relieved by a few works of architectural achievement that are rapidly disappearing. In the end the ugly egalitarian “boxes on the hillside” will be all that are left.

If there is an organic unity between culture and society, the treatment of our Indigenous architecture portends political calamity. It is well to consider the fact that National Socialist Germany, anti-Semitic though it was, left standing the greatest Jewish architectural achievement to date: Eric Mendelssohn’s Einstein Tower. Communist Russia, anti-religious though it is, has carefully preserved its church architecture. Yet in the United States a mindless, tasteless bureaucratic capitalism is indiscriminately destroying our greatest social art.

Source: Instauration magazine, October 1976

Source Article from http://www.renegadetribune.com/death-american-architecture/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 27th, 2017

October 27th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: