Unlike the author of this academic biography who never met the Palestinian leader Tawfiq Zayyad and only knew of him through the mainly Zionist Hebrew press, I knew Tawfiq Zayyad and respected him since the Nakba. At that life-changing juncture, he was nearly twice my age of eleven years, someone with literary promise, revolutionary bend of mind, daring, Palestinian nationalism, communist convictions and a booming voice to back it all up in his speeches. Yet this rising star was approachable even to me and my agemates. His harsh-edged voice was difficult to ignore especially with the-then-recent addition of loudspeakers.

In 1954, despite the iron fist of the Military Government that Israel had imposed on us, its Palestinian citizens, my eighth-grade classmates in Arrabeh, my home village in Galilee, led by my communist cousin, Tawfiq Kanaaneh, launched a remarkable and successful strike to protest the Head Tax that was levied from us but not from our Jewish majority co-citizens. Despite the years-long military government’s revenge against the families of its pupil leaders, the strike spread to other Arab schools and led to the abolition of that apartheid tax.

Recently, reminiscing with my cousin Tawfiq, he mentioned another successful strike from that era, one I had completely forgotten, possibly because it was limited to local peasants in Galilee. Traditionally, in early winter, agricultural laborers from our less-landed households had sought employment as olive pickers in the fields of more-landed farmers, often in other Galilee villages. With the Nakba’s ethnic cleansing of over 500 Palestinian communities from the region that became Israel to refugee camps in neighboring Arab countries, the Israeli military government officials granted contracts to tend many abandoned productive olive groves to favored local bosses and collaborators. Contrary to the standard traditional practice of daily payment of hired agricultural laborers with a standard measure of the produce they had picked, those contractors started to delay payment till the end of the season when they would decide, retroactively, how much to pay their hired help. Communists in Arrabeh, including my cousin, led a successful strike here as well. This significant victory had somehow faded from the public’s memory. Doubtless, Tawfiq Zayyad inspired this one as well.

Arrabeh celebrated its Head Tax victory with mass meetings at which Tawfiq Zayyad, the rising communist star and Palestinian nationalist, exercised his crowd charm and booming voice. Here is how Israeli journalist Y. Kinarot reported this event that launched Abu el-Amin (‘The Trustworthy One’ was always how we, his contemporaries and friends, interpreted his Nom de Guerre to mean) as our lead resistance poet and politician. The excerpt is from Ma’ariv in June 1957, and it was sarcastically titled, “Nasser Didn’t Come to Tawfiq Zayyad’s Aid”:

Ignoring the Military Government’s rules that ban entrance to closed areas [Read: all Arab residential communities in Israel] without permit from the security authorities [Read: Military Government officials who usually didn’t grant it], Zayyad used to “hop” freely [Read: get smuggled, often using agricultural backroads] from one Arab village to another, gathering peasants in the village square, and delivering fiery hate speeches [Read: fiery condemnation of the apartheid Head Tax] against the government, the authorities, and the Military Government until the security forces ambushed him and in one of his last “dashes” in 1955 arrested him in ‘Arraba, the notorious Arab village [Read; the typical Palestinian village that dared to object] in the central Galilee. In the middle of his speech they loaded him into the police prison-car and took him to the nearby police station.

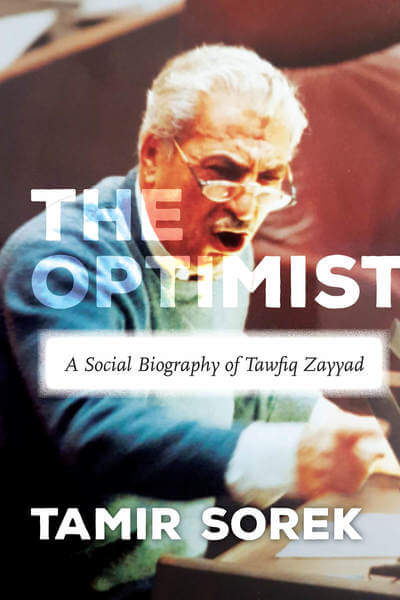

Tamir Sorek, the author of “The Optimist: A Social Biography of Tawfiq Zayyad” (Stanford University Press, Kindle Edition, 2020) notes that Zayyad’s famous visit to Arrabeh took place on April 24, 1954, when he celebrated the release of four political activists in the village from jail. Zayyad called for a tax revolt and a student strike, and was arrested and confined to house arrest from sundown to dawn, and barred from leaving Nazareth for six months. From that arrest until Zayyad became a member of the Knesset in 1974, Sorek notes, the military government and the police frequently restricted his freedom of movement.

In his introduction, Sorek, accuses Israeli “orientalist scholars” of working for the Israeli security services officially or otherwise. He exempts himself from this taint with the statement, “There is no easy way around this dilemma, so I warn readers that this book cannot pretend to be more than what it actually is: an empathic presentation of an iconic Palestinian political and cultural figure by a Jewish Israeli scholar.”

With that, he leaves begging for an answer the glaring question of where he stands on Zionism? None of his learned associates that I contacted seems certain of his formal stand on that one. Hence, I have to fall back on his allowed “Jewish Israeli” identity. With that in mind, It would be insulting to the scholar if I were to assume that he is unaware of the shortcomings of the negative conception in the standard “Jewish Israeli” press of Palestinians in general and of their leaders in particular. To illustrate such biases, I have added in the above quote, in brackets, my ‘translation’ of some of the phrases that the original reporter had used. My conclusion on this point should be obvious: I don’t think Tamir Sorek intentionally derides Tawfiq Zayyad. Rather, he doesn’t distrust the standard biased “Jewish Israeli” sources that he draws on to put the final touches to his subject’s portrait. Sorek correctly argues with the journalist who reported the above piece about the likely date of the event. But, he lets stand all the underhanded innuendoes with no objection or comment.

What moves the “Jewish Israeli” public media and officials to such standard bias, one may ask? That is the mother of all questions in our case. Our mere continued existence was, and still is, unplanned and undesirable in the eyes of the average Jewish Israeli. At issue was, and still is, our attachment to the traditional source of our livelihood, our agricultural land that had always been part and parcel of our identity and source of pride. In the eyes of our majority co-citizens, that whole ball of wax was and still is an inborn defect in our claim to citizenship, equality and human rights in Israel.

In the 1970s, after I returned from the United States to Arrabeh, my home village, as its first medical doctor, the booming voice on the loudspeaker of Zahi Khateeb, Arrabeh’s young ironsmith who announced most local Communist Party events, had a mystical cheerful effect on me. Now I think I know why I was cheered whenever I heard Zahi’s announcements, often without understanding their content: It must have been the magic influence of Abu-el-Amin’s voice on me. Arrabeh was where he first made his leadership big splash with the resulting arrest as reported in the above quote which the author lets stand with little objection, comment or explanation. Later, we read of Zayyad’s account of the repeated torture sessions by the police in the city of Tiberias. Zayyad described being strung up by his arms and legs to the window frame of his cell and beaten till he lost consciousness. Zayyad called his torture a “crucifixion,” similar to the ways British Mandate authorities tortured Palestinian rebels in the uprising of 1936-39. Every time he woke up he would spit in the face of his torturers and they would beat him unconscious again. No wonder his family reports that he had a lifelong physical aversion to visiting Tiberias.

Despite the crucifixion, Zayyad’s secular bend didn’t encourage the occasional hint from friends at comparison with his fellow Nazarene, Jesus Christ. Yet the author dwells at length on the religious analogy between his subject’s commitment to Communism and the religious belief and dogma of Moslems. I sense this is an innocent interpretation of our hero’s reality. However, it is open enough to suspicion. I can imagine Zayyad’s friends arguing that this is a damning low blow; it accuses him of being one with his worse political enemies, members of the Islamic Movement, in practicing blind worship with the only difference being the identity of the deity, Marx vs. Allah.

The story of Zayyad’s illegal dashes from one Galilee village to another is from the book’s second chapter titled “Steadfastness”. Zayyad’s legendary physical and moral defiance best characterizes this single most characteristic descriptive word in the English language for our community’s struggle– we the Palestinians, whether citizens of Israel, residents of the Occupied Palestinian Territories or members of the Palestinian Diaspora. For the uninitiated, I add: with our daily struggle and suffering, whether individuals as Abu el-Amin, or in communities as Nazareth and Arrabeh, we have defined a unique brand of this standard weapon of the weak common to all indigenous and downtrodden minorities in the world; we have popularized it worldwide as “Sumoud”. Add to this general theme the unique gifts of Abu-el-Amin as one of its practitioners, whether in jail, at public rallies, or in the Israeli Parliament. To our minds, Abu el-Amin’s name was enough to highlight our optimism and trust in his and our principled stand against injustice and in defense of our rights, his Sumoud with his legendary literary flare and optimistic belief in the ultimate victory of the struggle of the working classes, his loud protest of injustice and his unerring stand against the rising fascism on the Israeli right embodied at the Israeli parliament by the likes of Rahba’am Ze’evi. Sumoud was and still is our expression of our hope for a better and more just future and Abu el-Amin was its flesh and blood symbol.

Zayyad’s communist “utopian vision” combined with his poetic gift, his great sense of humor and his native full familiarity with his audience’s temperament, propelled him to become “the first communist city mayor in the Middle East and a long-time member of the Israeli Knesset.” He never displayed evidence of fear or hesitated to speak his mind forcefully, often ridiculing his opponents to the cheers of his supporters. On such occasions, I remember being not only convinced of his nationalism and peace advocacy, even though I was never invested in his deep communist vision and principles, but also thoroughly entertained.

Back to my quoted paragraph: As I read this first and only English-language academic biography of the hero we all admired, I contacted several of the people the author referenced as his sources of information. Without exception, they all praised his thoroughness and persistence in seeking first-hand info. At some level, he exceeded their expectations with repeated quotes from oral testimonies of former allies of Zayyad who no longer subscribe to Communism. Yet, the author never contacted any of the living and fully cogent half dozen participants in organizing the event in “ ‘Arraba, the notorious Arab village in the central Galilee”. Could he have been dissuaded by the village’s notoriety, I wonder?

Even if we are to accept his distancing himself from the standard Israeli orientalists’ practice of service to the Shin Bet, Tamir Sorek does not question the standard maligning discourse regarding Zayyad’s struggle against the Apartheid military rule at the time and lets stand with no objection, not even any hint of a light-hearted dismissive qualifier, the standard Zionist media dumping on his subject, Tawfiq Zayyad, with his “hate speech” and his “notorious” host village of ‘Arraba’, my ‘Arrabeh’. To me, this hidden landmine of discrediting Tawfiq Zayyad’s political and literary inspirational status by keeping silent vis-a’-vis his detractors is unacceptable.

Again: to people like me who were there at the time, the issue at hand was stark and simple: The Zionists targeted our sole source of livelihood, our agricultural land. I probably wouldn’t have noticed the underhandedness as all that damaging if I had received a clear admission from the author of his Zionist bend of mind, an attitude and even a character qualifier in the eyes of Palestinian readers of my age. Such open suspicion by me and my agemates is mostly lacking toward the inoffensive identifiers of “Jewish” and “Israeli”, though the latter has always implied certain enmity to us, especially with the ongoing occupation of all of historical Palestine since 1967.

Another example of Sorek’s unquestioning acceptance of standard Israeli media lure is his seeming exoneration of David Ben-Gurion on the issue of near ethnic cleansing of Nazareth in 1948. Jonathan Cook had already debunked such claims of innocence. Yet Sorek keeps to the Zionist tribal narrative of innocence crediting the prime minister’s decision to his political savvy in view of Nazareth’s importance to the world’s Christian community. Hidden in the folds of such narrative is the fact that Ben-Gurion had already issued his oral order to evacuate all of the city’s residents. Only when the Canadian Jewish commander of the invading Hagana force, Ben Dunkelman, demanded a written order did Ben-Gurion shelf his former evacuation decision. Instead, he seems to have started already planning an alternative strategy to demographically and administratively overpower Nazareth. In the 1950s, he proceeded to create on its confiscated lands and on the lands of its neighboring Palestinian villages the modern city and administrative hub of Upper Nazareth, now renamed Nof Hagalil.

Here is one more example of the author’s unquestioning of standard Israeli sources and of my questioning of same: Sorek reports casually Zayyad’s participation in a mission of several hundred laborers from Nazareth to assist in orange picking in Jaffa. Conflict was reported between those guest laborers and the Palestinian internal refugees who had gathered in Jaffa. The reason is reported to be the Nazareth men’s alcohol drinking. Careful readers who check the notes would discover that the source of this possible rumor was the office of the Minister of Minority Affairs, the parallel central structure to the Military Rule created to oppress and pilfer us, the remaining Palestinians in Israel. Tamir Sorek is not unaware of the malicious potential of such standard Israeli sources. Yet, he seems to appreciate their derisions as “entertaining and colorful caricatures of Zayyad” and to pass them uncritically, even appreciatively:

[An Israeli] author (and former deputy for the adviser on Arab affairs for the prime minister) Uri Standel gave [Zayyad] the colorful title, “the venomous poet,” and poet Haim Guri referred to him as “an unbearable mixture of Jesus, Stalin, and Arafat.” The journalist Yehushu’a Bitsur added, “His eyes sparkle with the fire of hate.”

Then Sorek gives a lukewarm defense of his subject:

This collective fear of Zayyad reflected deep-seated Zionist anxieties, unrelated to Zayyad’s words and actions. At the same time, Zayyad elicited these anxious reactions more than any other member of his party. This fear of Zayyad is puzzling, given that he consistently presented himself as a citizen of a state who demanded reform and as a leader of a national minority who demanded rights within the framework of citizenship—

By this stage, I seem to be as undecided about the stand of the author of this biography, Tamir Sorek, as he is about his subject, Tawfiq Zayyad. What did I expect from him, anyhow, I ask myself? To his credit, Sorek gives an excellent example of what is expected from an impartial admiring researcher, though he himself falls short of such eample. He writes:

“The journalist David Halevi met with [Tawfiq Zayyad] for several long meetings and produced the most detailed and nuanced journalistic profile of Zayyad ever written [in Monitin in 1981]…. Monitin’s editor, Adam Baruch, had a clear agenda of challenging the existing image of Zayyad among Israeli Jews. He added his own paragraph to the interview [satirizing] the common Jewish Israeli perception of Zayyad: … Baruch’s text would remain a valid parody of the Hebrew media’s representation of Zayyad for years to come, … [Later] more journalists discovered the gap between Zayyad’s stereotypical caricature and his actual personality and political worldview.”

With his gradual rise in the party, Zayyad utilized his Nazareth base, including the city council, as a power base, firing off messages to Arafat and to the Israeli Knesset. His hopes for IsraeIi-Palestinian peace together with Yitzhak Rabin’s readiness to reward the Palestinian minority in Israel with specific community projects led the two to collaborate despite their past differences. Currently, Ayman Odeh, the lead Arab politician in Israel, is emulating Zayyad’s cautious steps in weighing supporting a Zionist party from outside its expected ruling coalition.

This level of politicking, according to Zayyad himself, kept him busy enough that he had no time for writing poetry. However, Sorek offers an alternative and less flattering explanation averring that Zayyad spoke differently to different audiences, and the Knesset had the wrong audience for his poetry.

This is the familiar two-faced tactic, especially familiar among our intellectual class, we the Palestinian citizens of Israel, and most especially among a sizable group of our graduates in the social sciences from the University of Haifa with its contortionist and remolding artist professors such as Sami Smooha and Arnon Sofer. Such assessment is a low blow to our hero, Zayyad, especially with his lead position among Palestinian resistance poets. With such examples in mind, the author’s innocent-sounding analysis acquires a damaging edge. And so does his claim that Zayyad’s poetic contribution was a mere tool in the service of his political ambitions.

At the risk of damaging my own case, let me assert my readiness to accept the explanation that Tamir Sorek had good intentions in choosing to write a biography of Tawfiq Zayyad. For that I am personally thankful to him. Where he falls short is in ridding himself of the “Jewish Israeli” tribal prejudices and inimical presumptions about all things Palestinian.

The least he could have done was to visit Arrabeh and assess firsthand how “notorious” it actually is. Very likely, he would have realized that, nowadays, Arrabeh is famous for having the highest rate of physicians per population of any community in Israel, Arab or Jewish. Some fellow Arrabeh residents blame me for starting the trend. I, in turn, blame Abu el-Amin and his fellow Communist Party leaders for the many full scholarships they arranged for local communist youth to study at the universities of the Soviet Union before its demise.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 20th, 2020

December 20th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: