Many scholars have suspected that the monuments of Stonehenge were carefully arranged to function as some type of calendar. Proof of this concept has been hard to come by, however, as even the most informed Stonehenge experts have labored to comprehend how long-lost culture utilized this mysterious structure. In an article just published in the Antiquity Publications Ltd , archaeologist Timothy Darvill from Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom disclosed what he believes is the most likely solution to the enigma: the Stonehenge solar calendar.

“The numerology of these sarsen [large standing stone] elements materializes a perpetual [Stonehenge solar] calendar based on a tropical solar year of 365.25 days,” Professor Darvill wrote in his paper.

He acknowledges that ancients in northwestern Europe could have developed such a calendar on their own. But he is intrigued by the possibility that they imported the Stonehenge solar calendar concept from somewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean region, like Egypt, where solar calendars were most certainly used in ancient times. The new research introduces new thinking and also shows that the Stonehenge solar calendar concept was likely imported from the Middle East or north Africa.

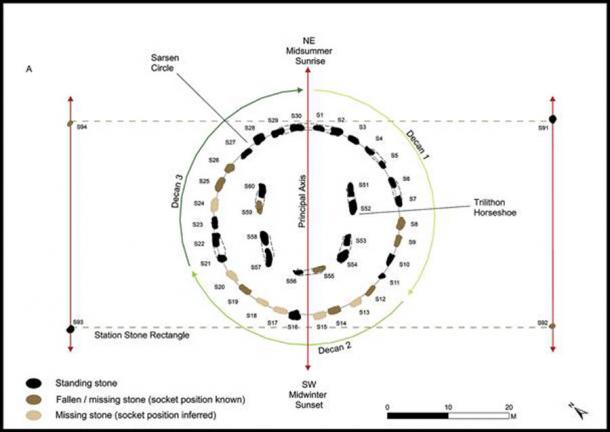

How the numerology of the sarsen elements create the perpetual Stonehenge solar calendar. Non-sarsen elements have been omitted for clarity. (V. Constant / Antiquity Publications Ltd ).

The Fascinating Stonehenge Solar Calendar Thesis

Professor Darvill’s solar calendar thesis is based on a careful reconstruction of Stonehenge’s construction phases, and on the apparent evolution of its design and structure.

Construction work began at Stonehenge in approximately 3,000 BC. Notably, the stone sarsens that Darvill believes form a calendar were all quarried (from the same location) and erected at about the same time, between the years 2,620 and 2,480 BC. This suggests the monumental site was used for another reason originally, before being converted into a solar calendar by a sun-worshipping culture that occupied the Wiltshire region, where Stonehenge is located, in the mid-third century BC.

Stonehenge in its current form consists of three distinct sections. The largest and most prominent of these is the Sarsen Circle, which several thousand years ago would have consisted of 30 tall standing stones arranged in a circle. The majority of these are still standing today, although seven have fallen and six were removed from the site by thieves or scavengers at some point.

Bridges were formed by heavy rock lintels that were placed on top of the standing stones. However, only a few of these connecting lintels are still in place, the rest have either fallen off or are missing.

There are wider-than-usual gaps between some of the stones, which act to separate the 30 stones into three distinct subsets of 10. The first stones in the second and third sets are smaller than the other 30 stones in the circle, which reinforces the notion that some type of division was intended.

The second section at Stonehenge includes five huge monuments known as the Trilithons. These were placed inside the Sarsen Circle, arranged in a horseshoe shape that curves from the southwest at the bottom to the northeast at the top. The largest of the stones is the one that directly faces the southwestern sky, while the smallest are those that are aligned to face northeast.

The Stonehenge Trilithons were placed inside the Sarsen Circle, arranged in a horseshoe shape that curves from the southwest at the bottom to the northeast at the top. ( Public domain )

The third group of stones includes four much smaller sarsens, which were placed at four points around the Sarsen Circle to form a 260-foot by 100-foot (80-meter by 30-meter) rectangle. This formation is known as the Station Stone Rectangle. Only two of these stones is still in place, but it is always possible to establish where standing stones once stood at Stonehenge because of the empty sockets that can be found in the ground.

Significantly, the Stonehenge site is bisected (divided in half) by a straight axis that is oriented from southwest to northeast. This means that all the standing stones are divided into two equal sections that mirror each other on either side of the axis. On its two ends the axis points to the exact spots in the sky where the sun sets on the winter solstice sun and rises on the summer solstice, linking together the two most important milestones of the solar year.

For Darvill, all the information a person needs to decode the true meaning of Stonehenge is found in these alignments and arrangements.

The orientation of the site’s central axis puts the two solstices front-and-center, as would be expected in any solar calendar. Under Darvill’s scheme the 30-stone circle represents the 30-day month, which has been conveniently divided into three 10-day weeks for the sake of convenience.

Passing around the circle 12 times would take the observer nearly to the end of the solar year (360 days), leaving just five extra days to be accounted for—which they are, by the five Trilithon stones that stand inside the circle, curving from southwest to northeast.

The four smaller stones of the Station Stone Rectangle would help complete the calendar’s cycle, representing an extra quarter-day each (remember, a tropical year equals 365.25 days). Four stones of one-quarter day each would equal one full day when added together, and that of course is what would need to be added to the calendar every fourth year (every leap year) to preserve the calendar’s accuracy over the long term.

All of this is very neat, symmetrical, and tidy, and requires no imaginative leaps or eccentric interpretations of the facts to make its case. Darvill’s hypothesis is evidence-based, and it will require an evidence-based counterargument if it is to be refuted.

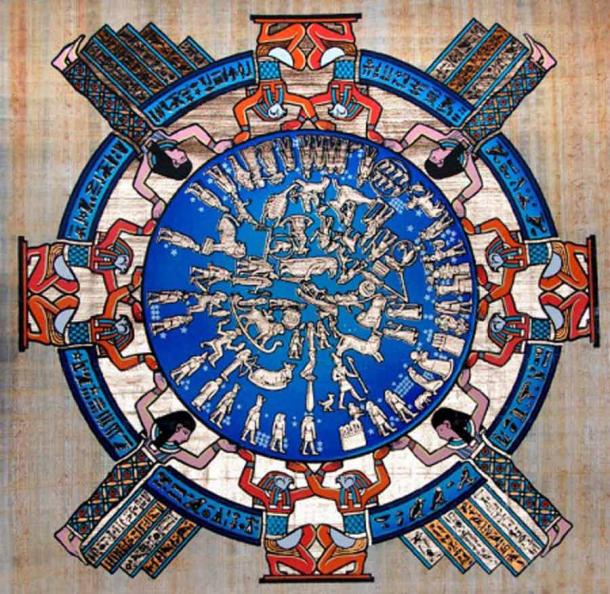

The Egyptian solar calendar from 3000 BC, pictured here, was circular and even resembles the aerial outlines of Stonehenge. The ancient Egyptian calendar made farming and growing crops easier and was in wide use until it was replaced by Ptolemaic calendar in 232 BC ( Egypt online blog )

Stonehenge Roots Found in Ancient Egypt?

The builders of Stonehenge left behind no documents behind that clearly spelled out their intentions. But Darvill points out that other cultures of the time were unquestionably using solar calendars.

“Such a solar calendar was developed in the eastern Mediterranean in the centuries after 3000 BC and was adopted in Egypt as the Civil Calendar around 2700 and was widely used at the start of the Old Kingdom about 2600 BC,” Darvill explained, in a Bournemouth University press release discussing his research.

If Darvill’s theory about Stonehenge is correct, some type of intercultural exchange that influenced the evolution of religious practices and beliefs in ancient Britain may have taken place. A solar-based metaphysical system may have been imported from distant shores, partially or as a whole, from the Middle East, North Africa, or another area in the greater region.

Not much is known about the types of contacts that may have occurred between such cultures four or five thousand years ago. But future archaeological discoveries and ancient DNA analyses could turn up evidence that shows extensive interactions did in fact occur.

In the meantime, Professor Darvill is delighted by the opportunity to contribute to the discussion of the true purpose of Stonehenge, one of the most famous and speculated-about ancient sites found anywhere in the world.

“Finding a solar calendar represented in the architecture of Stonehenge opens up a whole new way of seeing the monument as a place for the living,” he said. It can be imagined as “a place where the timing of ceremonies and festivals was connected to the very fabric of the universe and celestial movements in the heavens.”

Top image: A new research study has “proven” the Stonehenge solar calendar theory, and reveals that the solar calendar concept was likely “imported” from Egypt. Source: Vic / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 3rd, 2022

March 3rd, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: