St. Paul Companies Spend Tax Breaks On Super Bowl Sponsorships

Above Photo: Union Advocate

WITH MORE THAN a million people headed to the Twin Cities over the next 10 days for the Super Bowl, local corporations, St. Paul school district officials, and civic leaders are bracing for what may be a public relations nightmare: the first teachers strike in St. Paul in over 70 years.

The St. Paul Federation of Teachers, nine months into its contract negotiation, authorized a strike vote for January 31. The move comes amid the union’s unconventional strategy of linking declining school funding to corporate tax cuts and narrowing in on local companies on the Super Bowl Host Committee as a potential source of funding for the cash-strapped school system.

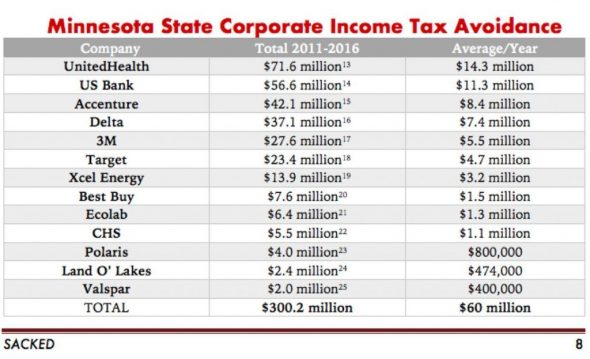

The argument the teachers are making in their contract negotiations is straightforward. Cuts, they say, are not the answer. The school district’s financial situation can never really improve until corporations start paying their fair share. In particular, teachers are focusing on the companies that make up the founding sponsors of the Super Bowl Host Committee – companies the union says have avoided paying $300 million in state income taxes over the last five years alone.

The companies say they have made up for some of that with donations, but the generosity has limits. According to a public records request filed by the teachers union, only seven of the 25 Super Bowl Host Committee founding partners donated to the St. Paul public school district last year – for a total of $1.1 million. All 25 companies, by contrast, paid $1.5 million to be founding Super Bowl partners.

Nick Faber, president of the St. Paul Federation of Teachers, stressed that the 3,700 educators in his union do not want to go strike. What they do want, he said, is to see the school district commit to supporting changes to the state tax code, under which corporations have enjoyed massive breaks in recent decades.

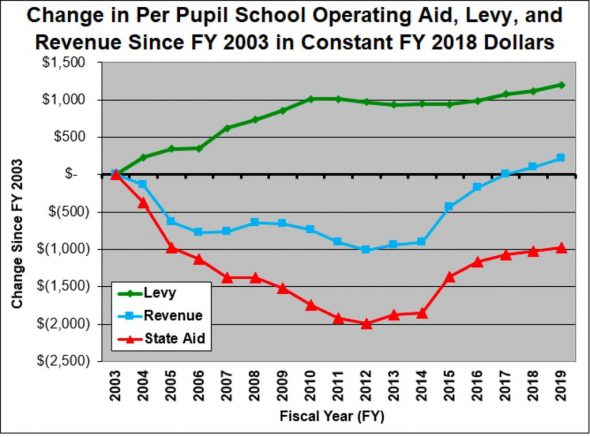

Last March, the St. Paul Public Schools announced that it faced a $27 million budget deficit, necessitating staff and program cuts to a district that had already been slashing art, music, and gym, with nurses, librarians, and social workers in short supply. It’s a familiar, vicious cycle – the state reduces its funding for public schools, which also lose revenue when students leave for charters, and districts suffer even more cuts and budget strain.

December 2017 report: SACKED: How Corporations on the Super Bowl Host Committee Left Minnesota’s Public Schools Underfunded and Under Attack. Chart: St. Paul Federation of Teachers

The wealthiest Minnesotans have seen their taxes decline over the last four decades. Back in 1977, they paid 18 percent in state income taxes. Over the next 36 years, the legislature reduced that top rate to 7.85 percent. In 2013, the state legislature bumped it back up to 9.5 percent, a move strongly opposed by the state’s influential business leader coalition. With the decline in income taxes has come a drop in real per-pupil state aid, which remains “significantly below” what districts received in 2003. While some of the major local corporations make voluntary philanthropic donations to public schools, the teachers union says those contributions have never come close to the amount the businesses have saved in reduced taxes.

Chart: North Star Policy Institute

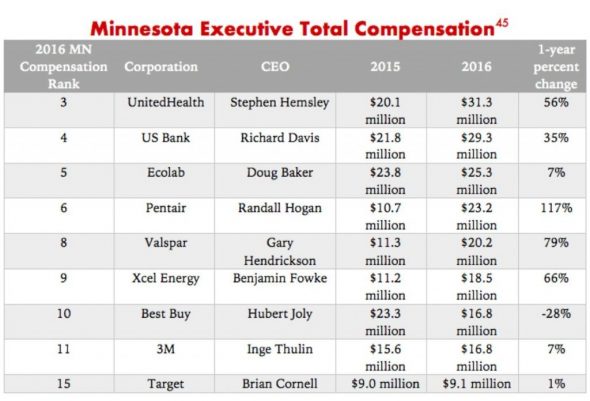

To try and shift the conversation around public education, the St. Paul Federation of Teachers has been highlighting tax havens, loopholes, corporate subsidies, and executive compensation. For example, in a report it published in December, the union noted that 3M – a technology company headquartered in St. Paul – holds $1.4 billion in offshore tax havens, including in places like Hong Kong, Panama, and Switzerland. Likewise, the union said, UnitedHealth keeps over $700 million in overseas havens like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, citing a 2017 report by the Institution on Taxation and Economic Policy.

December 2017 report: SACKED: How Corporations on the Super Bowl Host Committee Left Minnesota’s Public Schools Underfunded and Under Attack. Chart: St. Paul Federation of Teachers

Kathryn Wegner, an education studies professor at Carleton College and a parent of a student who attends Groveland Park Elementary in St. Paul, has been active in supporting the union’s efforts to highlight corporate tax avoidance. She has joined teachers for rallies outside of banks downtown and been educating other families and community groups about the fiscal situation.

“At my kid’s school, we lost the kindergarten teacher aides, then a librarian, then the music teacher, and our four kindergarten classes went down to three, bumping up class sizes,” she told The Intercept. “Parents are getting upset and wondering how to make sense of it, and understanding the historical context around corporate tax rates has been really useful to grasp the disinvestment.”

The teachers union has been asking corporate leaders to meet with them since October, and finally last week, they had the chance to sit down with representatives from EcoLab and U.S. Bank. At those meetings, the union asked for the companies’ partnership in pressuring state lawmakers to adequately support public education – specifically the state’s unfunded special education mandates.

“They said no,” said Faber. “The only way the state could really close the gaps would be to tax them more.”

U.S Bank did not return The Intercept’s request for comment.

Mesa Denny, an Ecolab spokesperson, told The Intercept that the company does not consider the situation “to be a dispute,” and it is “merely trying to correct the inaccurate and untrue information” promulgated by the teachers union.

“Ecolab believes that strong public schools are vital to a healthy community, and that’s why we have supported the St. Paul Public School System for more than 30 years,” Denny said. “Over the last five years, the Ecolab Foundation has provided more than $3.6 million to the St. Paul Public Schools, supporting strategic imperatives outlined by the school district leadership. Given that we are headquartered in St. Paul and many of our headquarters employees live in St. Paul, we are happy to devote our foundation dollars to these efforts.”

But those donations, Faber said, are not enough to bridge the school funding gap that was created in part by tax cuts. “Given how much school funding has declined, philanthropy just can’t have a real transformative change when we’re so underfunded on a basic level,” he said. “We can’t just accept little grants from corporations; we have to start thinking differently.”

The teachers want the school district to join them in pressuring local corporations to pay more. So far, they say, district officials have refused. Laurin Cathey, human resources director for St. Paul Public Schools, did not return The Intercept’s request for comment.

St. Paul teachers marched from one corporate office to another, calling on Wells Fargo, US Bank, Ecolab and Securian to pay their fair share toward fully funded public schools on December 7, 2017. Photo: Union Advocate

TO ADDRESS THE budget deficit, the school district has proposed that teachers agree to applying to “Q Comp” – a voluntary state program established in 2005 that theoretically could bring up to $9 million to St. Paul schools. But even if St. Paul did apply, the state already distributes all the money it has allocated for the program, so no money would flow to St. Paul unless the legislature decided to appropriate more money. And even if the state did bump up funding, 22 Minnesota charter schools and school districts are ahead of St. Paul in line for the money.

Tyler Livingston, acting director of school support at the Minnesota Department of Education, told The Intercept that St. Paul would not be allowed to jump ahead of the other districts waiting for money if it applied for Q Comp. “The law says explicitly that applications are treated in the order they’re received,” he said.

The union says it is not holding its breath that the state will increase Q Comp funding, especially not during an election year. “The money just isn’t there,” said Faber, “and even if it were, Minneapolis is a Q Comp district and they have a budget shortfall about the same as ours or greater, so obviously Q Comp isn’t going to really address this problem.”

In addition to corporations, the union wants to see wealthy nonprofits, like local colleges and hospitals, pay their fair share in taxes. According to St. Paul’s mayor, a third of the city’s properties are exempt from property tax.

One option is to establish a so-called Payment in Lieu of Taxes, or PILOT, program – something that exists in more than 200 cities, towns, school districts, and counties across 28 states. PILOTs are essentially initiatives to induce tax-exempt institutions to make voluntary payments to the cities in which they’re based. A civic task force formed last year to explore the idea and released a report in September, emphasizing that PILOTs “cannot – and should not – be viewed as a ‘solution’ to St. Paul’s significant budget gaps or long-term financial challenges.” A representative from Citizens League, the Twin Cities public policy group that published the report, did not return a request for comment.

“It’s really frustrating to our members that while HealthPartners” — a local health care provider and insurance company — “avoids taxes and doesn’t want to talk to us about PILOTs, they’re charging us through the roof for our health insurance,” said Faber.

The potential upcoming teachers strike would be the first since 1946, when the St. Paul Federation of Teachers went on strike for six weeks – the first organized teachers strike in U.S. history. The union also voted to strike in 1989, but ended up reaching a last-minute agreement that mooted the strike.

The St. Paul teachers union is considered among the most progressive teacher locals in the nation. Since 2013, it has joined with other progressive unions to organize under the banner of “Bargaining for the Common Good.” Inspired by the Chicago Teachers Union strike in 2012, unions like St. Paul’s have taken a different approach to their contract negotiations, partnering with local organizations to bring a wider range of community-oriented demands to the bargaining table.

Last spring, the union released a report to evaluate how much progress it had made toward reaching the goals it set for itself in 2013. While highlighting some real accomplishments — including reducing student-teacher ratios for low-income students and expanding full-day pre-K programming — the SPFT acknowledged that without more sources of revenue, it would be impossible to really tackle its agenda.

The report helped form the demands the union has since been pushing for in its contract negotiations.The union’s very first proposal is in line with its pre-Super Bowl campaign: a commitment from the school district to push major local corporations and nonprofits to increase revenue for St. Paul Public Schools and support “changes in state tax policy to make these contributions sustainable over time.”

“We’re hoping to see some movement from the school district so we don’t have to take the next step,” said Faber, meaning the strike. Faber says the district can continue to accept corporate charity, but it needs to push them to also “be better neighbors.”

That’s a very different kind of pressure, he said, “and that’s hard work, but I don’t think we have any other choice.”

Source Article from https://popularresistance.org/st-paul-companies-spend-tax-breaks-on-super-bowl-sponsorships/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 30th, 2018

January 30th, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: