When most people think about what it means to be a saint, the image that comes to mind is of a benevolent, gracious figure that exudes holiness in every cell of their being, and that every word and action they take is always in the service of a holy cause. St Guthlac of Crowland however, is an unusual saint, one who strayed from the path of righteousness to spend his youth as a knight and warrior, only to turn back to God after seeing the errors of his ways and vowing to live out the rest of his days in isolation as a hermit monk.

So how can a medieval warrior, who made a career of murder and pillaging, become a man whose reputation for holiness and ability to work miracles earned him the title of “saint”? What could possibly inspire a man to turn his back on the world in favor of a life of loneliness and hardship? Perhaps St Guthlac’s choice may not seem so strange to those of us who have felt the weight of worldly cares sitting heavily on our shoulders and wished for escape. His story can be a reminder that even those of us who seem to have it all may still in fact be missing something within ourselves, something that cannot be found in earthly things.

Stained glass panel depicting St Guthlac of Crowland, in Crowland Abbey. ( Public domain )

A Man of Future Glory is Born

Guthlac was born in the year 673, son of the nobleman Penwald of Mercia. He was descended from an ancient royal line known as the Iclings or the House of Icel. The house was named after Icel, the great-grandson of the legendary Offa, king of the Angles, mentioned in several epic poems, including Beowulf (not to be confused with King Offa of Mercia, who reigned from 757 to his death in 796). St Guthlac’s name when translated into Latin becomes “Belli munus,” meaning “reward of war,” so it seems the young nobleman was always destined for the life of a warrior.

The birth of Penwald’s son was heralded by the manifestation of signs from heaven, according to the East-Anglian monk, Felix, who wrote Guthlac’s biography:

“Lo! men saw a hand of the fairest red hue coming from heaven; and it held a golden rood, and was manifested to many men, and it leaned forward before the door of the house wherein the child was born.”

Much like at the birth of Jesus, men came from all around to witness this miracle, and when at last the child was born, a woman emerged from the house to speak to the men gathered there: “Be firm and of good heart, for a man of future glory is born here on this earth.”

Divine portents aside, the son of a nobleman and inheritor of such a powerful bloodline would have been expected to do great things in his life. In the medieval period, it was believed that lineage and ancestry determined a man’s character, and the virtues that made a good warrior were hereditary. If a boy’s father or grandfather was known to be an able and courageous warrior, then so should he be as well. Failure to display proper military values and behavior was thought to indicate an inherently flawed character and tainted bloodline, or in the case of one born from good lineage, it may call his parentage into question.

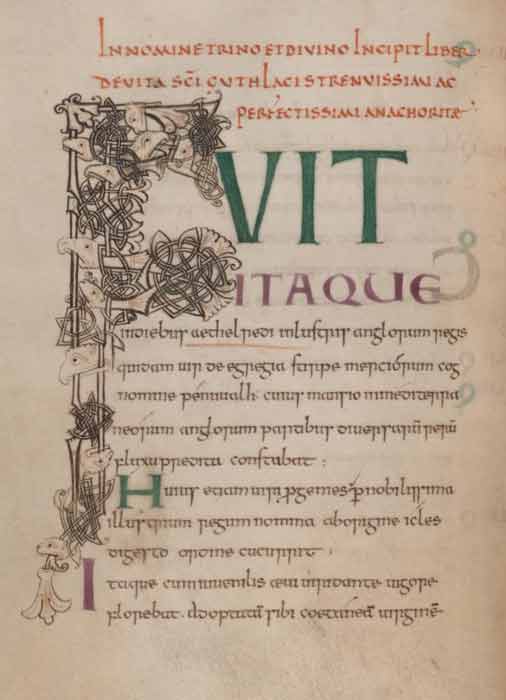

The beginning of Felix’s Life of St Guthlac. (Felix / Public domain )

St Guthlac As Boy and As a Teenager: A Promising Young Man

As a child, Guthlac is said to have been sharp-minded, obedient to his parent and caregivers, did not partake in vain talk or lying flattery, and was not “addicted to boyish levities” but was instead “innocent in his ways.” No doubt wanting to paint an image of Guthlac as a holy child, Felix most likely skipped over the details of his growing years that would have been considered less wholesome.

Medieval warriors like Guthlac began training for a military career early in childhood. The boy would learn to walk and to ride a horse simultaneously, expected to be a fully competent horseman by the age of seven. Young boys were raised in a homosocial environment, meaning everything they did was always in groups with other boys or men. Meals were communal, as were sleeping areas, and young boys were sent out hunting together in teams. Military training was conducted in groups as well to the build group loyalty that was key to a successful army.

When training was completed in his adolescence, a boy could become a knight, a rite of passage into manhood. But before he could become a man, a boy must prove himself among his peers. Military skill and a warrior’s disposition were seen as intrinsic to masculinity in the medieval period. So, in order to prove himself a man one must pursue military activities, usually in the form of real or simulated combat such as tournaments.

Guthlac was no different. No doubt having grown up in the company of many fighting men in his father’s household, once he reached the age of manhood he was inspired to collect a troop of his companions and lead them in the pursuit of manly activities.

St Guthlac was a fierce medieval warrior for nine years and during that time he murdered some and pillaged plenty, until he “saw the light.” ( zef art / Adobe Stock)

St Guthlac Emerges and Gives Back Some of His Loot

In Felix’s words, Guthlac’s gentle and innocent nature suddenly changed on the cusp of manhood:

“Thought he on the strong deeds of the heroes, and of the men of yore. Then, as though he had woke from sleep, his disposition was changed.”

The divine child, who had received the gift of eternal bliss from God, now became a warrior who reveled in violence and bloodshed: “wreaked he his grudges on his enemies, and burned their city, and ravaged their towns, and widely throughout the land he made much slaughter, and slew and took from men their goods.”

This was the life Guthlac had been raised for, and despite whatever ethical qualms Felix may have had, a sudden change of disposition was not the likely cause of Guthlac’s ambition to become a warrior. He was simply doing what was expected of him.

Where the story becomes interesting however, is that after nine years of leading this life of murder and pillaging , Guthlac appears to have had a sudden spiritual revelation, which caused him to feel remorse for his actions and prompted him to give back a third of all the goods he had stolen.

Following this revelation, Guthlac was then gifted a divine vision in which he perceived his own death, and the meaninglessness of a sinful life, and so he made a vow to God that night that if his life would be spared until morning, he would devote himself to God’s service. And so he did. The next day, he informed his troop that they should find a new leader, then left for the monastery of Hrypadun (modern-day Repton) where he took his tonsure and became a monk.

The quatrefoil above the west door of the Crowland Abbey shows four relief scenes from the life of St Guthlac. (Thorvaldsson / CC BY 3.0 )

St Guthlac: A Christian Hero Is Born

A vision of one’s own death is certainly a powerful reason to trade a medieval warrior’s life for one of religious solitude, but on its own not enough reason to declare someone a saint. Plenty of nobles and royals in the medieval period, after a life of military service and warfare, retired to monasteries to repent their sins and live out the rest of their days in peaceful prayer and contemplation. Few, however, went on to become saints.

The violence of warfare was recognized as a necessary evil if Christian society were to be allowed to flourish in peace, but for a warrior to revel in that violence or to seek vengeance through the shedding of blood went against the teachings of the church. The moral code by which a warrior lived was incompatible with Christian morality. A warrior was expected to be courageous, but also wise enough so as not to be proud or reckless, and he must always go into battle viriliter et sapienter , meaning “manfully (with courage) and wisely.” A monk on the other hand, was forbidden from shedding another man’s blood and was expected to live peacefully, receiving wisdom from God rather than from other men.

The Church tolerated necessary violence without condemnation but was reluctant to condone any sort of violence unless it was directed towards spiritual ends. In this way, the two disparate ideals could be reconciled. A warrior who fought in God’s name and for a Christian cause was worthy of esteem in the eyes of the Church, and thus was the idea of a “Christian hero” born.

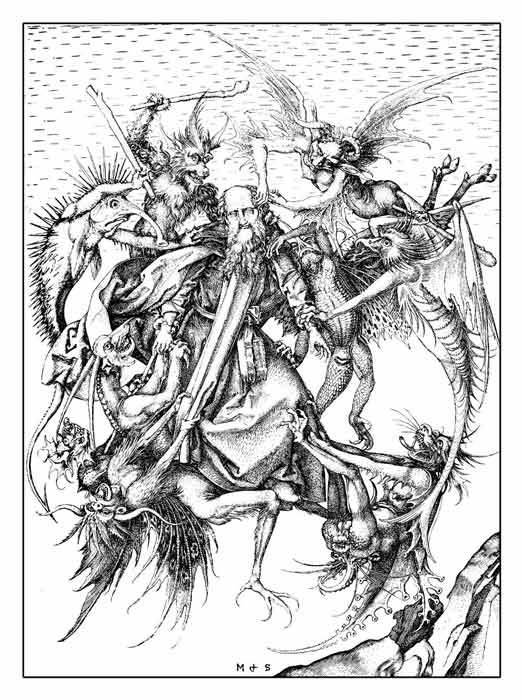

St Guthlac is presented with a whip by St Bartholomew as he is tormented by demons, an illustration from The Guthlac Roll. ( Public domain )

A War Waged for the Lord

Felix’s biography paints St Guthlac as the quintessential Christian hero, creating him as “a soldier of the true God” who “waged his war for the Lord.” St Guthlac’s spiritual “battles” are consistently described by Felix with military metaphors, so as to give the impression that he is fighting a holy war: “that he might arm himself against the attacks of the wicked spirits with spiritual weapons, he took the shield of the Holy Spirit, faith; and clothed himself in the armor of heavenly hope; and put on his head the helmet of chaste thoughts; and with the arrows of holy psalmody he ever continually shot and fought against the accursed spirits.”

So, St Guthlac’s violent nature is turned towards a noble, Christian cause and thus he becomes a man worthy of recognition by the Church. He has not yet, however, become worthy of saint hood.

It was where he chose to wage his holy war that made Guthlac saintly. Two years after entering the monastery, at the age of 26, Guthlac decided to leave the world behind and live in almost total solitude in the wilderness of Crowland’s marshes.

He heard from a man named Tatwine, of a particularly isolated island that, although many had tried, no man could inhabit on account of “manifold horrors and fears,” a place so lonely and wild that no man could endure it. As soon as Guthlac heard this, he bid goodbye to his brethren at Hrypadun (Repton) and set out in a boat, with only two servants for company, to make his home on the island and live the rest of his days as a hermit.

The Temptation of St Anthony (1470 AD engraving) in which the Christian monk Anthony the Great faces temptation is his desert pilgrimage, much like the trials St Guthlac experienced in the marshes of Crowland. ( acrogame / Adobe Stock)

St Guthlac: A Holy Man of the Desert in the Marshes

St Guthlac’s decision to withdraw from the world in this way may appear as eccentric to modern sensibilities, especially for a man who “had it all:” a knight from the noble class, descended from a distinguished royal line, successful in his military exploits and a leader of men. It seems less strange though when considering that he was participating in a well-established tradition of monks who lived an ascetic lifestyle. For hundreds of years, men and women had been shutting themselves away from the world, living in isolation and self-deprivation as part of the practice of asceticism.

The original ascetics usually made their homes in the desert, as they mostly came from Egypt where the “wilderness” that surrounded their civilizations was made of sand and rock, not marshland. The most famous of these “ Desert Fathers ,” as they came to be known, was St Anthony the Great, who lived from about 251-356 AD and moved into the desert in 270-271. Other well-known Desert Fathers include St Simeon the Stylite, a Syrian ascetic who lived for 37 years on the top of a pillar in the 5th century, and St Paul the Hermit, who supposedly lived almost 100 years in a cave near Thebes at around the same time as St Anthony.

While St Guthlac did not live in a literal desert, he nonetheless endured the self-deprivation and frugality as was the nature of an ascetic lifestyle and thus his island in the marshes became his metaphorical “desert.”

It was a harsh way of life, and Felix describes the ways in which St Guthlac showed his faith in his determination to endure: “he resolved that he would use neither woolen nor linen garment, but that he would live all the days of his life in clothing of skins…he never tasted aught but barley-bread and water; and when the sun was set, then took he his food on which he lived.” He washed only once every 20 days and passed his time mostly in prayer.

St Guthlac was never truly alone during his time on the island, as he was always accompanied by his followers and servants, and once it became known that he possessed both the power of prophecy and the power of healing, visitors came from all over England to seek him out. Even Aethelbald of Mercia, whilst still a nobleman and in exile, came to seek the counsel of the holy man St Guthlac, who prophesied that he would soon be crowned king, and he was in the year 716.

St Guthlac was a man of many faces, the lord’s son, the war hero, the monk, the hermit, who led a remarkable life. His deeds earned him immense fame throughout the medieval period and his feast day, on the 11th of April, was widely celebrated in parts of England for centuries.

His life may also serve as inspiration for a modern reader in many ways: a man who found himself dissatisfied with his life, made difficult choices that went against the expectations of his society and eventually found spiritual completeness and peace within himself. What could be more saintly than that?

Top image: Medieval hermit. Source: Thomas Mucha / Adobe Stock

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Bennett, M. “Military Masculinity in England and Northern France c.1050-c. 1225.” 1999. In Masculinity in Medieval Europe , ed. D. M. Hadley. New York: Addison Wesley Longman Limited.

Felix of Crowland. Life of Saint Guthlac . 1848. Ed. and trans. Charles Wycliffe Goodwin. London: John Russell Smith.

O’Keeffe, Katherine O’Brien. “Heroic values and Christian ethics.” 1991. In The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature , ed. M. Godden and M. Lapidge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 13th, 2021

April 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: