So, on an arid Saturday morning this past summer, the sisters piled into a friend’s pickup truck and headed for a Clayton Homes sales lot here just outside the impoverished Navajo reservation.

The women — one in a long, colorful tribal skirt, another wearing turquoise jewelry, a traditional talisman against evil — were steered to a mobile home sales agent who spoke Navajo, just like the voice on the store’s radio ads.

He walked them through Clayton-built homes on the lot, then into the sales center, passing a banner and posters promoting one subprime lender: Vanderbilt Mortgage, a Clayton subsidiary. Inside, he handed them a Vanderbilt sales pamphlet.

“Vanderbilt is the only one that finances on the reservation,” he told the women.

His claim, which the women caught on tape, was a lie. And it was illegal.

It is just one in a pattern of deceptions that Clayton has used to help extract billions from poor customers around the country — particularly people of color, who make up a substantial and growing portion of its business.

The company is controlled by Warren Buffett, one of world’s richest men, but its methods hardly match Buffett’s honest, folksy image: Clayton systematically pursues unwitting minority home buyers and baits them into costly subprime loans, many of which are doomed to fail, an investigation by BuzzFeed News and the Seattle Times has found.

Clayton’s predatory practices have damaged minority communities — from rural black enclaves in the Louisiana Delta, across Spanish-speaking swaths of Texas, to Native American reservations in the Southwest. Many customers end up losing their homes, thousands of dollars in down payments, or even land they’d owned outright.

Over the 12 years since Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway bought Clayton Homes, the company has grown to dominate virtually every aspect of America’s mobile-home industry. It builds nearly half the new manufactured homes sold in this country every year, making it the most prolific U.S. home builder of any type. It sells them through a network of more than 1,600 dealerships. And it finances more mobile-home loans than any other lender by a factor of more than seven.

In minority communities, Clayton’s grip on the lending market verges on monopolistic: Last year, according to federal data, Clayton made 72% of the loans to black people who financed mobile homes.

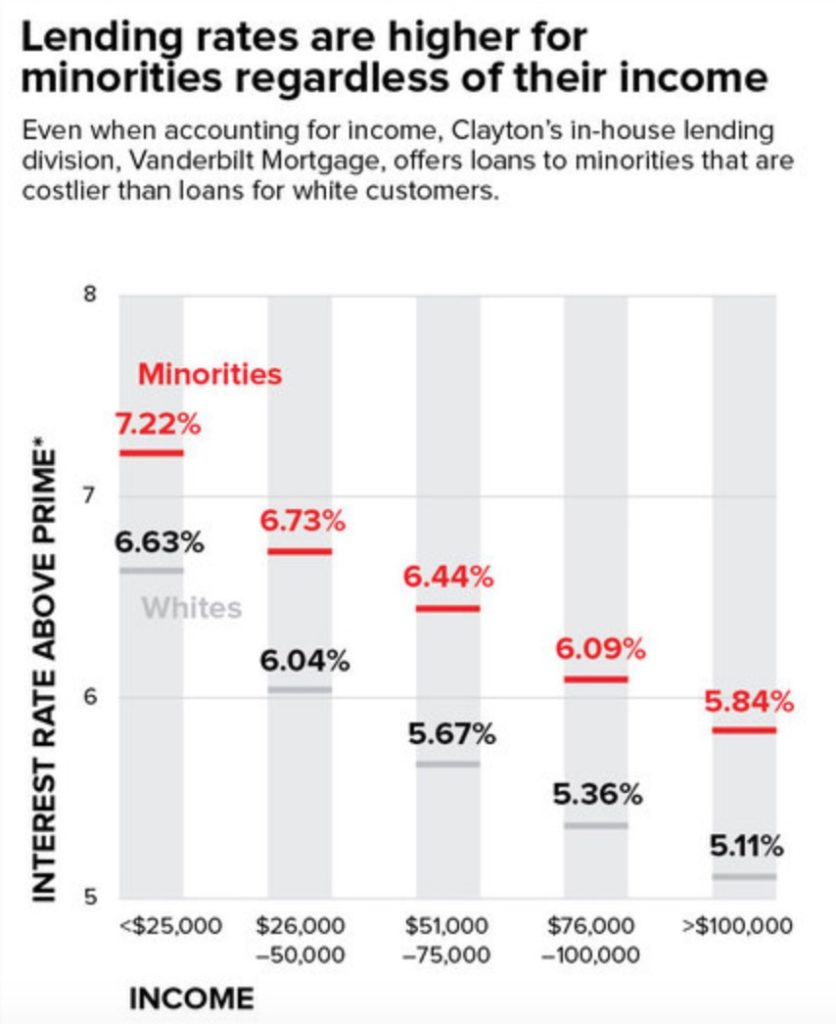

The company’s in-house lender, Vanderbilt Mortgage, charges minority borrowers substantially higher rates, on average, than their white counterparts. In fact, federal data shows that Vanderbilt typically charges black people who make over $75,000 a year slightly more than white people who make only $35,000.

Through a spokesperson earlier this month, Buffett declined to discuss racial issues at Clayton Homes, and a reporter who attempted to contact him at his home was turned away by security.

Clayton and Berkshire Hathaway did not respond to numerous requests for interviews with executives, delivered by phone and email, as well as in person at Berkshire Hathaway’s headquarters in Omaha. The companies did not answer any of 34 detailed questions about Clayton and its practices. Nor did they respond to an extensive summary of this article’s findings, provided along with an invitation to comment.

As it drew in more Latino customers, however, Clayton’s practice was not to provide Spanish-speaking customers with translated loan documents or interpreters at closing — even after employees at headquarters complained that too many customers were being misled about loan terms.

For an earlier story detailing Clayton’s widespread abuse of borrowers, a Clayton spokesperson said that the company helps customers find homes within their budgets and has a “purpose of opening doors to a better life, one home at a time.” Buffett later defended the company, telling Berkshire Hathaway shareholders he makes “no apologies whatsoever about Clayton’s lending terms.”

For this story, BuzzFeed News and the Seattle Times analyzed hundreds of internal company documents, thousands of legal and regulatory filings, more than 40 hours of internal company audio recordings, and federal data on hundreds of thousands of mobile-home loans over a decade. Reporters conducted interviews with more than 280 customers, employees, and experts, including some Clayton insiders who said they were appalled by the company’s practices.

Meanwhile, in the first nine months of this year, Clayton generated more than half a billion dollars in profit, up 28% from the same period last year.

“I’m almost a 60-year-old man,” he said earlier this year. “It’s the first time — living in Arkansas my whole life — and it was truly the first time that I had experienced true racism.”

In at least six states, Clayton managers have permitted open racial hostility toward people of color, according to interviews and legal filings by more than 15 former workers with direct knowledge of the incidents. In at least seven cases documented in court records, sales reps — both black and white — were fired after complaining about racism on the job. Four cases were dropped or dismissed, and Clayton settled three.

“I can’t help myself, I hate niggers,” McNeal’s main harasser told a contractor on the sales lot, according to a separate lawsuit filed by the two white co-workers. One of them remembered the harasser calling the sales lot “niggerville” when black customers arrived to tour homes.

One of the Navajo women at the Gallup lot recorded audio of their shopping experience, including the exchange in which a sales agent told them Vanderbilt was the only financing option on the reservation. Even after being told of the recording and its contents, Shaw insisted that his employees follow the law.

The Navajo Nation itself also offers loans to finance mobile homes. Louise Johnson, the head of the Navajo Nation’s credit services division, said Native leaders developed the program after seeing widespread repossessions of mobile homes on the reservation. Her division offers mobile-home loans with an interest rate often under 6.5% — half the rate paid by many Clayton borrowers. Yet few Navajo buyers end up borrowing from the tribe.

When he defended Clayton’s compliance with the law earlier this year, Buffett said the company’s lots use “lender boards” on their walls to show buyers the array of finance options to choose from. But the lender board at the Gallup lot, just five miles from Native territory, had no information about Navajo credit services. It did list a lender that participates in the federal program. In an interview, however, Shaw dismissed the program as a poor option for many borrowers.

“Vanderbilt wants to finance your home. Fast approval. Friendly service. And less than perfect credit accepted,” a voice says. “Choose Vanderbilt!”

Vanderbilt and Clayton’s other lending division, 21st Mortgage, originated 53% of all mobile-home loans to Native Americans, 56% of loans to Latino and Hispanic borrowers, and 72% to blacks, according to 2014 federal loan data from some 7,000 lenders. Among white borrowers who were not also identified as Latino or Hispanic, Clayton’s market share was 31%.

Clayton was less reliant on lending to minorities in 2004, the first full year after Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway bought the company for $1.7 billion. Around that time, then-marketing manager Robert Fox explained in a recent interview, Clayton was beginning to harness emerging research tools to help identify untapped markets.

Another lot’s Spanish-language ad addressed immigrants who have government tax ID numbers but no Social Security number: “No credit, no Social! Your ITIN and your promise is all we need!”

But when the time came to sign a legally binding loan, the company’s Spanish language skills disappeared: Its practice was to provide loan documents, full of dense legal jargon, in English and not to provide interpreters, according to 12 Spanish-speaking borrowers who purchased homes in Texas over the past few years.

That’s how Rocio Orozco, a single mother living in rural Willis, Texas, who speaks only enough English to carry on a simple conversation, said she ended up paying nearly double the interest rate she was promised — and losing $500 of her down payment to her local Clayton-owned dealer before she’d even signed the contract.

She expressed further dismay when the reporter noted that she is paying a 14.2 annualpercentage rate on the 20-year loan. The sales agent had told her she was approved at 8%, Orozco said. At the loan closing, the title agent referred by Clayton rushed her through the process, showing her only the blanks on pages requiring her signature, Orozco said.

Gwen Schablik said stories like that make her blood boil. Schablik was one of a handful of Spanish speakers working in collections at Clayton back in 2012. Every week, she said, she took calls from people whose weak command of English led them to sign loan documents they couldn’t understand.

Managers and executives, she said, dismissed her concerns; she recalled one replying, “It doesn’t really matter as long as we get the money.”

Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans tend to have lower median incomes and lower credit scores than white Americans. As a result, the loans they receive — for houses, cars, or virtually anything else — often have higher interest rates. So Vanderbilt is not alone in charging minority customers more, on average, to finance their mobile homes. What sets the company apart is just how much more.

The gap between Vanderbilt’s disclosed interest rates for whites and those for minorities — more than 0.7 percentage points on the annual rate — is the largest among big mobile-home lenders. That difference can amount to thousands of dollars over the life of an average loan. The disparity persists even after adjusting for income: Minority borrowers earning between $75,000 and $100,000 on average pay interest rates slightly higher than those paid by Vanderbilt’s white borrowers making only $25,000 to $50,000, according to a BuzzFeed News–Seattle Times analysis of recent federal loan data.

The practice may violate the federal Fair Housing Act or the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, said Relman, who represented the city of Baltimore in a suit against Wells Fargo for reverse redlining. (The bank, which did not admit wrongdoing, settled, agreeing to spend millions of dollars on housing initiatives.)

Even when loans go bad quickly, the sale can be profitable for Berkshire Hathaway. Clayton often marks up new homes about 70% over invoice, company documents show. After a 20% down payment and thousands of dollars in fees added into the loan, Clayton can recoup more than half the wholesale price of the home in a year.

When borrowers stop paying, the company can repossess and resell the home, again with another markup.

Source Article from http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/blacklistednews/hKxa/~3/Emf0-M6ZZBs/M.html

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 26th, 2015

December 26th, 2015  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: