Almost everyone at the Istanbul Topkapi Palace was a slave, but this is not the only curious attribute the palace had when ruled by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Everyone was forced to learn and use only sign language. Why could this be? This article examines how sign language was first introduced at the Topkapi Palace under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and why sign language was exclusively spoken at the palace. Topkapi Palace was not a special school for the deaf, but a unique place for everyone, both hearing and deaf residents alike.

This paper also covers the factual issues about harems. Inadvertently a vow of silence may seem a divergence, but be assured, a vow of silence was a significant step in the terms of speaking sign language and educating people who were deaf.

The older empires prior to the Ottoman Empire shared similar customs and rituals, which were unlike European customs. These ancient empires were always about including deaf people and “gestures of mutes” (sign language). These are very ancient customs and nothing about them was “new.” As with all other declines, the end of Ottoman Sign Language (OSL) and the empire were unavoidable outcomes.

Suleiman the Magnificent. Hungarian National Museum. (Yelkrokoyade / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Topkapi Palace And Slavery In the Ottoman Empire

At the peak of the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman the Magnificent (reigned 1520-1566), there were 4,000 residents at the Topkapi Palace, and the majority were slaves, as slavery in the empire was unfortunately legal.

“Slavery was a legal and significant part of the Ottoman Empire’s economy and traditional society” (Cambridge World History of Slavery).

In Istanbul, the administrative and political center of the Ottoman Empire , the population of slaves was around 2.5 million from 1453 to 1700 AD.

“By raising and specially training slaves as officials in palace schools such as Enderun, where they were taught to serve the Sultan and other educational subjects, the Ottomans created administrators with intricate knowledge of government and fanatically loyal. Those slaves and [manumitted (freed)] slaves were integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th century.” (Necipoglu and Habib)

Where Did The Ottoman Empire Slaves Come From?

The majority of slaves at the Topkapi Palace were captured from Christian territories conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under the empire almost every country was conquered through aggressive warfare and many captives became slaves.

The Ottoman Grand Vizier (the second most powerful man below the sultan) at one time was at the head of the household slave’ hierarchy. The sultan appointed the Grand Vizier and only the Sultan could dismiss the Grand Vizier.

The Grand Vizier’s chief advisor evaluated the enslaved according to the criteria issued by the sultan. One of the criteria required the enslaved to convert to Islam. Those who met the criteria were forced to leave the territory where they had been captured and taken to Topkapi Palace . Once they arrived at the palace, they began their training and lessons.

Residents from conquered Christian territories that had been enslaved and converted to Islam were frequently manumitted (freed) after several years of service, for such manumission counted as a pious act on the part of the slave owner. Common sense would suggest that they were obviously unhappy to be slaves and that they converted to Islam as a way to survive.

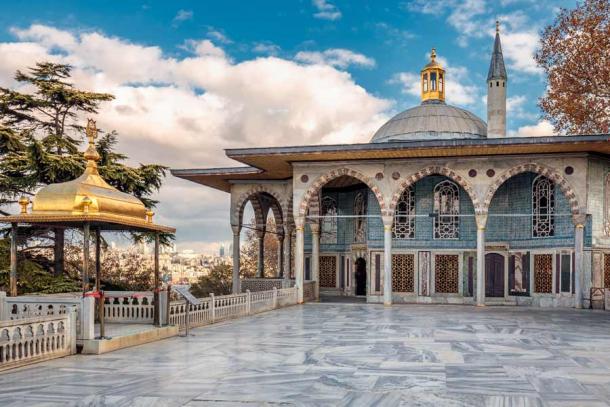

Upper Terrace and Bagdad Kiosk at Topkapi Palace ( RuslanKphoto / Adobe Stock)

What Did The Slaves Do At The Topkapi Palace?

Slaves as novices received religious and cultural indoctrination while learning to read, write, and speak Ottoman Turkish after which they were placed in the Sultan’s service. The curriculum included studying Koran, Arabic grammar books, silent lessons (sign language), law, Persian literary classics , and various forms of vocational training.

Once the trained slaves, who became pages (men who worked as servants to the empire and the sultan) had completed their training in the various chambers and proved their skills and loyalty in service to the sultan they were finally ready to take up distinguished administrative posts in the outside world.

They were also taught to train hunting dogs and falcons. The Topkapi Palace has its own hospital, laundry, mint, bakeries, seamstresses, tailors, barbers, hairdressers, embroiders, weavers, jewelers, house cleaners, carpenters, and most of these occupations were filled by trained slaves.

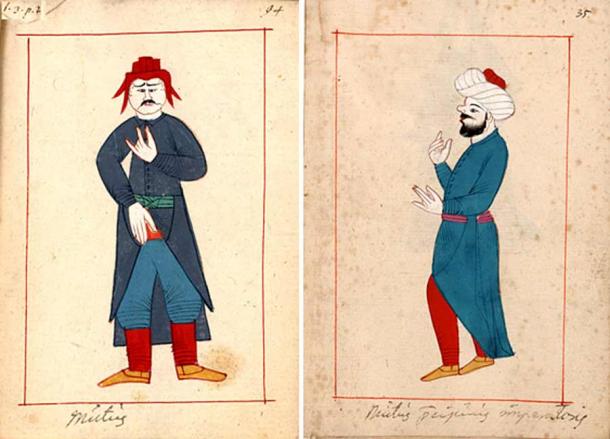

Ottoman mutes speaking their sign language. (Ralamb Costume Book, 1657 / Public Domain )

The Story Of The Ottoman Sign Language (OSL)

In 1522, Ottoman Sign Language (OSL) was first introduced to the palace by two mute brothers during the reign of Suleiman I. Finding this form of communication very respectful, the sultan ordered sign language to be used by all pages (slaves) attached to his privy chamber. For deaf people, their hands are their voice, their eyes are their ears.

Harvard Professor, Gulru Necipoglu, mentioned in her book, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, that:

“In 1527, Suleyman refused to speak, a silence certainly not observed by the Sultan’s forebears,…In his use of mute signs instead of words. Only three favorite pages were allowed to address him in words; the others could communicate only through signs.”

In 1605 the French diplomat, Henry de Beauvau says that this sign language was called “Ixarette” (in Turkish isaret means “sign”) and was used in the palace as a second language. Three years later in 1608 the Venetian bailo (a high ranking diplomat), Ottavin Bon wrote that “the Sultan and his pages communicate in sign language to observe the gravity so much professed by the Turks, and what they express with mute signs is more than is discussed vocally; the same is among the royal women and other ladies, for among them there are also old and young mutes; and it is a very ancient custom of the seraglio to desire and have as many mutes as can be found.” [mute here is synonymous with slave]

Nine years later in 1617, the sign language and Principle of Silence prescribed by Suleiman developed into a compulsory attribute of royal dignity. When Sultan Mustafa (reigned 1617- 1618 and 1622-1623) refused to learn it, he was criticized in the public council hall of Istanbul. Those who voiced their complaint saw it as undignified for a sultan to use the ordinary speech of Janissaries [slaves] and common merchants and agree he [sultan] should never talk, but make people tremble by his extraordinary gravity.

Room decorated with Cobalt blue Iznik tiles. (Jorge Láscar / CC BY 2.0 )

The Deaf Spaces Of The Topkapi Palace

The most surprising element of this research was coming across one of the credible sources that described the physical spaces at the Topkapi Palace that were incidentally friendly to speakers of sign language in which are currently known as “ deaf spaces ”.

According to Professor Necipoglu the primary sources described the physical spaces at the Topkapi known as deaf spaces as follows:

“Before going to bed, roll called, and then the Chamber master struck the floor with his walking stick to signal the hour of repose. In all dormitories, pages slept in small beds in long rectangular halls that were illuminated the whole night with torches, so that gate boys and eunuchs could watch their behavior.”

The phrase “…struck the floor with his walking stick” implies that pages (slaves) present were deaf. The act of striking the floor with a walking stick has been a common way of getting the attention of deaf individuals, even in the 15th century at the Topkapi Palace under Suleiman!

How precious it is to read this on record from nearly 700 years ago. Based on real life experience, deaf tenants reside on the, for example, second floor of an apartment, and whenever they unintentionally made annoying noises disturbing the hearing tenants below, they would strike the ceiling with a broom handle to alert deaf tenants upstairs to stop making the unintended annoying noises.

Hearing pages heard the stick hitting the floor precisely at the same time the deaf pages felt its vibration.

Based on my observations, when I visited the Topkapi Palace Museum, I noticed amazing honeycomb skylights in one of the halls, which I instinctively believed must be designed for the speakers of sign language. One aspect of the deaf spaces within the Topkapi Palace was lots of light: bright wide halls, and half-circle windows were strategically placed up high on either side quite close to the ceilings.

How The Concept Of Harems Has Long Been Misunderstood

Let it be known those credible sources also revealed that the Europeans of the past had misunderstood the basic concept of harems. New York University Professor Leslie Pierce explained in her book, Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereign in the Ottoman Empire , “In reality a family harem is an honorable sanctuary—religious purity—for women, their children, and Sultan. There is also a male harem.” Let’s be clear, harems were never brothels nor places for sexual orgies . Only the husband, the head of his household, is allowed inside the family harem.

Imaginary scene from the sultan’s harem. ( Public Domain )

It is natural to ask why Europeans of the past misconstrued harems, and this is likely due to the fact that some Christian territories were conquered, especially Constantinople. Christian Europeans of the past were bitter and angry about the loss of Christian Constantinople and the Hagia Sophia Basilica, the largest Christian church of that time. For Christians, it was such a devastating loss when Constantinople was conquered and renamed the city Istanbul and converted into a Muslim city. Hagia Sophia Basilica was renovated into a mosque and numerous Muslim mosques were built in the exact image of the renovated Hagia Sophia Basilica.

Realistically that is the norm of waging a war against an enemy and Constantinople was conquered by the non-Christian enemy. The conqueror gets the chance to change the city, and though Constantinople was an Orthodox Christian city, it was widely overhauled to reflect the Islamic religion of the conqueror. The revenge of the conquered Christian residents of Istanbul was that they twisted the meaning of one the caliphate’s most cherished values, their harems, from a sanctuary into sinful brothels and places of sexual orgies.

The True Nature And Reality Of The Topkapi Palace Harems

As Professor Leslie Peirce explained, “Toward the end of the sixteenth century, Sultan established a second set of private quarters in the palace precinct to house women and their children of the royal household, the latter area also began to be referred to as “the imperial harem” because of the presence there, not of women, but of the Sultan.”

Peirce describes how imperial harems were guarded as follows: “White eunuchs guarded the imperial male harem for young princes who were no longer young enough to stay in the family harem. The Black eunuchs guarded the imperial harem for women, children, and Sultan.”

Portrait Of Cameria, Daughter of The Emperor Soliman, (1522-1578) by Cristofano dell’ Altissimo. (Pera Museum, Public domain )

Remember Suleiman’s quote … “…it’s a very ancient custom of the seraglio to desire and have as many mutes as can be found…”

From the early beginnings of the vow of silence, monks and nuns living in monasteries were speaking sign language and teaching children who were deaf. Pierce’s book mentioned that the Ottoman Empire conquered Christian territories and, sure enough, monasteries were also located in the conquered areas of the Ottoman Empire. And historical evidence shows that Christian monasteries and churches welcomed deaf individuals, making of them a congregation of deaf Christians.

Early Educational Approaches Used For Deaf People

Marina Radic Sestic, Nadezda Dimic, and Mila Seum at the University of Belgrade, Serbia, mentioned in their 2012 article, The Beginnings of Education of the Deaf Persons: Renaissance Europe 15th – 16th Century (page 147) that “It’s a well-known fact that handicapped persons were marginalized in the Middle Ages by the broader social community and that charitable care within churches and monasteries was considered to be a legitimate form of help to those who were designated by God to expiate the sins of their ancestors.” Actually, it was Aristotle who first made the wrongful claim that God expiates the sins of the ancestors of deaf people.

Gallaudet University English Language Professor, Lois Bragg wrote in her article, Communication in Europe Before 1600: Lexicon [signing] and Finger Alphabets Prior to the Rise of Deaf Education that “a vast majority of the deaf and the small number of deaf children of the nobility who were sent to Ona [Spain] or, indeed, any monastery at any time since the introduction of lexicons. In other words, even if a handful of elite deaf youths emerged from monasteries knowledgeable in cloistral signing, they may unlikely have any contact with deaf people of other social classes…”.

Marilyn Daniels’ book, Benedictine Roots in the development Deaf Education: Listening with the Hear t revealed that the Benedictine involvement with the development of deaf education is not well known, which is exactly what Lois Bragg explained in her article.

The Slow Decline of Ottoman Sign Language and the Empire

Because Sultan Mustafa refused to learn sign language, it slowly diminished and was used less and less by subsequent sultans. However, I believe that exterior world politics may also have influenced the sultans after Suleiman to reconsider the ideas of silence and the deaf in new ways.

While the Ottoman Empire was impressive for much of its 499 years of existence, how the Ottoman Empire conquered territories was less than admirable. The way they enslaved countless individuals all over the empire was horrible. And though slavery is wrong, the slaves of Topkapi Palace had it pretty good. They were given an opportunity to advance themselves and to prepare themselves for employment in the outside world.

There were much worse places to be living as a slave. ( muratart / Adobe Stock)

Throughout 46-year reign, Suleiman progressively preferred to always sign to the point that OSL was exclusively spoken as a second language at the palace. They “spoke” in OSL much more than what was discussed vocally. He wanted to have as many mutes as could be found. It leads me to wonder if Suleiman himself was slightly deaf and tried to hide his weakness by embracing it.

There are a few pre-World War I sources written by deaf intellectuals hoping for a utopian world in which everyone understood deaf people and spoke their language.

Obviously, Suleiman was fluent in OSL. Topkapi Palace was indeed a utopia for deaf people; however, possibly not for all hearing people.

Top image: Throne room in the Topkapi Palace harem, Istanbul. Source: Francesco Bonino / Adobe Stock

References

Bragg, L. (1997). Visual-Kinetic Communication in Europe Before 1600: A Survey of Sign Lexicons and Finger Alphabets Prior to the Rise of Deaf Education . Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2(1), 1-25. Retrieved March 19, 2021, Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23805404

Campus Design and Planning Deaf Space . Gallaudet University. Available Online:

https://www.gallaudet.edu/campus-design-and-planning/deafspace/

Daniels, Marilyn (1997) Benedictine Roots in the Development of Deaf Education: Listening with the Heart. Bergen & Garvey. Westport, Connecticut.

Earls, Averill. (2018) Devsirme: The Tribute of Children, Slavery and the Ottoman Empire. Available online:

https://digpodcast.org/2018/08/26/devsirme-the-tribute-of-children-slavery-and-the-ottoman-empire/

Habib Abdullah (2012) A Full Report about Enderun Ottoman School. Available online: https://turkpidya.com/en/enderun-ottoman-school/

Lane, Harlan. Deaf Experience: Classics in Language and Education. Gallaudet University. Washington, DC. Available online: http://gupress.gallaudet.edu/excerpts/TDE.html

Necipoglu, Gulru. (1991) Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries . MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England.

Available online: https://biography.yourdictionary.com/osman-i

Peirce, Leslie P. (1993) The Imperial Harem:Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. New York and Oxford.

Ree, Jonathan. (1999) I See a Voice: Deafness, Language and the Sense—A Philosophical History.

University Press. New York and Oxford.

Sanders, Paula. (1984) Ritual, Politics, and the city in Fatimid Cairo . State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

Sestic, Marina; Dimic, Nadezda; and Sesum, Mia. The Beginnings of Education of the Deaf Persons: Renaissance Europe, 15th – 16 th Century . (2012) University of Belgrade, Serbia. Available online:

Toledano, Ehud R. (2011) The World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420-1804. Available Online:

Zelazko, Alicja, (2017). Topkapi Palace Museum. Britannica. Available online:

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 21st, 2021

March 21st, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: