When one of us began studying psychology he was told that if the aim was to understand human relationships, it would be better served by studying literature—especially Shakespeare. Since then, at least as concerns clinical psychology , the subject has moved on to become an evidence-based humanistic alternative to psychiatry’s rather mindless medical model. Yet some of Shakespeare’s insights do still remain unrecognized. Despite all the innumerable treatises on Shakespeare, there is a near absence of any discussion of what can be inferred from his works concerning his view on the paranormal.

Hark! Consciousness and Entanglement

Most of us know the quotation from Shakespeare’s ” There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy (Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5) but very few scientists have actually taken this on-board. So let’s use this axiom to look at a fascinating area: Consciousness.

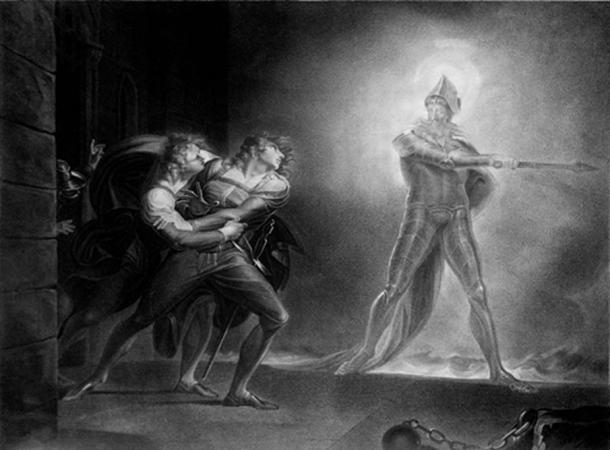

Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus, and the Ghost, on the platform before the Palace of Elsinor. 1796 ( Public Domain )

While there exists no accredited work integrating modern physics and psychology, there now is at least a “quantum biology” relating to biological molecules that show a dynamic form of “entanglement”— that is a resonance with each other across time and space that is not explicable by casual laws. If entanglement is found to have a pervasive role in nature, then given these forms of resonance occur in one brain then they may well occur between separate brains. Suddenly, the paranormal becomes normal science!

Indeed, should the author and physician Larry Dossey be right then these developments are not just academic; they would have implications that will revolutionize modern medicine.

Shakespeare’s Knowing Ghosts

What does Shakespeare, whose works contains 14 ghosts, have to say on the topic?

Macbeth seeing the ghost of Banquo. ( Public Domain )

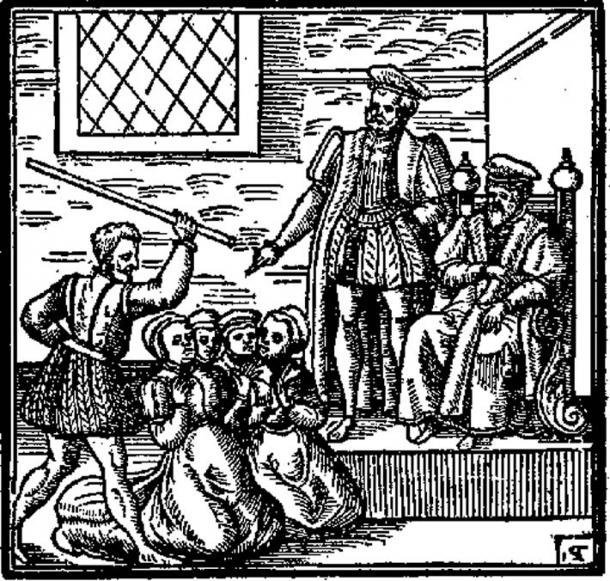

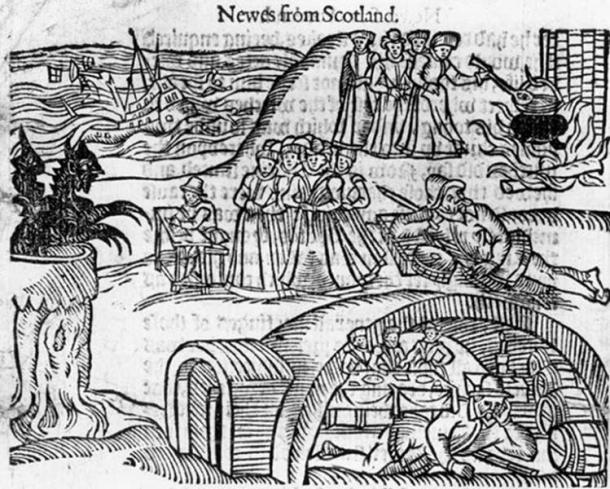

In order to evaluate Shakespeare’s writings, it is, of course, necessary to take into account the zeitgeist where a deviant idea could easily lead to the dungeon, if not decapitation. The Protestant Elizabethan period with its renaissance may well have offered greater freedom of expression for Shakespeare than the subsequent reign of James I. Although James was a Protestant, he was also James VI of Scotland where Calvinism and Catholicism were prevailing. Moreover, James took a very personal interest in witchcraft because spells were to have interfered with his marriage arrangements, causing heavy storms so that his fiancée’s ship from Copenhagen ended up at Oslo rather than Leith.

The North Berwick witches were accused and burnt for conspiracy involving the devil. James attended one of the trials, dismissing at first the involvement of the devil until one of the witches convinced him of her powers, unwittingly sealing her fate, by telling him the precise words his finance had whispered into his ear. The witches in Macbeth closely resemble the descriptions found in the records of the North Berwick witch trials.

Suspected witches kneeling before King James; Daemonologie (1597). ( Public Domain )

For Catholics and Calvinist’s sympathizers, there was one exception to seeing ghosts as agents of the devil; this was if God had a purpose in allowing the ghost a leave of absence from purgatory. Protestants added one further, more modern alternative: delusions of distraught minds. Hamlet was written very shortly before the ascendency of James to the throne and the ghost appears only because he has a leave of absence from purgatory, and the delusion aspect plays a major role in the play.

The North Berwick Witches meet the Devil in the local kirkyard, from a contemporary pamphlet, Newes from Scotland. ( Public Domain )

Evil Spirits

The plays Julius Caesar and Richard III are from the Elizabethan period. In Julius Caesar (Act IV scene 3) , Brutus confronts the ghost, demanding: ” Speak to me what thou art .” and the answer is: “Thy evil spirit, Brutus”. What is particularly profound here lies in the answer “Thy evil spirit”. This saying that while it is Brutus’s own consciousness that has produced the ghost, the entity has an independence of Brutus. The entity then foretells how they will meet again at Philippa—which is where Brutus will die.

This independence of the spirits reoccurs in Richard III (Act V scene 3) before the Battle of Bosworth Field when a succession of ghosts simultaneously appear the dreams of both Richard and his adversary, Richmond. The ghosts torment Richard but encourage Richmond in the fight by foretelling that he will become king and beget future kings.

David Garrick as Richard III by William Hogarth (1745). ( Public Domain )

This underlying idea is close that of “thoughtforms”—dynamic forms of thinking which can take on their own identity. Around Shakespeare’s time the Flemish physician, Jan Baptist van Helmont (1579-1644), was proposing that real spirits are created by the imagination. The idea is not a culturally bound one. It occurs, for instance, in Tibetan Buddhism as “tulpas” (a thoughtform, or being created from the collective thoughts of separate individuals) which are said to be easy to create but can become autonomous and empowered. Puck, one of the central characters in Midsummer Night’s Dream , seems to derive from the Irish goblin “phooka”, the Welsh “pwca”, the German goblin “Pück” and the Scandinavian “Puke”.

Puck, or Robin Goodfellow, from William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. (c. 1810–1820) is one of Henry Fuseli’s more sinister depictions of the character. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Perhaps the most well-known example in modern Western culture of thoughtforms is the imaginary rabbit in the film Harvey (1950). Harvey is a six-foot-four white rabbit “pooka” from Celtic folklore who is an imaginary friend of an eccentric. At first, Harvey is only seen by the eccentric, but soon develops his own life and others begin to see him. The “tulpa” can even appear as a feature of hypnosis. The Harvard educated psychologist George Estabrooks claimed to be able to produce through group hallucinations an imaginary polar bear on a hospital ward, who, like Harvey, developed his own existence and his own willpower.

From the film ‘Harvey,’ 1950. ( Source)

Ghosts, Poltergeists, and Strange Disturbances

A further feature of our book project ( Shakespeare’s Ghosts Live: From Shakespeare’s Ghosts to Psychical Research ) was to reclaim some of the relatively unknown accounts in rare books of spontaneous cases of ghosts and poltergeists from the Shakespearian period onwards and compare then to modern cases.

An example of a remarkable older poltergeist case took place in the 1600s in Rerrick, Scotland. Fourteen witnesses tell of seeing apparitions and poltergeist phenomena: stone throwing, raps, fire setting, movement of furniture, and the disturbance of animals. The case is similar to the modern Enfield case in that some of the phenomena were dangerous, if not potentially lethal, so whatever lay behind such cases, the perpetrators possessed extraordinary throwing skills in order not to cause serious bodily harm.

Ghostly apparitions. ( Public Domain )

How do we explain such cases? We all know from multitasking that our “sense of our self is far from unitary. If part of the self is activated by destructive motives which are seen as alien to “the reigning self” then during periods of religious repression and gross denial of human needs and integrity “all hell can break loose”.

There may be more to this. With the help of local history societies, we found cases where the ghost gave inexplicably correct details of a murder. The apparition of the murdered Anne Walker in 1630 from Lumley, County Durham appeared to an owner of a Mill not far from where it correctly told the body and clothes could then be found. It claimed Anne had become pregnant and murdered by a named man, who then because of this was brought to trial and executed.

The remains of the mill at Lumley. (© Adrian Parker 2017)

Albeit those accounts show recurrent features; are they mere deception and delusion? If the considerable laboratory-based evidence for the existence “extrasensory perception” is taken seriously, then there could be implications of a viable theory of what consciousness is.

To Sleep, To Dream

Shakespeare’s well-known quotation from Hamlet is fitting: ” To die, to sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream — ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come..” Neuroscientist and Nobel Prize winner Arvid Carlson speculated recently about what happens when you die: “We perhaps experience something which does not have any aspect of time—a state where the brain ceases to function and which is completely freed from an experience of time. And what is this? It is a sense of eternity.”

Contemporary physics is still very divided as to the ultimate nature of reality but some leading physicists such as Max Tegmark regard consciousness as important to their theories. It is generally acknowledged that the most influential psychologist was not a psychoanalytic or a cognitive psychologist, but the philosopher William James. It was James who, through his studies of altered states of consciousness and mediumship, arrived at the conclusion that the universe is pluralistic and consciousness is transcendental.

The above Shakespeare “More things in heaven and earth” quotation has a lasting relevance. Shakespeare is the most cited person throughout recent history and yet no one pays attention to his views on psychic phenomena. Our mission is to change this.

Annekatrin Puhle holds a doctoral degree in philosophy from the Free University of Berlin and is a freelance writer. Adrian Parker is a clinical psychologist and em. professor at the University of Gothenburg.

Their book Shakespeare’s Ghosts Live is published by Cambridge Scholars www.cambrigdescholars.com

Get their book at a discounted price at Cambridge Scholars Publishing – USE CODE: GHOSTS17

—

Top Image: The ghost in Hamlet is one of Shakespeare’s most famous ghosts. Source: Archivist /Adobe Stock

By Annekatrin Puhle and Adrian Parker-Reed

Updated May 7, 2021.

References

A leading representative of modern clinical psychology is Richard Bentall. See for example: Bentall, R. (2009) Doctoring the Mind . (2009) Penguin Books, London.

For the quantum biology see for example Lanza, R. (2009) Biocentrism: How Life and Consciousness are the Keys to Understanding the True Nature of the Universe. Dallas, TX: BenBella Books,

For convenient on-line sources of the evidence for psychic phenomena as studied in the laboratory, see: http://www.deanradin.com/evidence/evidence.htm

Larry Dossey has written many books on this topic the most recent of which is his bestseller: Dossey, L. (2013) One Mind. How Our Individual Mind is Part of a Greater Consciousness and Why it Matters. Carlsbad, California: Hay House.

For George Estabrooks’ account of the polar bear, see: Estabrooks, G.H. (1957) Hypnotism. Revised Edition. New York: Dutton & Co. p. 93-94.

The interview with Arvid Carlson was published in Swedish in Forskning och Framsteg , 2014.

Tegmark; M. (2014) Our Mathematical Universe – My quest for the ultimate nature of reality . Penguin Books, London.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 8th, 2021

May 8th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: