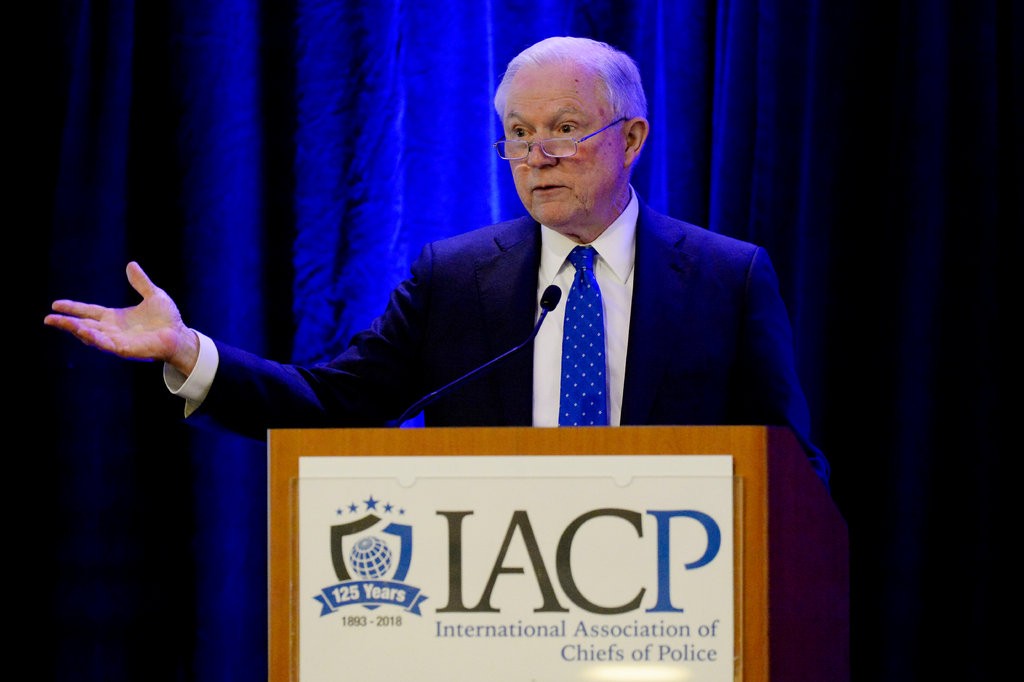

WASHINGTON — Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions has drastically limited the ability of federal law enforcement officials to use court-enforced agreements to overhaul local police departments accused of abuses and civil rights violations, the Justice Department announced on Thursday.

In a major last-minute act, Mr. Sessions signed a memorandum on Wednesday before President Trump fired him sharply curtailing the use of so-called consent decrees, court-approved deals between the Justice Department and local governments that create a road map of changes for law enforcement and other institutions.

The move means that the decrees, used aggressively by Obama-era Justice Department officials to fight police abuses, will be more difficult to enact. Mr. Sessions had signaled he would pull back on their use soon after he took office when he ordered a review of the existing agreements, including with police departments in Baltimore, Chicago and Ferguson, Mo., enacted amid a national outcry over the deaths of black men at the hands of officers.

Mr. Sessions imposed three stringent requirements for the agreements. Top political appointees must sign off the deals, rather than the career lawyers who have done so in the past; department lawyers must lay out evidence of additional violations beyond unconstitutional behavior; and the deals must have a sunset date, rather than being in place until police or other law enforcement agencies have shown improvement.

The document reflected Mr. Sessions’s staunch support for law enforcement and his belief that overzealous civil rights lawyers under the Obama administration vilified the local police. The federal government has long conducted oversight of local law enforcement agencies, and consent decrees have fallen in and out of favor since the first one was adopted in Pittsburgh more than two decades ago. The new guidelines push more of that responsibility onto state attorneys general and other local agencies.

Mr. Sessions conceded in his memo that consent decrees are sometimes the only way to ensure that government agencies follow the law. But he argued that changes were necessary because agreements that impose long-term, wide-ranging obligations on local governments could violate their sovereignty.

By setting a higher bar for the deals, Mr. Sessions limited a tool that the Justice Department has used to help change policing practices nationwide.

Mr. Sessions’s new guidelines make it nearly impossible for rank-and-file Justice Department lawyers to use the agreements, warned Jonathan M. Smith, a former official in the department’s civil rights division and the executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs.

“This memo will make the Justice Department much less effective in enforcing civil rights laws,” Mr. Smith said.

A Justice Department spokeswoman declined to comment beyond the memo.

A consent decree is a type of injunction that allows federal courts to enforce an agreement negotiated between two parties — say, the Justice Department and a local police department — to address a violation of the law. The department started enforcing them during the Clinton administration, after a statute was enacted in 1994 allowing the attorney general to use court agreements to remedy systemic, unconstitutional behavior.

The agreements gained a higher profile as the Obama administration entered into 14 of them as part of its efforts to improve relationships between the police and their communities. They became even more prominent after the killings of black men at the hands of the police captured headlines and set off the Black Lives Matter movement.

In March 2017, a month after he took office, Mr. Sessions ordered a review of the use of consent decrees to ensure that they “advance the safety and protection of the public.” He said that the pacts should also ensure that the police are safe and respected and that they should not interfere with recruiting efforts by the local police.

Mr. Sessions, who has long championed local sheriffs and police officers, maintained that the agreements “reduce morale” among police officers and lead to more violent crime. Academics and researchers have contested his assertions about the links between consent decrees and crime rates.

Under Mr. Sessions, the department also dropped Obama-era investigations into the police in Chicago and Louisiana.

Last month, Mr. Sessions opposed a consent decree between the Chicago Police Department and the Illinois attorney general enacted after a Justice Department report unveiled in the final days of the Obama administration found rampant use of excessive force aimed at black and Latino people. Under Mr. Sessions, the Justice Department said the deal placed too many restrictions on Chicago’s police superintendent.

“When Jeff Sessions intervened in the locally negotiated consent decree in Chicago, it belied the love of federalism that he professes and uses to justify this effort to effectively end the use of consent decrees,” said Vanita Gupta, the chief executive of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and the former head of the Justice Department’s civil rights division.

The agreements enacted after high-profile police killings in recent years would likely not exist if Mr. Sessions’s restrictions had been in place.

“The need for consent decrees and the oversight they guarantee,” she said, “has not disappeared.”

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/08/us/politics/sessions-limits-consent-decrees.html

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 9th, 2018

November 9th, 2018  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: