A medieval toilet may not be the first place you’d want to dig as an archaeologist, but old latrines are surprisingly good at revealing secrets to life in the Middle Ages! A team of scientists looking at medieval gut bacteria samples from two ancient toilets have reported on what is the first scientific attempt to detect ancient gut bacteria in this not-so-fun way.

The study was launched to determine what exactly constitutes a healthy microbiome for modern people. And to answer this question a team of researchers studied the microbiomes of our ancestors who lived long before antibiotics were in use and who didn’t eat any processed foods at all. The results of the experiment shed important light on the health of people in the Middle Ages.

An ancient public toilet from early Roman times, which would have been an excellent source of medieval gut bacteria. Source: cascoly2 / Adobe Stock

Studying Medieval Gut Bacteria To Understand Modern Health

Dr Piers Mitchell from Cambridge University recently published the findings of the new research on medieval gut bacteria in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B , and the results provide new insights into the gut microbiomes of pre-industrial agricultural populations. Dr Mitchell told Ars Technica “ We chose the two sites in Jerusalem and Riga in Latvia as they were both from the same time period but from different geographic regions,” which he suspected might lead to different microbiomes in those populations.

According to the Dr Mitchell, the approach taken in this study provides a new framework for determining the health of modern gut microbiomes. He explained that his team set out to determine what constitutes a healthy microbiomes in modern people, and also to analyze the microbiomes of our ancestors who lived and died before “antibiotics, fast food, and the other trappings of industrialization.” When these waste pits ( latrines) were in use, the areas surrounding them were urban, but not industrialized, and this means the ancient residents of such places probably ate and digested food differently than today’s urban city dwellers.

The human gut microbiome is a key part of human health, but it has changed over the centuries. In some ways, the medieval gut bacteria of ancient people was a healthier mix than what modern people have. (sdecoret / Adobe Stock )

Looking For Signatures In 600-Year-Old Poop DNA

According to an article in the Jerusalem Post , gut microbiomes encompass all of the microbes found in the intestines, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. And by studying medieval gut bacteria, the scientists were able to track changes in diet and digestion over time, which in turn, provided a better way of determining the health of modern human microbiomes.

Before the experiments were conducted not everyone was convinced that the study was a useful approach. Among the skeptics was Dr Kirsten Bos, a specialist in ancient bacterial DNA from Germany ’s Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. According to a report in Cosmos Magazine , while professor Bos had initial reservations about the feasibility of investigating the contents of latrines that had been unused for such a long time, she ended up as a co-lead author of the new paper.

Dr Bos was initially skeptical because in the beginning the scientists were not sure if the molecular signatures of gut contents would even survive in the latrines over several centuries. And while many projects that have retrieved ancient bacteria samples from calcified bone and dental tissues, Bos says these types of samples “offer very different preservation conditions.” However, despite these doubts, the team proceeded to collect and analyze sediment from 14th-15th century AD latrines in Jerusalem, Israel and Riga, Latvia.

The Various Medieval Gut Bacteria Types Found In The Study

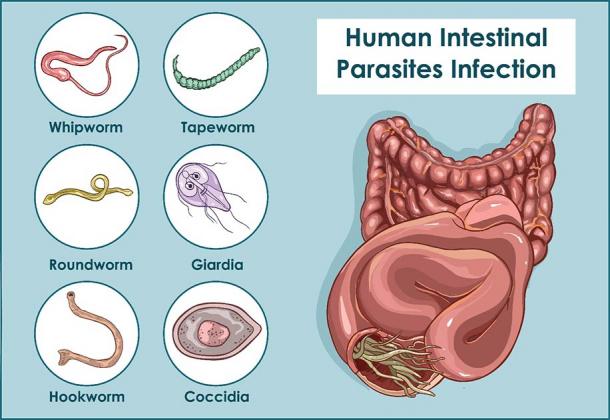

The first step in this experiment was to identify bacteria that had formed in ancient people’s guts as opposed to those naturally occurring in the soils at the latrine sites. The researchers found the poop of many people mixed together in the latrines, which they say offers insights into the microbiomes, and therefore the diets, of the entire communities. “Archaea, protozoa, parasitic worms, fungi” and other organisms were all discovered and listed in the paper along with taxa, which inhabit the intestines of modern humans.

These are just a few of the parasitic worms and other life forms that can live in our gut bacteria and harm us, and this was true a thousand years ago and today. (corbacserdar / Adobe Stock )

These primary results were compared with other sources including DNA from microbiomes from industrial and foraging populations, as well as wastewater and soil. This revealed to the researchers that the mediaeval microbiomes discovered in the latrines at Jerusalem and Riga held common characteristics. However, according to co-lead author, Susanna Sabin, while similar to the types of microbiomes found in modern hunter gatherer poop, and modern industrial microbiomes, the samples from Jerusalem and Riga were “different enough that they formed their own unique group.”

Tracking Changes In Human Gut Bacteria

What this study represents is an advanced method for analyzing human gut bacteria from different time periods. At this stage the scientists reported that they have yet to find a modern gut bacteria source that in anyway matches the microbial content found the in the mediaeval latrines. Speaking with Smithsonian, Dr Bos said the team of researchers will need “many more studies at other archaeological sites and time periods to fully understand how the microbiome changed in human groups over time.” But for now, the study is a big leap forward as a way of analyzing the gut bacteria DNA recovered from ancient latrines. The first results indicate that this analysis method is a promising way to study the diets and lifestyles of ancient people.

This investigation has confirmed Dr Mitchell’s primary suspicions. Specifically, the DNA remnants from “Treponema” bacteria, which are found in the guts of modern hunter-gatherers but not industrialized people, and “Bifidobacterium,” which are present in industrialized people but not hunter-gatherers, indicate what Dr Mitchell describes as “a dietary trade-off.”

How amazing to know that medieval gut bacteria from ancient poop can tell us so much about the past and also the health of humans today.

Top image: Toilet in Medieval Castle. Credit: Kondor83 / Adobe Stock

By Ashley Cowie

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 10th, 2020

October 10th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: