Saxo Grammaticus was a Danish historian whose writings were instrumental for the preservation of the ancient history of the Danes and their nations. Considered to be one of the major historical figures in Denmark, Saxo Grammaticus left an irreplaceable mark on Europe’s medieval history. With his writings he gave us an important glimpse into the very distant past of Denmark and Europe as a whole. And, what is more, his descriptions of legends and myths served as inspiration for some other literary greats!

What We Know About Saxo Grammaticus and His Work

The period of Danish medieval history in which Saxo Grammaticus lived is still – sadly and unjustly – obscure. And even though the work that this historian left behind him is immense and important, not much is known about his origins and early life. The Danish Chronica Jutensis (“The Jutland Chronicle”), written about two centuries after Saxo Grammaticus’ death, gives some evidence that this venerated medieval historian was born on the Danish core island of Sjælland (known commonly as Zealand). His exact year of birth is still unknown, but it is most likely that he was not born before the year 1150 AD, and that he died sometime around 1220 AD.

Representation of Saxo Grammaticus later in life, drawn by the Norwegian illustrator Louis Moe. ( Public Domain )

The name Saxo might sound a bit odd. In fact, it is a Latinized form of an attested Norse Germanic name Saxi (Saksi, Sachso), that is more than likely related to the Saxons and their name. At the time of Saxo Grammaticus’ life, it was a common name used in Denmark.

The actual surname of this historian is, however, unknown – Grammaticus is simply a “nickname” that he earned later in his life. It means “ the Learned ”. Whether or not this nickname was in use during his life is likewise unknown – the name Grammaticus appears first in the abovementioned Jutland Chronicle, written well after his death, and the later Zealand Chronicle ( Ældre Sjællandske Krønike ). In this latter work he is named as Saxo cognomine Longus (Saxo, nicknamed the Tall).

During Saxo’s life, Denmark was reaching its zenith – greatly expanding and becoming a powerful nation at its very height. This was achieved during the reign of King Valdemar I (Valdemar the Great), and solidified during the reign of his son, King Valdemar II. Saxo Grammaticus was a first-hand witness to the period of expansion and warfare with which it was achieved.

This is due to the fact that he was most likely a clerk and a secretary of the Archbishop of Lund, the famed warrior bishop Absalon, who himself led many of the Danish conquests. At the time, the Danes were in constant conflict with the ever-expanding Slavic tribes at their borders, who they called the Wends.

This led to a series of “Wendish Crusades”, which culminated with the conquest of the last and major Slavic fortress of Arkona on the island of Rügen, in 1168 AD. Bishop Absalon himself led the conquest and toppled the famed statue of the Slavic God Svantevit. Saxo Grammaticus could have accompanied him.

‘The Taking of Arkona in 1169, King Valdemar and Bishop Absalon’ by Laurits Tuxen. ( Public Domain )

A Soldier, a Writer, and a Historian All at Once

There are several pieces of evidence that tell us that Saxo might also have been a “soldier historian”, and that he went on these crusades to bear witness to the events which he wrote about. A certain nobleman from Denmark, Sven Aggesen, who also authored a less substantial History of Denmark, mentioned in his writings that Saxo Grammaticus – his contemporary – was also his “tent comrade”, indicating that the two spent time in soldierly service.

Saxo himself writes about this in his work, mentioning that he comes “from a warrior family” and that he is “committed to being a soldier”. He goes on to write that his lineage is that of warriors, and that he thus follows “the ancient right of hereditary [military] service”, since both his father and grandfather were in the service of King Valdemar I.

This, followed with some of his other writings, tells us that he was a learned man from a prominent family, and as such managed to rise in the ranks of the court. Evidence suggests that he was exceptionally well educated – most certainly outside of Denmark – and that he was fluent in Latin. This fact somewhat confirms that he was the son of a nobleman – that is how he would receive a foreign education, most likely in Paris.

His writing also reveals that he had the patronage of Absalon, the Archbishop of Lund whom we mentioned above. At the time Absalon was the second most powerful man in Denmark, besides the king – whom he advised. Further proof can be found in the will of Absalon: in it he mentioned his clerk Saxo, to whom he forgives a debt of two and a half marks of silver, and instructs him to return two borrowed books to the monastery of Sorø, (Sorø Abbey, the wealthiest monastery in medieval Denmark).

Eventually, Saxo Grammaticus was commissioned by either King Valdemar, or by Archbishop Absalon, to write a “heroic” history of the Danish people. In his work, Saxo says that he was “encouraged” to do so by Absalon. However, what is meant by the word “heroic” is somewhat different: Absalon certainly commissioned the work as a biased history of the Danes and a veritable propaganda piece that was sorely needed at the time of the greatest Danish expansion in history.

‘The Capture of the Wends’ by Wojciech Gerson. ( Public Domain )

As such, the work is heavily steeped in Christianity and its bias. Nevertheless, the end result made Saxo one of the most influential authors in the history of Denmark, and a very important source of information for all subsequent historians. That lengthy work was titled “Gesta Danorum” , and is by far the most ambitious literary achievement of medieval Denmark.

The “Gesta Danorum” Emerges

Saxo finished this work somewhat after 1208, and shortly before the Danish king managed to gain a foothold in Estonia – which is not included in the book. The work consists of sixteen books, making it quite a voluminous work, and it touches on both Danish history, and Scandinavian history in general. Throughout the books, Saxo touches upon themes and events from “prehistory” all the way to the 12th century.

Although mixing legends and myths with real historical events, the “Gesta Danorum” is nevertheless a crucial source of information – even by today’s standards. Writing of the times more recent to him, Saxo provided key information on the medieval nations and politics of the time. Nevertheless, he describes other nations from a biased point of view, and the book as a whole is heavily following the teachings of the Church, as was likely commanded by Absalon. Sadly, the archbishop died before “Gesta Danorum” was finished.

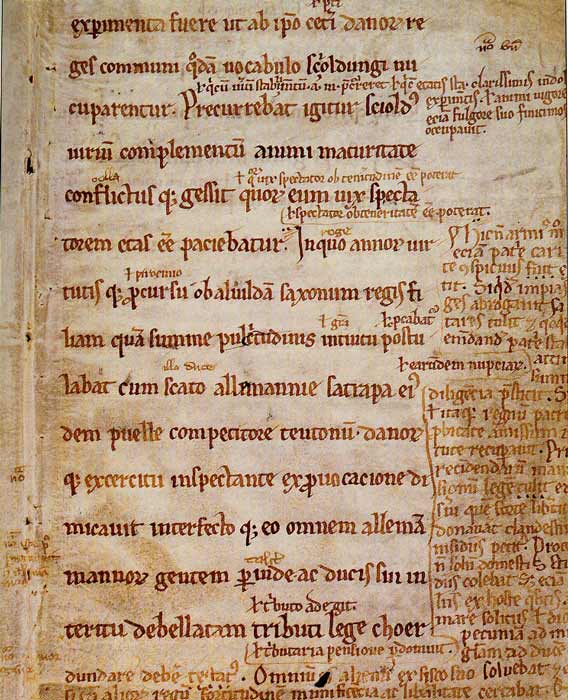

Page 1 of the Angers Fragment of the Gesta Danorum (Deeds of the Danes) manuscript by Saxo the Grammarian, located in the Royal Library of Copenhagen. ( Public Domain )

That Saxo Grammaticus was a “warrior historian” can be safely assumed after examining the book. Besides him mentioning that he comes from a “line of warriors”, Saxo pays a lot of attention to detail when writing about warfare and the crusades. He mentions King Cnut II as his favorite Danish King, which could be due to the fact that Cnut, in the early 1080’s, waged decisive offensive warfare against his neighbors, strongly supported by the Danish Church. Today he is Saint Canute.

Alas, due to the fact that Denmark was in a state of war throughout much of the early medieval period, Saxo’s work often deals with just warfare in general. It is these parts of the book that are most vivid, engaging, and detailed. In the 12th century, Denmark was continually suppressing its pagan neighbors – mainly the Slavs, the Estonians, and the Curonians. This was not due to religion – but due to money: the mentioned pagans were their main naval competitors. Judging by the detail with which these conflicts are described, it is safe to assume that Saxo was directly involved in them.

Since it was published, the “Gesta Danorum” has been heavily studied by historians all around the world, which has yielded many different interpretations. In Denmark, it was usually considered as their iconic national history and is widely regarded as a national “monument”. What is more, the work can be seen as a national history not only by the Danish people, but also by the whole of the Scandinavian world. German and Anglo Saxon scholars too can gain many insights from the book, especially the parts that deal with Scandinavian “prehistory”. As such, it is a key glimpse into that mythical, iconic Germanic lore and legend that is an indivisible part of the identity of all Germanic people.

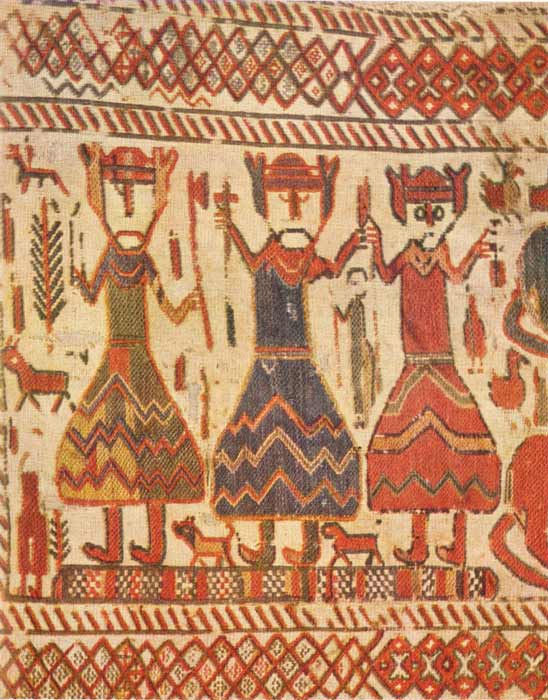

Odin, Thor and Freyr or three Christian kings on the 12th century Skog church tapestry. ( Public Domain )

But when actual historical fact is considered, “Gesta Danorum” is a valuable source of information in many other regards, especially medieval events. This book is a wealth of information about the Pomeranian Slavic tribes that dwelt for centuries in the larger part of what is today Germany. Directly bordering the Danes on the Jutland peninsula, they became their bitter and traditional enemies. Saxo’s work tells us a lot about their names, their rulers, and their pagan culture. In summary, “Gesta Danorum” is a good source of information for both cultural and political history of the region.

It is probable that Saxo Grammaticus, after his “military career”, became involved with the (at the time) Danish Lund Cathedral, where he wrote his work. The compiling of such an exhaustive book was certainly a task that took many years, and could have been written in Saxo’s senior years. Here it is important to note that “Gesta Danorum” is a prosimetrum work. This means that (in six of the first nine books) Saxo inserts poems. The poetry is meant to serve as a certain parallel to the old Danish heroic poetry, only written in the special Latin meters.

As for the prose in the book, which was written in Latin, the style that Saxo employs shares plenty of similarities with ancient writers such as Martianus Capella and Valerius Maximus. Still, Saxo’s style includes some much needed humor, compelling storytelling, and a good attention to details.

From Amleth to Hamlet – Shakespeare Was Inspired!

“Gesta Danorum” is unique in another aspect. It is the first work to include the story of a medieval Danish Prince – Amleth. Saxo devoted particular attention to this tale. And it seems that this very account served as major inspiration in the writing of Shakespeare’s iconic “Hamlet”!

The two tales share not just the name of the main character, but also the majority of the story elements. In that way, Saxo Grammaticus managed to inspire with his writings not just scholars and historians, but also the giant of play writing, Shakespeare – several centuries after “Gesta Danorum” was written.

‘Amblett’ in a 17th-century Danish manuscript illustration. ( Public Domain )

Since the late 1980’s, and particularly during the 1990’s, there has been a unique revitalization in studies of Saxo Grammaticus and his work. This resurgence came as the result of renewed studies of Western medieval scholarship, which was in a way placed under major scrutinization. New themes, new concerns, and questions arose amongst the leading historians in Europe, and Saxo’s work was once more a valuable source of information. In particular, scholars praised his attention to details and just how intricate his elaborations were for the time in which they were written.

And even though his work “marched in tune” with the developments of the time, and it is – as such – heavily biased, it is nevertheless a solid and factual national history. And it is one that not many medieval nations could boast at the time.

For the rising power that Denmark was at the time, a compelling national history was a defining “cherry on top of the cake”. And the writing of such a monumental work had to be placed into the hands of a skilled writer and scholar – who also happened to be a seasoned warrior as well. And Saxo Grammaticus was all of that – and more!

Top Image: Saxo Grammaticus was a medieval Danish “warrior historian.” Source: diter / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Bailey, C. 2002. Saxo Grammaticus: History and the Rise of National Identity in Medieval Denmark. Eastern Illinois University.

Friis-Jensen, K. 1981. Saxo Grammaticus: A Medieval Author Between Norse and Latin Culture. Museum Tusculanum Press.

Muceniecks, A. 2017. Saxo Grammaticus: Hierocratical Conceptions and Danish Hegemony in the Thirteenth Century. Arc Humanities Press.

Raudkivi, P. and Andersen, T. 2007. From Saxo Grammaticus to Friedrich Suhm: Danish Views on Medieval Estonian History. Tallinn University.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 14th, 2021

April 14th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: