Opportunism, ambition, intrigues – these were aspects that were always present at the courts of great empires. Rulers rose to power following these rules of the game, and they were often the reasons for their undoing too. Romanos IV Diogenes was the Byzantine emperor from 1068 to 1071 AD. He strove to be a respected and capable leader. However, his life and his reign were constantly hampered by outside forces, causing his brief rule to come to a sad conclusion. His fate, and his unfair deposition, would come to stain the Byzantine reputation and would haunt it for generations to follow. What follows is the story of Romanos IV Diogenes, who gave his best shot at leading a vast empire. But was it enough?

Destined for Greatness: The Early Life Of Romanos IV Diogenes

Even from his birth, Romanos IV Diogenes was destined for greatness. He was born around the year 1030 AD, as a son of the prominent Byzantine general, Constantine Diogenes. This man was a major strategos (general) in service of the then Emperor Basil II Porphyrogenitus, the Bulgar Slayer .

When Basil II reconquered the Balkan provinces , Constantine Diogenes was placed as the governor of the theme of Syrmia, a place of power and prominence. The family of Diogenes was a powerful Byzantine Greek lineage originating from Cappadocia, and one of the major families of the “military nobility,” which was a central player in the numerous conflicts that shook the Byzantine Empire during the 11th century when the civil and military nobility clashed against one another.

In his early years Romanos IV Diogenes was the duke of Serdica (modern-day Sophia, Bulgaria) and he likely visited this famous church, Boyana Church, more than once. (Interact-Bulgaria / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Romanos IV Diogenes rose through the ranks and gained prominence very early on in his youth. He was often described as very courageous and ambitious, if not a bit rash and impetuous at times. As was common for the members of his family, Romanos served in the military with prominence, mostly in the Balkans, at the Danubian frontier. By 1067, he was installed as the doux, or duke, of Serdica, where a new province was reorganized and needed a capable leader.

But all that would soon change, when the young and ambitious Romanos was easily dragged into an affair at the Byzantine royal court. When Emperor Constantine X Doukas died in 1067, his sons were still minors. The throne thus passed into the hands of Constantine’s widow, Eudokia Makrembolitissa, who could reign as the de-facto empress until her sons came of age. She also swore that she would never marry again.

At the time Romanos IV Diogenes conspired with Princess Theodora and attempted to seek the aid of Hungary to usurp the throne from the minor sons of late emperor Constantine. His attempts failed, and he was soon imprisoned by Romanos III Argyros, and sentenced to death for this conspiracy. However, the empress Eudokia recognized the potential that Romanos had.

At the time Byzantine Empire was under a lot of pressure. The Seljuk Turks constantly raided the empire’s edges, and the Byzantine army could not effectively respond, due to the lack of development in the years prior. Eudokia knew that she alone could not remedy the situation, and that a new emperor was needed, and it had to be a seasoned military veteran.

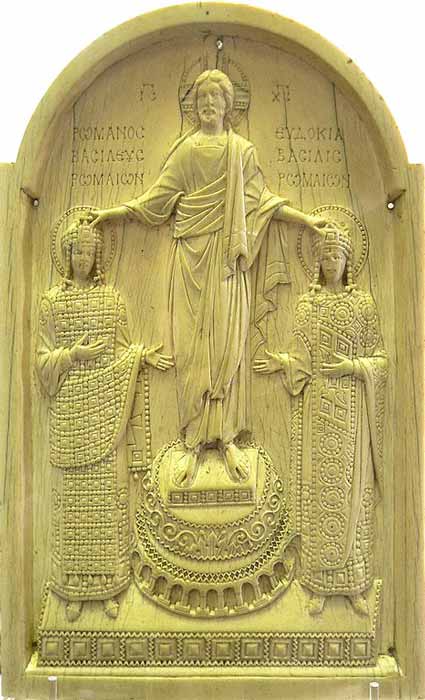

Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa and Romanos IV Diogenes are suddenly married and he goes from prison to the imperial throne of the Byzantine Empire, almost overnight! Note: Until 1926 the pair pictured were as indicated here, but this has since been revised. (Photographe: Clio20 / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Romanos IV Diogenes: From Prison To The Byzantine Throne

Romanos also enjoyed immense popularity. One could say that he was a sort of celebrity at the time, and some sources describe him as particularly handsome and charming. Moreover, he had a lot of military experience as a general and was the ideal choice for emperor in more ways than one.

Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa and her closest advisors saw this immediately and chose Romanos IV Diogenes to be their new leader. Some sources say that the empress saw even more than that and that she became infatuated by Romanos and desired him. Thus, the death sentence against Romanos was never passed.

In an odd turn of events, this young and energetic noble narrowly avoided death and immediately jumped to the position of emperor of the Byzantine Empire. The vows that Eudokia gave not to marry were promptly annulled by the Patriarch of Constantinople , and the two were married on January 1st, 1068 AD.

It became clear in contemporary sources that Romanos IV Diogenes was quickly accepted by almost everyone at the court. He was instructed on his obligations as emperor, and he understood the reasons for his pardon. He also accepted this position with the zeal and ambition that is so iconic for young noblemen. It was his energetic approach that Eudokia knew was necessary for the Byzantine throne.

And while Romanos was accepted by most, he still faced enemies. This was particularly true of the brother of the late Emperor Constantine, John Doukas , who saw the arrival of Romanos as a great threat to the powerful Doukas dynasty, and the minor sons of Eudokia. He held a big grudge against Romanos and constantly plotted to bring his rule to an end.

One of the first and foremost obligations that Romanos had as the new emperor was to address the disastrous state of the Byzantine eastern frontiers. For almost a decade it was left unattended due to the negligence of Emperor Constantine X, and now the Seljuk Turks became a major threat, constantly raiding the territory.

At once, Romanos proved his shrewdness and an honest desire to combat this threat. The decades of civil war in the empire and the dominance of the civil aristocracy had devastated the defensive capabilities of the Byzantines. What Romanos IV Diogenes now had at his disposal was a meager mercenary force of Slavs, Franks, and Bulgars, who were poorly disciplined and stubborn, though they were fierce warriors.

That is when Romanos made a bold and shrewd decision: he ordered the renewal of the great tagmata (τάγματα) army that was completely neglected in generations past. Tagmas were elite heavy cavalry units, mobile and highly skilled, and maintained on a permanent basis. These units were always considered as a political power: whoever controlled them held all the power. That is why this move by Romanos IV Diogenes was misunderstood by his opponents. They didn’t see it as an honest attempt to defend the empire’s borders, but as his attempt to use military power to limit their influence and their power.

Romanos IV Diogenes’s biggest enemy beyond his internal foes were the Seljuk Turks and this is their leader, Alp Arslan (1029-1072 AD), ascending the throne in Herat, Afghanistan. (Hafiz-i Abru / Public domain )

Romanos IV Diogenes’s Greatest Enemies Were The Seljuks

During his relatively short reign, Romanos IV Diogenes undertook four campaigns against the Seljuk Turks. The first was made in 1068 AD. After just three months he managed to assemble a force of roughly 35,000 men and marched them against the Seljuks and their Arab allies from Syrian Aleppo. These two forces had been raiding and devastating Armenia, Cilicia, Cappadocia, and Georgia.

Romanos marched south with his army and eventually managed to inflict two major defeats against the Turks in the battles of Sebaste and Ieropolis. However, neither of these victories were enough to end the Seljuk threat, as they rapidly fled and avoided a head on collision with the Byzantines. The Turkish cavalry moved so rapidly across the country that Romanos could not possibly react in time. Thus, the Seljuks raided Neocaesarea and Amorium before moving on. With the onset of winter, Romanos IV Diogenes returned to Alexandretta, and eventually to Constantinople.

In April 1069 AD, Romanos launched another campaign. His new attempt saw him marching towards Caesarea where the first clash with the Seljuks occurred. As the Byzantine army was raising their camp, they were surprised by an attack from the Turks. However, Romanos’ skilled command helped them to gain a victory against all odds.

Still, their rapid movements did not give Romanos the chance to strike a decisive victory he yearned for, leaving him to waste his efforts in frustration. Eventually he caught up with the Seljuks at Tarsus, the capital of Cilicia, where his armies won decisively. The Seljuks were forced to flee to Aleppo, and Romanos made a peace with the Turkish sultan Alp Arslan. Nevertheless, he did not manage to defeat the Seljuks, and this caused some discontent in Constantinople. Even though peace was made, a major victory was not.

Romanos wasted most of his campaign chasing the fast-moving Seljuks. A contemporary account of one of his opponents at the time who was present at the campaign perfectly sums it up: “ Romanos didn’t know where he was marching to, or what was he to do.”

The third campaign, in 1070 AD, was not led by Romanos. The increasing political intrigues at the court forced him to remain put in Constantinople. He had to face the events in other parts of the empire, and to focus on bringing new reforms that would further contribute to the stabilization of the empire. Some of the reforms he brought were especially disliked by his political opponents and the members of the nobility, and eventually the common folk.

All the reforms he made were for the good of the empire. First he reduced unnecessary court expenses, lavish ceremonies, and decoration of the capital. These funds had to be shifted to more important expenses. Public salaries of court nobles were also reduced, along with the overall profits of prominent traders in Constantinople. Romanos focused much of his energy and budget on improving the Byzantine army. This made him unpopular with provincial governors, whose power became increasingly less independent.

The Battle of Manzikert, fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, was a decisive defeat for the Byzantine army and ended in the capture of Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes. (O.Mustafin / CC0 1.0 )

Romanos: Disliked By His Mercenary Troops And The Peasants

Moreover, Romanos was disliked by his mercenary troops, as he required strict discipline. Lastly, Romanos was, quite unjustly, disliked by the common folk. He could not ease the issues of peasantry in the provinces and did not provide the citizens with the annual hippodrome games. Thus, although he made reforms that would greatly benefit the empire, he gained the animosity of everyone in the process. Of course, this would be used by his biggest opponent, John Doukas.

The following year, 1071, would prove to be decisive in many ways for both Romanos and the Byzantine Empire. In the spring he once more marched his armies against the Seljuk Turks. At the head of a strong army, he marched across Theodosiopolis and reached Manzikert, retaking it with ease. However, the main body of the Seljuk army was fast approaching the town, and a new clash soon emerged, known today as the Battle of Manzikert.

This battle was defined by the betrayal of Andronikos Doukas, the son of Romanos’ main opponent, John Doukas. In a decisive moment Andronikos exploited the confusion in Byzantine ranks and fled with 30,000 reserve troops, leaving Romanos’ retreat unprotected.

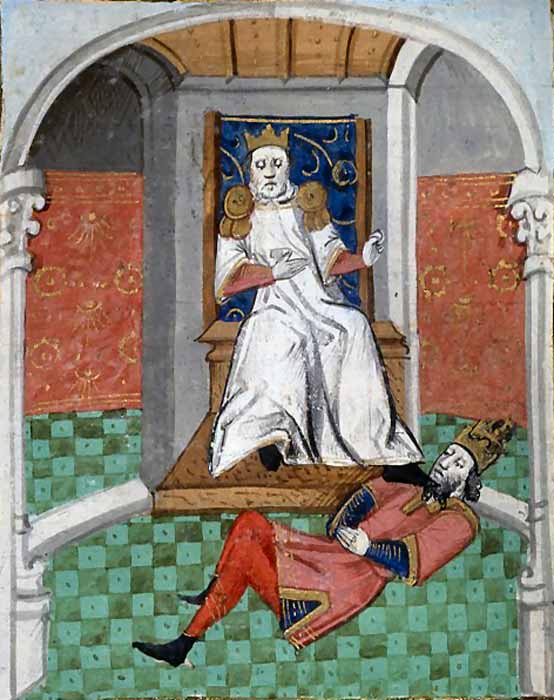

The battle was a major Seljuk victory, and the downfall of Romanos IV Diogenes. The latter was wounded and captured in the battle and brought as a captive before the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan. A legendary meeting then ensued: Alp Arslan performed a ritual of submission against Romanos, by placing his foot on the latter’s neck. However, he immediately helped him up and treated him with utmost respect and courtesy, caring for him for eight days. The legend describes their conversation as such:

[Alp Arslan]: “What would you have done if I was brought before you as captive?”

[Romanos IV Diogenes]: “Perhaps I would kill you, or parade you through the streets of Constantinople.”

[Alp Arslan]: “Yet my punishment for you will be much crueler: I shall forgive you and set you free.”

The two leaders once more came to a peace agreement, although Romanos was captured in battle. The Byzantines had to pay a hefty ransom and an annual tribute, and Romanos was set free.

However, it was of no use to him. During the events at Manzikert, immediately after Romanos’ capture, the nobility at the court of Constantinople, headed by John Doukas, decided to exploit the ongoing situation and organized a coup d’état that placed a new emperor on the throne, the son of late Constantine X, young Michael VII Doukas.

Alp Arslan, leader of the Seljuk Turks, with his foot on Romanos IV Diogenes’ throat. (Boccace, De Casibus / Public domain )

Romanos: A Courageous And Upright Man In All Ways!

Romanos IV Diogenes was not about to go out undefeated though and assembled a small force to retake his throne. He was, however, defeated before he reached the capital, but was guaranteed safety and a safe return to the capital.

This guarantee was promptly ignored by the members of the Doukas family, and Romanos was betrayed once again, when he was captured on his way back to Constantinople, blinded with red hot iron, and exiled to a monastery on the remote island of Prote in the Sea of Marmara. He died there soon after from the wounds of the blinding, in the summer of 1072, when he was just 42 years old.

This ended one of the most promising Byzantine imperial reigns of this period. Romanos was an ambitious and energetic leader who knew what was important for the survival of the empire. However, justice, reason, and reasonable expenditure are not popular with the corrupt nobility and greedy officials.

Every reform and every step that Romanos IV Diogenes took in his reign was logical and sound yet despised by the court. His betrayal at Manzikert was a cowardly move by the Doukas family, and directly contributed to the Turkification of Anatolia and the irrecoverable loss of Byzantine power in the region.

Moreover, the deposing and blinding of Romanos was one of the biggest tragedies in Byzantine history. The famed English historian John Norwich summed it up perfectly, saying that the greedy enemies of Romanos IV Diogenes “martyred a courageous and upright man.”

Top image: Romanos IV Diogenes ruled towards the end of the Byzantine Empire. Here a Byzantine mosaic. Source: Xavier Allard / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Basan, O. 2010. The Great Seljuqs: A History. Routledge.

Goodyear, M. 2018. Romanos IV Diogenes. World History Encyclopedia. [Online] Available at:

https://www.ancient.eu/Romanos_IV_Diogenes/

McGeer, E. and Nesbitt, J. 2019. Byzantium in the Time of Troubles: The Continuation of the Chronicle of John Skylitzes (1057-1079). BRILL.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 11th, 2021

March 11th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: