There are very few texts that survive from early medieval Wales, an era spanning the moment when the Romans left Wales until the Normans arrived. This is one of the reasons that historians have generally assumed that the peoples of early medieval Wales were uncivilized barbarians. In the absence of Roman literary culture, some thought Welsh society devolved back to a pre-literate state, believing that literature and learning left its shores with the Romans. There are however clues to the fact that this was not the case. The inscriptions on commemorative standing stones are important pieces of evidence for what Welsh society was like during this era.

There are over 50 commemorative stones that survive from the 5th to the 9th centuries in Wales, some inscribed with memorials for the dead and others proclaiming great victories in battle. These stones are a unique feature of early medieval Wales, because of the way they combine the Irish practice of putting up commemorative standing stones with the Roman tradition of public inscription in Latin. Combined with other evidence, these stones tell us of the important place that Roman culture and tradition held in medieval Welsh society and how they co-existed with the Celtic and Brittonic elements of Welsh culture.

Roman Civitas and the Welsh Kingdoms in Medieval Wales

The Romans settled vast areas of Britain, including Wales, but the majority of their influence was contained in the southeastern and northeastern parts of Wales, while they also maintained a more superficial presence in the west. It is interesting then, that most of the commemorative stones from the period immediately following Roman occupation, the 5th and 6th centuries, have been found in northwestern and southwestern Wales. In other areas of Roman-occupied Europe, similar stone inscriptions have been found alongside other evidence of continued Romano-Christian lifestyle beyond Imperial occupation.

In the western parts of Wales, evidence of Roman lifestyle is decidedly lacking. Even during the Roman occupation, there is no evidence of any civitas (Roman civil administration) in western Wales, no Roman villas uncovered in the area and, besides a major military harbor, only a handful of late Roman forts and auxiliary garrisons. The influence of Irish settlers seems to have been more prominent than that of the Romans, particularly in southwestern Wales which received an influx of Irish settlers in the late Roman period, and many inscriptions written in Irish ogham have been found on standing stones in Wales. Nevertheless, by far the greater number of inscriptions found are in Latin and use the distinctive Roman Capitals script, which is instantly recognizable as Roman.

The Welsh clearly desired to set themselves apart from other contemporary cultures that used symbolic scripts on commemorative stones – the Irish ogham and the Anglo-Saxon runes – and emphasize their Romanitas (“Roman-ness”), not only by the choice of script but also the language of the inscriptions. Despite being a Brittonic culture, the aristocrats of early medieval Wales who erected these commemorative stones chose to use the language of the Romans. Many even Romanized their own names by changing the ending of a Brittonic name to a Latin one – for example, “Brohomagli”, “Conbarrus”, and “Devorigi”.

Many of the inscriptions also claim some kind of social status for the subject of commemoration in distinctly Romanized terms. Most British memorial inscriptions from the early medieval period claim status for the subject only by virtue of the subject’s father, but the Latin inscriptions from Wales use a variety of titles and status markers including magistrati (magistrate), medici (healer), and protictoris (protector). Some even make clear statements of Romanitas by characterizing the subject of memorial as cives (the Roman term for “citizen”) or latio (someone from Latium/Rome).

More than any other inscriptions found in Britain from the early medieval period, the Welsh inscriptions show an eagerness to express the Latinity and Romanitas of their subjects. The big question is why. Why, in one of the least Romanized areas of Britain, were the inhabitants so keen to emphasize their connections to the Roman Empire after its people had left their shores? There are several possible explanations, but only one that historians agree on almost unanimously.

The withdrawal of the Roman Empire from Wales, and the rest of Britain, had a huge impact in the area as Roman structures of government and power steadily collapsed in medieval Wales. ( serpeblu / Adobe Stock)

After the Fall of the Romans in Wales – the “Hiatus”

The chaos and upheaval caused by the withdrawal of the Roman Empire from Britain and the subsequent Anglo-Saxon invasion had ripple effects throughout Britain. Aside from the wars and bloodshed, as well as major economic changes, many people all across the isle of Britain were displaced and forced to resettle elsewhere. Gildas, for example, in his On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain , mentions that many people were uprooted by the arrival of the Saxons and there is evidence that some of these settled in Wales. This change in the demographics of Welsh populations has been suggested as a possible reason for the sudden Romanization of northwestern and southwestern Wales in the 5th century, especially if these people had relocated from more heavily Romanized areas.

It is also possible that in response to the collapse of economic stability brought by Imperial rule, the British kingdoms sought to maintain trade and diplomatic connections with the Empire. There is some archaeological evidence of trade between the Welsh kingdoms and the Empire, specifically in the kingdom of Gwynedd, and references to the consul Justinus in some of the Welsh stone inscriptions seems to support the theory that the emphasis on Roman connections was economically motivated. There is more convincing evidence however, that the desire for Romanitas was not an economic strategy, but rather a political one.

The centuries following the Roman era have been characterized as a “hiatus” in which Roman structures of government and power steadily collapsed and were replaced by various models of leadership that were simultaneously in effect. The “clientage” and militarism of Anglo-Saxon kingship and the Irish model of ruiri or “great kings” both seem to have influenced how rulership in the early medieval Welsh kingdoms was structured. Evidence from the standing stone inscriptions indicates that Welsh elites asserted power by appealing to Brittonic tribal traditions and other non-Roman power structures: the Brittonic epithets Monedorigis (“king of the mountain”) and Tovsaci (“the prince/leader”) both appear on inscriptions from northwestern Wales.

The evidence in Gildas’ work of how rulership operated in post-Roman Wales appears to confirm that Britons employed a similar model of kingship to their enemies, the Anglo-Saxons, based on military prowess and a system of vassal kings pledging allegiance to an over-king. There are further clues in Gildas’ writing though, that suggest the power structures of the Welsh kingdoms were more complex and retained elements of Roman ideas about legitimate power and that political influence was still tied symbolically to the prestige and authority of the Empire.

At the ancient location of a Roman legionary fortress, near Newport in Wales, visitors can view the remains of the Caerleon Roman amphitheater (seen here), Roman baths and barracks, left behind in medieval Wales when the Romans left the area. ( Stephen Davies / Adobe Stock)

Kings, Tyrants, and the Legality of Rule in Early Medieval Wales

Gildas lived in a time of momentous change in the British political and cultural landscapes, and his work is one of very few surviving writings we have that give a British perspective of these historic events. Gildas himself seems to have been a Welshman, or at least we know he received his education in a Welsh monastery, and was an aristocrat by birth. The monk, who would later become a saint, belonged to a sector of British society which was a curious hybrid of Roman and British cultures – known by modern scholars as the Romanized elites. In his writing, we can see evidence of how this elite strata of Welsh society had been Romanized in their ways of thinking and prized Roman ideals and morality above all.

To Gildas, the Welsh kings of his time are closer to tyrants than kings and he denounced their un-Christian and immoral ways:

“Kings Britain has, but they are as her tyrants: she has judges, but they are ungodly men: engaged in frequent plunder and disturbance, but of harmless men: avenging and defending, yea for the benefit of criminals and robbers… They make wars, but the wars they undertake are civil and unjust ones.”

Gildas does not seem to have believed these kings were tyrants because they usurped the thrones they sat upon, but rather because their corrupt morality makes them, in essence, “un-Roman” and Roman-ness is what Gildas believes constitutes a truly legitimate leader. His description of Ambrosius Aurelianus reveals the Roman ideologies that underlie Gildas’ lamentations, describing the warrior as “a man of unassuming character, who, alone of the Roman race chanced to survive in the shock of such a storm” and bemoaning that his descendants have “greatly degenerated from their ancestral nobleness.” Obviously Ambrosius Aurelianus was not the only individual of Roman blood to remain on the island of Britain after the Romans left, but what Gildas is really saying is that those Britons of Roman descent have lost their Romanitas and as a result, Britain has come to ruin.

Looking at the inscriptions on the early medieval commemorative stones from Wales, it would seem Gildas was not alone in yearning for the “good old days” of Roman moral integrity and nobility. Many inscriptions attempted to claim Romanitas for their subject in terms of moral character, not just through their title or descent: the commemorated were often described as good Christians, as beatus (“blessed”) or sancta (“holy”), and one man, Bivatigirn, was characterized as “an example to all citizens and relatives both in character, morality and wisdom.” Inscriptions showcasing Roman aspects of their subject’s character may be evidence of a process in which a new class of Brittonic elites attempted to assert the legitimacy of their authority over a Romanized population by appealing to Romanized ideals.

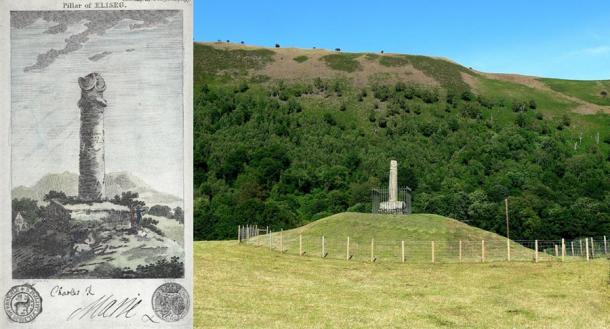

Eliseg’s pillar, which includes a Latin inscription, is believed to have been created in the 9th century. (Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Romanitas as Propaganda in Medieval Wales

The process of the ruling class using Romanitas to claim legitimacy seems to have continued past the post-Roman era in Wales and well into the Middle Ages. The best evidence we have of this continued Roman influence in Wales comes from the most famous of the Welsh commemorative stones: The Pillar of Eliseg. The Pillar is a 9th century inscription on a piece of stone reused from a much earlier monument, made for the king of Powys, Cyngen, in northeastern Wales to commemorate the victories of his great-grandfather, Elise, against the English. The inscription was in Latin but is unfortunately now illegible, although the text survives in a partial transcription made in the 17th century.

Aside from proclaiming military victories, the Pillar of Eliseg is primarily a genealogy of the royal family of Powys and is in fact the earliest surviving genealogy we have from medieval Wales. Genealogies were important documents in many medieval British societies, serving as statements of qualification for rulership and establishing the right of an individual to rule. Genealogy had also been important in Roman thought when determining the right to rule and while Celtic genealogies often traced ancestry back to a deity, Roman genealogies emphasized connections to great rulers of the past.

Left: 1809 engraving of the Pillar of Eliseg located in Denbighshire in Wales. ( Public domain ) Right: Modern-day view of the same monument.(Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Pillar of Eliseg: Remnant of “Roman-ness” in Early Medieval Wales

The Pillar of Eliseg does just that, tracing the ancestry of Cyngen and his family’s dynasty back to Magnus Maximus , “king” of Roman Britain. It was determined by Welsh scholars sometime in the early Middle Ages – possibly around Gildas’ time in the 6th century or even earlier – that Roman Britain ended with Maximus’ reign in 388 AD and therefore he was seen as the link between Roman Britain and an “independent” Britain. Interestingly, even though Maximus was in fact a usurper and unequivocally labelled a tyrant by Gildas, he came to represent the gateway to the continuance of Roman power and the embodiment of Romanitas. As such, his name featured as the apical ancestor in many genealogies of Welsh ruling dynasties in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Essentially, these genealogies were a form of medieval propaganda, using Maximus’ name and all the weight of history and legend it carried to represent the legitimacy of Cyngen’s claim to authority. The Pillar of Eliseg was very clearly meant to act as a piece of propaganda, not only in the contents of the inscription but its location was also particularly significant. The choice to situate the Pillar in front of a Bronze Age burial cairn, heavy with ancestral and spiritual associations, was consciously made, as was the choice of location in the Vale of Llangollen along the main corridor through the valley.

The Vale of Llangollen was the place where nine major roads through the region converged, and this made it a regional communications and socio-political hub, as well as a crucial corridor in terms of military, commercial and political strategy. It was also situated on frontier lands with fluid borders that were heavily contested by several kingdoms, including the powerful Mercia, and the Pillar’s strategic location allows views of both Offa’s Dyke and Wat’s Dyke on Mercia’s borders. Placed deliberately in such a location, the Pillar of Eliseg makes a powerful statement about the legitimacy of the authority the ruler of Powys holds over those lands and all who pass through them. The basis of that claim is two-fold: the military prowess demonstrated by Cyngen’s ancestor, which grants him legitimacy under Brittonic tribal models of rulership, and the ancestral link to Maximus, which grants him Romanitas.

There are many important things we can learn from studying the Pillar of Eliseg and the many earlier inscriptions that stand in stone all across the landscape of Wales, but perhaps one of the most important lessons is that we should not be too quick to make judgments about ancient societies without first closely examining the evidence. The withdrawal of the Roman Empire did not signify an end to culture and literacy in Wales, nor the descent into darkness and chaos that Gildas would have us believe. Romanitas continued to be a vital part of Welsh society for hundreds of years after the Romans left Britain’s shores. In fact, Roman ideals of authority and leadership laid the foundation of the Welsh kingdoms that would take the place of Imperial rule.

Top image: The Pillar of Eliseg is just one monument that bears witness to the Romanitas of early medieval Wales. Source: Public domain

By Meagan Dickerson

References

Chiu, H. 2006. “The Political Function of ‘Early Christian’ Inscriptions in Wales” in Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association 2.

Dumville, D. N. 1990. Histories and pseudo-histories of the insular middle ages . Variorum.

Guy, B. 2018. “Constantine, Helena, Maximus: on the appropriation of Roman history in medieval Wales, c. 800–1250” in Journal of Medieval History 44, no. 4.

Murrieta-Flores, P. and Williams, H. 2017. “Placing the Pillar of Eliseg: movement, visibility and memory in the early medieval landscape” in Medieval Archaeology 61, no. 1.

Sims-Williams, P. 1998. “The uses of writing in early medieval Wales” in Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies , ed. Huw Pryce. Cambridge University Press.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 4th, 2021

December 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: