Harsha was an Indian ruler who lived during the 7th century AD. He was a member of the Vardhana Dynasty, one of the regional powers that emerged in northern India following the collapse of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century AD. During his four decades on the throne, Harsha greatly expanded the territory of the Vardhana Dynasty. At the height of his power, Harsha was in control of much of northern and northwestern India. His attempt to expand into the south of India, however, was less successful, as he was defeated by the Chalukyas. This defeat marked the end of the Vardhana Dynasty, as he died childless and his throne was usurped.

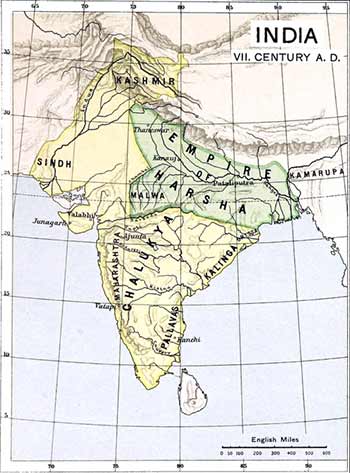

Map of India in the 7th century, showing the vast territory of the Empire of Harsha. ( Public domain )

Succeeding the Guptas: Becoming Emperor Harsha Vardhana

Much of the information we have of Harsha, known also as Harshavardhana, comes from the Harshacharita (meaning “Deeds of Harsha”), a biography of the ruler written in Sanskrit by Banabhatta, a poet who lived at the court of Harsha.

According to E. B. Cowell and F. W. Thomas, who published an English translation of the Harshacharita in 1897, this work “appears to have been almost forgotten in India.” Although Harsha was a formidable ruler, he seems to have been not significant enough to be remembered. This might not be overly surprising if one considers the situation in India at that point of time.

Harsha belonged to the Vardhana Dynasty, known also as the Pushyabhuti Dynasty, one of the regional powers that succeeded the Gupta Empire. The Gupta are believed to have originally been a wealthy family from either Magadha or Prayaga (today the city of Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, northern India). Towards the end of the 3rd century AD, the family accumulated enough power to become the rulers of Magadha. The first famous Gupta ruler was Chandragupta I, who came to power in around 320 AD. Although Chandragupta was the third Gupta king, he is often credited with the founding of the dynasty.

The Gupta Empire prospered between the 4th and the first half of the 5th centuries AD. To the east, a number of small kingdoms had been absorbed by the Gupta Empire , whereas in the west, the entire Indus Valley region had fallen under Gupta control. In the north, Gupta rule stretched all the way to the Himalayas, inclusive of Nepal, whilst in the south, the Guptas are said to have advanced all the way to the lands of the Pallavas. Additionally, in some of the more remote areas, defeated rulers were reinstated by the Guptas, thereby turning them into tributary states.

Around the middle of the 5th century AD, the Guptas were attacked by the Hunas, a group of nomadic tribes from Central Asia who entered the Indian subcontinent via the Khyber Pass. Although the Guptas managed to repulse the nomads’ first invasion, the Hunas continued their attacks on the Guptas in the decades that followed. By the first half of the 6th century AD, however, a coalition of Indian princes defeated the Hunas, who were led by Mihirakula, and succeeded in driving them out of India.

Nevertheless, the continuous attacks of the Hunas weakened the power of the Guptas, and, consequently led to the rise of successor dynasties in the 6th century AD. These post-Gupta dynasties included the Late Guptas, the Maukharis, and the Vardhanas. Thus, Harsha was only one of several kings vying for power in northern India after the fall of the Gupta Empire. This may have contributed to the Harshacharita being almost forgotten by the end of the 19th century.

Little remains from the rule of Harsha, although we can see his profile on this coin from the 7th century. (Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Harsha’s Tumultuous Rise to Power

According to the Harshacharita, Harsha was the son of Prabhakara, known also as Prabhakaravardhana, the ruler of the Vardhana Dynasty and King of Thanesar around the time of the Gupta Empire’s collapse. Harsha’s mother was Yasovati, Prabhakara’s chief wife, and he had two siblings, an elder brother by the name of Rajya and a sister named Rajyashri. Prabhakara died whilst his heir, Rajya, was away on a campaign against the Hunas. Harsha summoned his brother Rajya who returned immediately. Overwhelmed by grief, Rajya decided to become an ascetic, leaving the throne to Harsha.

Around the same time, however, news arrived regarding their sister, Rajyashri. The princess had married Grahavarman, a member of the Maukhari Dynasty, the ruling family at Kannauj. This marriage strengthened the alliance between the two dynasties, which did not sit too well with the Gaudas, who controlled Bengal. Therefore, the Gaudas allied themselves with the Malwas, whose kingdom was in central India.

The Gaudas and Malwas launched an attack on the Maukharis, killing Grahavarman and throwing Rajyashri into prison. When Rajya received this terrible news, he assembled an army and marched against his enemies. This military expedition was not only meant to rescue Rajyashri, but also to avenge the death of her husband. Whilst Rajya was away on this campaign, Harsha was left to run the kingdom as vice regent. Although Rajya was able to defeat his enemies easily, he was treacherously assassinated by the King of Gauda.

As a result of Rajya’s death, Harsha became the new ruler of the Vardhana Dynasty. As the new king, Harsha sent his cousin Bhandi after his brother’s killers, while he himself set off himself to rescue his sister. According to the Harshacharita, Harsha was able to find his sister just as she was about to mount her funeral pyre, thanks to the help of a Buddhist mendicant. Harsha rescued his sister and made a vow that they would both assume the garb of Buddhist mendicants once the King of Gauda was defeated.

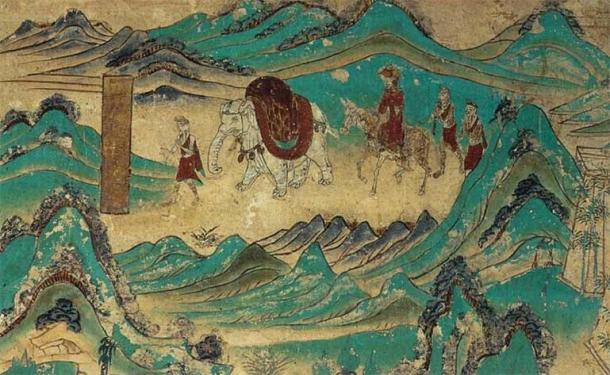

Xuanzang famously travelled to India to find answers to the discrepancies and contradictions he discovered in Buddhist doctrine. There he visited Harsha’s palace and included a description of him in his writing. ( Public domain )

Harsha’s Inclination to Buddhism and the Travels of Xuanzang in India

It is not entirely clear, however, if Harsha did become a Buddhist. For instance, the Harshacharita makes note of the favor shown by Harsha towards Buddhism and its teachings. Nevertheless, Harsha is also said to have been tolerant towards his Hindu subjects. Harsha’s inclination towards Buddhism is also mentioned by Xuanzang, the famous Buddhist monk who travelled from China to India and brought hundreds of Buddhist scriptures back to his native land.

Xuanzang was born in 602 AD, when China was under the rule of the short-lived Sui Dynasty . Although Xuanzang received a classical Confucian education as a youth, he became interested in Buddhist teachings, thanks to his older brother’s influence. Consequently, Xuanzang converted to Buddhism, and eventually became a monk.

The Sui Dynasty fell in 618 AD, and was replaced by the Tang Dynasty . As a result of the ensuing political turmoil in the country, Xuanzang and his brother fled from their home in Henan to Chang’an, the Tang capital, and thence to Sichuan. There, Xuanzang continued his study of Buddhist doctrine. He soon realized, however, that there were many discrepancies and contradictions in the texts. The young monk consulted his Chinese masters, but they too were unable to address his doubts. These unresolved questions troubled Xuanzang, who made the decision to travel to the birthplace of Buddhism, India, where he hoped to find the answers to his questions.

Unfortunately for Xuanzang, at that point of time, the Chinese were at war with the Gokturks, which caused the emperor to issue a travel ban in China. This meant that Xuanzang was not able to obtain a travel permit for his journey to India. Although the young monk respected authority, he felt that his mission was much more important, since it was only by going to India that the problems found within the Chinese Buddhist texts could be resolved. Therefore, in 629 AD, Xuanzang left China under the cover of darkness, and essentially became a fugitive. In the years that followed, Xuanzang faced numerous challenges on his journey to India, finally arriving at his destination in 633 AD.

In India, Xuanzang travelled as a pilgrim to all the sacred sites connected with the life of the Buddha. Additionally, he made trips along the eastern and western coasts of the country. For the most part of his time in India, however, Xuanzang was based at the Nalanda monastery. This was the foremost center of Buddhist scholarship at the time, and Xuanzang used his time there to perfect his knowledge of Sanskrit, Buddhist philosophy, and Indian thought.

Thanks to Harsha’s patronage that Xuanzang was able to journey back to China from India in 643 AD. ( Public domain )

The Friendship Between Xuanzang and Harsha

In time, Xuanzang’s reputation as a Buddhist scholar spread throughout India, and the monk attracted the attention of none other than Harsha himself. Incidentally, by this time, Harsha had become a mighty king, and ruled a large portion of northern India. Harsha’s rule, however, was indirect, as he did not annex the territories of the kings he had defeated. Instead, he left them on their thrones, collecting tribute and homage from them.

It is clear that Harsha was a ruler who valued culture and scholarship, as he expressed interest in meeting Xuanzang. Apart from that, the king was also a patron of learned men. In addition to Banabhatta, another poet, Mayura was also living at his court. Moreover, Harsha is reputed to be the author of three Sanskrit works of literature – Nagananda, Ratnavali, and Priyadarsika. Some scholars, however, are of the opinion that it was actually Banabhatta who wrote these works. In any case, Xuanzang eventually visited Harsha’s palace and a close personal friendship between the two men was formed.

Xuanzang’s Great Tang Records on the Western Regions contains a description of Harsha by the monk. According to Xuanzang, the king had been a Hindu during the earliest part of his reign, but converted to Mahayana Buddhism later on in his life. The king’s devotion to Buddhism may be seen, for instance, in the grand Buddhist convocation at Kannauj that he organized in 643 AD. Xuanzang wrote that the massive convocation was attended by hundreds of pilgrims and twenty kings.

Additionally, a religious assembly called Moksha was held once every five years. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Xuanzang praises the king as benevolent and just ruler, whose kingdom prospered thanks to his energetic administration. The monk’s portrayal of Harsha as a model ruler ought to be taken with a pinch of salt, considering that he was writing about a fellow Buddhist. In any case, it was largely thanks to Harsha’s patronage that Xuanzang was able to journey back to China in 643 AD.

The End of Harsha’s Rule

Two years before Xuanzang embarked on his journey home, Harsha sent an envoy to the Tang court, thereby establishing the first diplomatic relations between India and China. Emperor Taizong responded by sending a Chinese envoy, Wang Xuance, to India in 648 AD. Unfortunately for Xuance, Harsha had died in 647 AD, before the diplomatic mission even left China. Xuance and his party, however, only learned about the king’s death after arriving in India. Harsha’s death caused turmoil in northern India. As he died without leaving an heir, the Vardhana Dynasty came to an end, and the throne was usurped by Arunasva. The new king was hostile towards the Chinese, attacking Xuance and the diplomatic mission.

Fortunately for the envoy, he managed to escape, making his way to Tibet. Some records state that Xuance assembled an army from amongst the Nepalese and Tibetans, launching an attack on India. Thousands of captives were taken, including Arunasva. The defeated king was brought back to China and spent the rest of his life as an attendant of the Chinese emperor. Xuance’s war against Arunasva is an incredible tale. Since the story was only written several centuries after it was alleged to have taken place, its veracity is rather questionable.

To conclude, Harsha is portrayed by the available sources as an extraordinary king whose reign brought great prosperity to northern India. These sources, however, should be read with caution, due to the possible biases in them. Banabhatta for example was a court poet of Harsha, whilst Xuanzang was a close friend and co-religionist of the king. In spite of all that Harsha had achieved during his lifetime, he failed to ensure the survival of his dynasty. As he died without an heir, his throne was usurped and the Vardhana Dynasty came to an untimely end. Moreover, turmoil ensued in northern India following the king’s death. The short-lived Vardhana Dynasty didn’t have the chance to create a lasting impact on Indian history and was soon forgotten.

Top image: Harsha Source: abir / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 3rd, 2021

February 3rd, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: