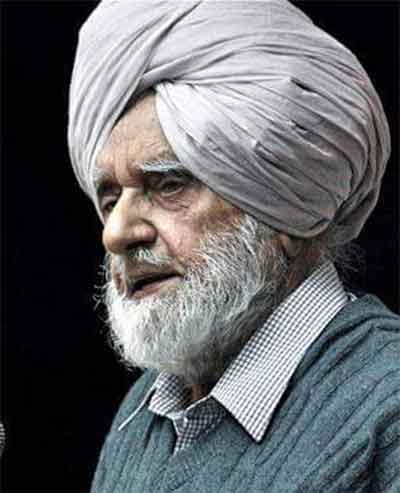

Prof Randhir Singh was a Marxist scholar, political theorist and teacher from India. He was one of the founders of the student movement in India in the 1930s and a freedom fighter who remained in jail during India’s freedom struggles in the 1940s. He was put in the same barrack in Lahore Central Jail where India’s foremost revolutionary Bhagat Singh was kept. He writes in his In Lieu Of A Bio-Data — “I was to spend a few months, among the happiest in my life, in the ‘terrorist ward’ of this very prison with some of the surviving comrades of Bhagat Singh. It is time to remember his legacy. More importantly, not to forget it. It is with huge respect and responsibility towards him, I write this piece today.

Politics is not reserved for the dominant echelons of society. But, it determines the baseline of structural changes and also challenges the hitherto existing system and the rot within and outside. Not only it shakes the economic understanding of an individual or a group, or that of the state apparatuses, it also updates the parties involved in tricks of the trade. It is impossible to remain indifferent to the political surroundings. Politics is a conscious process built on the ideologies of the political formations — that goes right to left. We have been blessed to witness one of the greatest intellectuals of our times — Prof. Randhir Singh. From the day he took his first breath (09 January 1921) until he lived his last (31 January 2016), he dedicated his mental, physical strength to political thoughts and its renditions. He was a living embodiment of political science.

In his 1967 book, Reason, Revolution and Political Theory, he tackled the complex question of functioning culture, history and economics from a Marxist point of view, dealing with aspects affecting politics in the form of traditions and heritage. As the society moves forward, newer contradictions walk with it giving birth to economic and political changes. These changes, then, might include the questions of religion, caste, language, etc. in the larger political outlook. His other book Of Marxism and Indian Politics published in 1990, examines the features and characteristics of India’s model of progress. Through understanding class, the book sweeps all debates in the country’s hyped ‘development’ as it digs the question of why religious fanaticism is on the rise. The book places it in the unequal uneven distribution of resources and productions’ mode. Prof Randhir Singh brings in very lively examples to convey the complexities of theoretical realities. He says that the 1947 transfer of power to India by the British did not bring any structural change. He wittingly says that the ailments of the past were added to future diseases that came with the emergence of capitalism in the country.

In his 2008 Marxism, Socialism, Indian Politics: A View From The Left, he analysed different interpretations of Karl Marx in India, and said that socio-economic and political aspects were lifted and applied from the Soviet Union. India as a country was not read from within, through the Marxian lens as a tool, but as a dogma copied from other nations. This is the major reason that the communist parties were unable to give a concrete program based on Marxism for the radical social transformation in India.

In his 2006 The Crisis of Socialism: Notes in Defence of a Commitment, Prof Randhir Singh criticises the argument that fall of the USSR was the end of Marxism. In his Of Marxism of Karl Marx, he goes on to say: “the collapse of ‘Soviet Socialism’ needs to be understood as one historically specific outcome of Marxism…and not as signalling some final demise of Marxism itself.” Any one particular outcome in history, such as the fall of the USSR, lacks the energy to settle the questions of capitalism and socialism once and for all. Until capitalism exists, the questions of alternative political realities will remain alive.

In his 2009 book, Indian Politics Today — An Argument for Socialism Oriented Path of Development, he argues that the open market approach adopted by the Indian state under the diktats of the ruling class, in 1991, the people of India had to face one tragedy after the other. In his On Nationalism and Communalism in India, 2010, he says that as and when these tragedies and crises explode, the ruling class have no option but to take shelter in the revival of the fundamentals of communalism masquerading as promoting nationalism.

In his 2009 Contemporary Ecological Crisis — A Marxist View he argues that capitalism is directly in war with nature. Marx says — “Capitalism tends to destroy its two sources of wealth: nature and human beings.” Prof Randhir Singh puts it in his own style. He writes — “Environmental degradation is the natural, a necessary result of capitalism.”

Professor Randhir Singh is no more with us. He died on this day in 2016. But his spectacular, insightful writings are always there with us. He was always thoughtful. He would always try to see things in alternatives, in the dialectics of things. He always worked for social transformation. He lived for people. He died for people. I remember what a Marxian scholar Bertell Ollman said about Prof Randhir Singh — “If I wasn’t already over 50, I would probably say something like: When I grow up I want to be a professor like Randhir Singh.” I am also over 50. I have taught all my life. But I second Bertell Ollman’s dream. If I had a chance, I would also say something like: When I grow up I want to be a professor like Randhir Singh.

Dr Kuldip Singh has been a faculty member in the Department of Education in Punjabi University, Patiala. Kuldip has worked extensively in the field of learning and unlearning. He has been an activist and a thinker. His upcoming book on the letters of Professor Randhir Singh, one of the leading Marxist intellectuals in India, will be out soon.

Related posts:

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

January 30th, 2022

January 30th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: