The end of the 3,000-year-long Bronze Age was one of the most violent periods in history. Hittites and Egypt are usually cited as the last remaining major powers until a recently translated stone frieze, written around 1180 BC, describes another political and military power forgotten and overshadowed by the empire they destroyed.

Georges Perrot and the Great-King’s Limestone Frieze

French archaeologist Georges Perrot watched villagers in western Turkey unearth a huge 3,200-year-old limestone frieze in 1878, measuring 95 feet (29 m) long and 13.8 inches (35 cm) tall. He couldn’t read the hieroglyphics and copied the engraving before it was repurposed as part of the foundation of a new mosque. Professor Perrot’s copy of the ancient frieze remained in a private collection until sold and translated by a team of Dutch archaeologists in 2017.

Early inhabitants of Anatolia were largely Indo-Europeans, first Luwians then Hittites. Luwians were divided into small kingdoms constantly quarreling among themselves, and Hittites took advantage of their disorder to establish an empire covering most of Anatolia.

The enormous stone panel copied by Perrot was originally commissioned by Great-King Kupanta-Kurunta. It describes history’s first-known international multi-ethnic coalition. It memorialized his role in defeating the Hittites and subsequent control of Mira and Arzawa, powerful monarchies in western Anatolia, along with five smaller kingdoms, including the city of Troy / Ilium.

It’s unlikely we’ll know who assembled the alliance between Luwians, Phrygians, Kaskians and Sea People, or the command structure involving multiple kings and alliances. Great-Kings Muksus, Kulanamuwas, Tuwatas and Piyakuruntas are mentioned most often.

The 3,200-year-old Luwian hieroglyphic inscription by the Great King of Mira, Kupanta-Kurunta, tells the story of Rameses III and the end of the Bronze Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. ( Luwian Studies )

The Enigmatic Sea People

By 1190 BC the Hittite Empire was wracked by famine, social unrest and dispute over royal succession. When viewed from a Luwian perspective, the time was ripe to destroy the Hittites. Kupanta-Kurunta III may have led the initial invasion when the Hittite army was in the north, perhaps prearranged with Kaskians.

According to the frieze, the apparent lack of Hittite soldiers gave Kupanta-Kurunta the “right” to march in and take over. The Hittite response must have been inadequate because other Luwian forces invaded western Hatti, while Kaskians, from the Pontic Mountains, attacked the capital of Hattusa.

While rebel forces destroyed inland towns, Luwian coastal kingdoms amassed a fleet of ships to disrupt trade. Egyptians referred to them as “people from the sea,” and it was French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero who popularized the phrase “ Sea People ” in 1812.

Were the enigmatic Sea People vicious nihilists bent on the destruction of civilization, as portrayed by Egyptians? Historians often use Sea People as a pejorative term, a default-setting, for who to blame for most violence at the end of the Bronze Age . But, where did they come from?

History’s First Maritime Blockade? Understanding the Role of Troy

The Sherden were Akkadians who worked both sides of the fence, serving as bodyguards of Ramses II the Great, and then fighting against his son, Merneptah, and later Ramses III . The Lukka, Akwash, Shekelesh and Kariska were from the western part of Anatolia. Meshwesh and Libu were Libyans while the origins of the Teresh and Denyens are lost to history. Tjsekkers, Ekwesh and Weshesh may have been Aegeans, and the best-known were Pelesets, probably from Crete.

What appears as piracy and wanton violence may have been history’s first maritime blockade, intended to destroy the Hittite economy. Any collateral damage to Egyptian and Mycenean property was a bonus because they were next.

Troy’s location at the Dardanelle Straights, or Hellespont, a narrow waterway connecting the Aegean Sea with the Sea of Marmara and Black Sea, made it one of the most important cities in the ancient world. Early vessels could not sail into the wind, so the almost-continuous northerly winds, accompanied by a strong southerly current made the Dardanelles unnavigable without knowledgeable local pilots.

This also made Troy a “forced port of call” until winds eased up or changed direction. That wasn’t a problem for Mycenean-Greeks who were valuable trading partners with the Hittites. However, that friendship made them enemies of Luwian rebels who frequently pirated Greek ships.

Who were the Trojans and what role did they play in regional politics? Homer gave them Greek names and described the multi-ethnic Luwian-coalition several times. In the Iliad, Book 2, Line 804, Iris appeared in the guise of Polites and describes this coalition of “scattered foreigners” to Hector. “Their speech and dialects were all different, as they spoke a mixture of languages—the troops hailed from many parts.”

The trouble between Greeks and Luwians began shortly after the Hittite Empire was carved up among the victors and Kupanta-Kurunta III took over the city of Troy. That gave Luwians control over access to Black Sea trade and dramatically changed the regional balance of power. Restrictions on Mycenean merchants would have been unacceptable to Greek societies whose prosperity depended on international trade. The only way to break the Luwian death grip on the Greek economy was to eliminate Troy.

The Procession of the Trojan Horse in Troy by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo. ( Public domain )

How Does the Trojan War Fit in?

The Trojan War was a maximum effort for Mycenaeans but not the far more numerous Luwians. Unfortunately for the Greeks, Agamemnon was obsessed with capturing the wealth of Troy and nearly all Mycenaean royalty, nobles and finest warriors were far away, leaving little protection back home.

That’s when Sea People attacked the Greek mainland, destroying Athens, Thebes, Tiryns, Midea, and Pylos. Athenians survived a Sea People assault by retreating to the fortified hilltop-Acropolis but couldn’t save the city and port from being burned.

The subsequent treaty to release those besieged atop the Acropolis could be basis for the Minotaur fable. It was customary practice to hold children of high-ranking opponents as hostages to be educated in foreign courts. Mycenaean captives held on Crete could have described the huge multi-level palace at Knossos as a labyrinth.

The Trojan War signaled the height of Mycenaean power, until the coalition broke up and victors sailed home. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much left after Luwians laid waste to Greek cities and farms. Not all regents left behind wanted to give up power and several kings were murdered or exiled.

An unintended consequence of the Trojan War was the loss of boat-pilots able to navigate the treacherous Dardanelles, blocking Mediterranean merchant vessels from lucrative Black Sea trade. Mycenaeans won the defining battle but lost the war and faded into history.

Destroying the Hittites and Mycenaeans provided unimaginable wealth to Luwian victors but did not improve their situation. The lands they conquered suffered from the same drought and famine as Anatolia, but food was still plentiful in Egypt.

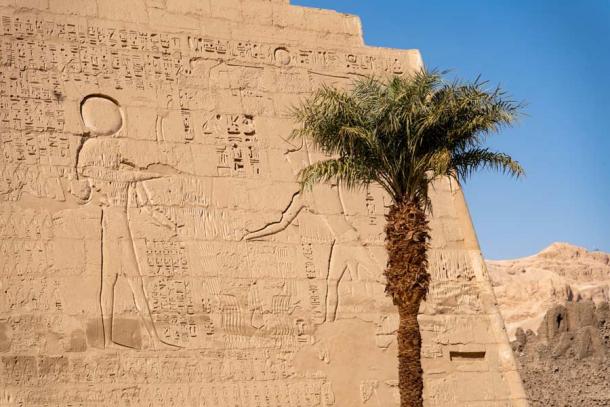

Exterior of the Mortuary Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu in Luxor, Egypt. Includes relief depicting the battles between Egyptians and the Sea Peoples, and their ultimate defeat. ( ronnybas / Adobe Stock)

Ramses III and Egyptian Naval Clash with the Sea Peoples

Wall images on Ramses III mortuary temple at Medinet Habu portray Luwian warriors wearing long tunics, but most wore kilts with knotted string-tassels hanging from the corners of the garment. Helmets were adorned with animal horns, feathers and clan totems indicating different tribal or ethnic groups.

Invaders may have been better armed than their opponents, benefiting from weapons introduced by migrants fleeing ice and cold of northern Europe and steppes. Weapons like the Nau Type II cut-and-thrust sword, javelin and round shield revolutionized hand-to-hand combat.

The only way Luwians could defeat Ramses was to split Egyptian forces and attack separate locations simultaneously. Sea People swept down the coast looting and stealing whatever they wanted and at the same time the Luwian army moved south through the Beqaa Valley, east of Phoenicia.

Provisions were readily available in coastal towns and there was no need for long-term planning. It wasn’t as easy for the land-army, depicted on tomb walls as motley caravans with flocks of animals walking beside wagons piled high with plundered treasure. What they didn’t have was food.

The logistics of supplying an army with adequate provisions had always been difficult in the Middle East and semi-arid Mediterranean. However, this cross-country trek occurred during a severe multi-generational drought when there was little food. Invaders were forced to live off the land, consuming everything in their path like a Biblical plague of locusts.

The need to continually stop and pillage in search of food significantly delayed the Luwian southern migration. Egyptian scouts tracked the invaders until they stopped at the headwaters of the Jordan River to rest and loot the Amorite kingdom of Amurru, a former Hittite vassal, in northern Lebanon.

Relief from the mortuary temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu which shoes the Sea People in their ships in battle with the Egyptians. ( Public domain )

Ramses III and His Defense of Egypt Against Invaders

However, Ramses III conducted a preemptive strike to prevent Luwian forces from linking up. The Battle of Djahy began shortly after dawn when Egyptians surprised Luwians dispersed in search of food and survivors “fled to the four winds.”

The army raced back to Egypt, arriving just in time to meet the second Luwian attack at the Battle of the Delta . Thousands of archers hid among the reeds along both banks of the Pelusium Canal and overwhelmed the Sea People under volleys of arrows. Egyptian soldiers in boats and on shore used ropes and grappling hooks to overturn vessels or reel them in like fish.

When it was over Ramses III declared:

“The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Khatte, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on, being cut off at (one time). A camp [was set up] in one place in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land like that which never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared for them.”

The Battle of the Delta wasn’t the final crises facing Egypt. Things got worse after the Luwian confederation broke up into ethnic and tribal groups, and Sea People known as Peleset moved into Canaan.

Ramses III crushed the Luwian coalition in two great battles and defeated two separate Libyan invasions, but drought and persistent food shortages made life unbearable for many Egyptians. Pirates shut down vital sea trade and the loss of Canaan cut off land routes to Assyria and Babylonia.

There was little private enterprise to tax while temples hoarded land, gold and silver the pharaoh needed but couldn’t tax. Shortages of raw material caused economic chaos and lack of copper and tin to make bronze weapons was a national defense crisis. Egypt never recovered from the loss of Canaan.

When craftsmen and painters working on the funerary temple of Ramses III were not paid, angry workmen held history’s first-known labor strike. However, the mayor and local officials were unable to meet their demands and strikers returned the next day, with their wives, and sat down in the partially-completed temple until paid.

Head of mummy of pharaoh Ramses III, who was murdered during the Harem Conspiracy. ( Public domain )

Ramses III and the Harem Conspiracy

Although considered a “great” pharaoh by many, Ramses III was murdered by someone he trusted. The warrior-king died in the failed Harem Conspiracy (1155 BC) led by his second wife, Queen Tiye, who wanted to place her son, Pentawere, on the throne.

Ramses was enjoying a private moment with his harem when ruthlessly attacked by at least two assailants. It was only after his mummy was examined in recent years using modern CSI technology the extent of the Harem Conspiracy was revealed. His body shows defensive cuts on his palms and bottoms of both feet, and the left big toe was chopped off.

While the king defended himself from attacker(s) at his front, someone snuck up from behind and slit his throat. The assassination of Ramses III signaled the end of Egyptian power, when he was succeeded by a series of pharaohs named Ramses with few successes to their credit.

The list of people put to death for involvement in the Harem Conspiracy included a queen, royal prince, physicians, high-ranking court officials, army officers and low-ranking palace employees. Among those executed were wives of harem guards who might have heard something but didn’t report it.

When archaeologists discovered a bizarre looking male corpse with a contorted face they dubbed it the “ screaming mummy .” Egyptologists led by former Antiquities Minister, Dr. Zahi Hawass, used DNA to confirm the body was Pentawere, executed for conspiring to murder his father, Ramses III.

The cadaver was not embalmed but left to dry in natron and resin poured into its mouth. Instead of proper burial linen, Pentawere was wrapped in uncured sheepskin, a sign of impurity. Just to make sure he never went to heaven, there was no sarcophagus or name to identify the assassin, dooming him to wander the tomb for eternity.

This article is an edited excerpt from Doug Mears’ latest book, Did Global Warming End the Bronze Age? The History of Climate and Natural Disasters available from Amazon.

Top image: Depiction of the Sea People during naval battle with Egyptians as depicted on the temple of Ramses III in Medinet Abu, Egypt. Source: AlternatHistory

By Doug Mears

References

Barjamovic, G; Chaney, T; Cosar, K. Oct 2017. Trade Merchants and Lost Cities of the Bronze Age .

Chadwick, J. 1976. The Mycenean World . Cambridge Univ Press, NY NY, USA.

Cline, E. 2014. 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed . Princeton Univ Press, USA.

Drews, R. 1993. The End of the Bronze Age . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton Univ Press.

Guiot, J. and Van Campo, E. May 2015. Drought and Societal Collapse 3,200 years ago in the Eastern Mediterranean .

Redford, S. 2008. The Harem Conspiracy: The Murder of Ramses III . Northern Illinois Univ Press, DeKalb, Ill, USA.

Robbins, M. 2001. Collapse of the Bronze Age . Authors Choice Press: Lincoln, NB.

Robbins, M. 2017. Looking for Homer: Finding the Trojan War . iUniverse Press, Ind, USA.

Warry, J. 1993. Warfare in the Ancient World . Salamander Books Ltd London.

Related posts:

Views: 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 25th, 2021

December 25th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: