Israeli law requires that any object discovered in the country which is of historical interest, or was created before 1700, becomes the property of the State. It must be reported to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) within 15 days. And if it is found on a construction site, work is to be halted immediately after discovery for the next two weeks.

So when an unusually ornate Roman-era sarcophagus was uncovered in 2015 during construction of an Ashkelon neighborhood, the contractor should have let the authorities know. Instead, he made sure the sarcophagus stayed out of sight. Otherwise he would have had to halt construction, and perhaps to delay work indefinitely if the IAA decided to begin excavations at the site.

Unfortunately for him, archeologists from IAA’s Theft Prevention Unit making a late-night raid found the hidden sarcophagus. Today it is on display at one of the Authority’s 320 unique open-air archaeological gardens and exhibits. Found all over the country, they are located in well-designed sites that are free to all comers and, with one exception, accessible 24/7.

Head of the Department of Museums and Displays at the IAA is Dr. Orit Shamir, responsible for all of our archeological gardens and exhibits. What makes them particularly exciting is the wide variety of settings, made possible because each was designed by a different set of curators and architects.

A Roman-era sarcophagus discovered during construction in 2015. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

A few weeks ago, and despite the black coronavirus mood in the country, we decided to explore four archaeological gardens and to view one archaeological exhibit. None of them require climbing steps, and all of them took us out into open air.

To our surprise, we found that despite easy access to the sites, there was no evidence of vandalism. These days young people from all sectors of society are exposed to archaeological exhibits and gardens, and participate in excavations — vital tools that teach the value of protecting our artifacts.

Most of Israel’s ancient settlers were farmers who grew grapes, cereals, and olives from which they produced wine, grains and olive oil.

Archaeological gardens help us understand what their daily lives were all about by providing a look at the tools of their trade, architectural elements, water sources and, in Ashkelon, the stone anchors that kept their boats moored in the harbor. Because most of the artifacts on display were discovered in or near the gardens themselves, they often have similar themes but are actually quite diverse.

Ancient columns on display in Ashkelon’s archaeological garden, which is situated near the Mediterranean Sea. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

Ashkelon

Curator Ayelet Grover had a clear vision in mind when she created the garden in Ashkelon. It was her plan to bring the past into the present with artifacts discovered throughout the city and dating back several millennia. On display in the garden are splendid column capitals, bases and a pedestal made of imported marble, an ancient gutter found during construction at Barzilai Hospital, stone anchors, several sarcophagi – including the exquisite specimen that was unearthed and hidden for a time — and a Roman-era mosaic.

What is most impressive about this garden, besides the rich archaeological items on exhibit, is its setting. Ashkelon’s Archaeological Garden is next to an unusually elaborate playground and located only meters from the Mediterranean Sea, which delights with its look, the sound of the waves, and delightful sea air.

An olive crusher at the Hod Hasharon archaeological garden, the oldest known artifact of its kind. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

Hod Hasharon

Grover also designed the archaeological garden in Hod Hasharon, a quiet town south of the city of Ra’anana in central Israel. The centerpiece of a charming little park with benches, trees, plants and flowers, the garden displays antiquities from farmers’ daily life long ago like an ancient well capstone, the oldest known type of olive crusher (saflul), and the earliest known system for pressing oil (bodida).

Hod Hasharon is home to a fabulous ecological park with something for everyone. Located right in the middle of the city, it is perfectly maintained and features trails, a catfish-filled stream, a lake, a bridge, exercise equipment, overlooks, and lots and lots of grass.

Some experts believe Givat Titora is the ancient site of Modi’in, home of the fabled Maccabees. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

Givat Titora

Thousands of years ago, a deserted hill in the center of Israel bustled with activity. Called, today, Givat Titora, some experts believe it to be ancient Modi’in, home to the Maccabees who vanquished the Greeks and returned the Land of Israel to Jewish control. Others have identified it as the biblical Gitaim (“two wine presses”), mentioned by Nehemiah (11:33).

Among remains on the hill are overgrown caves and cisterns, a trough, a Jewish ritual bath (mikveh) and ruins of a two-story Crusader fortress called Tantara that utilized Jewish gravestones from the Second Temple Period in its foundations.

Transformation of the hill in 2018 into an archaeological garden was carried out by curator Edna Ayash. Here, ancient remains mingle with the natural beautify of the hill (gorgeous in autumn, winter and spring) and well-preserved or restored artifacts that include a wine press, decorative capitals, the stone lintel from a farmhouse, and a screw press that probably dates back to the fourth and fifth centuries.

Winding trails run all through the garden, and a beautiful overlook offers a stunning view of the region (probably the reason the Crusaders chose this site for their fortress). An audio guide in English and Hebrew tells the story of a battle that took place nearby during the 1948 War of Independence. Best seasons to visit: autumn, winter and spring when masses of flowers bloom everywhere.

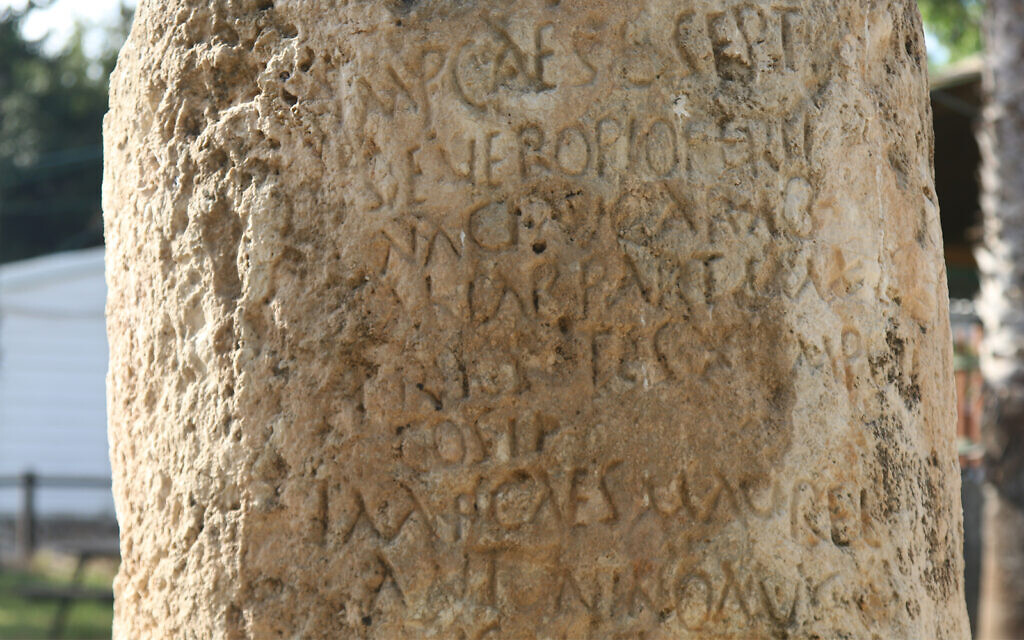

Inscriptions on a Roman-era milestone at the Givat Yeshayahu archaeological garden. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

Givat Yeshayahu

Situated next to moshav Givat Yeshayahu and adjacent to offices of the Jewish National Fund, the archaeological garden sits, naturally, in a lovely forest setting. Designed by curator Hagit Neugeborn, it features an ancient farmers’ roller (maagal), the heavy door to a mausoleum, a rolling stone, donkey mill, ossuary, and an elaborate oil press. Heavy Roman era milestones, two of them inscribed, were brought to the site after cranes extracted them from their location along today’s Highway 38.

Extra added attraction at Givat Yeshayahu: a platform with picnic tables surrounded by palm trees.

The base of a column on display in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter archaeological exhibit. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

Jerusalem archaeological exhibit

After the 1967 Six Day War, the ravaged Jewish Quarter of the Old City underwent a long process of reconstruction. All kinds of architectural elements were discovered in the rubble, while others had been incorporated into later structures. On view in a lovely archaeological exhibit, they point to the existence of wealthy residents living the good life, whose private and public buildings were luxurious in the extreme.

Curator Ravit Nenner-Soriano inaugurated the archaeological exhibit a couple of months ago — despite the coronavirus — with a wonderful collection of artifacts. An elbow column on display was used to support roofing vaults during the Crusader era; an ornamental item from the Middle Ages and called a muqarnas connected round and square elements in a construction. Other antiquities include a beautiful frieze, a decorative cornice, and bases and capitals made of marble.

While the archaeological gardens we explored were signposted in Hebrew only, the attractive archaeology exhibit in the Quarter features detailed signs in English, Hebrew and Arabic. Visitors can take the opportunity to walk through the Quarter, full of historic sites like the Roman Cardo and the Broad Wall, built by King Hezekiah in the 8th century BCE.

The Mediterranean Sea, seen from Ashkelon’s archaeological garden. (Shmuel Bar-Am)

—

If you need directions to the various gardens, feel free to contact us at [email protected].

* The archeological garden next to Moshav Givat Yeshayahu is closed to the public on Saturdays.

Aviva Bar-Am is the author of seven English-language guides to Israel. Shmuel Bar-Am is a licensed tour guide who provides private, customized tours in Israel for individuals, families and small groups.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 20th, 2020

September 20th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: