On December 24, 1950, the words of Pope Pius XII resounded throughout the world in his Christmas radio message when he said: “(…) The tomb of the Prince of the Apostles has been found! ” The Prince of the Apostles is none other than Peter, who was given the keys to the Church by Jesus himself. And on this day, the Christian faithful around the world learned that the Peter’s tomb had been found. But the truth behind this story is much more complicated and even today, 70 years later, there is considerable controversy regarding the claims about Peter’s tomb and lots of questions too.

The Pope’s grand statement in his radio address was the climax of a series of complex, mysterious events, studded with procedural errors and disagreements among scholars. And the problems got so bad that the Vatican silenced the entire investigation and prevented anyone from digging deeper.

But over the years more facts and theories have emerged that shed new light on this story, turning it into an archaeological mystery that likely has answers that are quite different from what the Pope claimed in 1950.

Eugenio Pacelli Pope Pius XII started the official research into Peter’s tomb. (Michael Pitcairn / Public Domain )

The Vatican Cave Excavations Under Pius XII Reveal Secrets

At the death of Pope Pius XI, Eugenio Pacelli succeeded him on March 2, 1939 AD under the name of Pius XII, thus underlining the continuity with the work of a pontiff to whom he was bound by esteem and affection. Precisely for this reason Pacelli wanted to fulfill the wish of his predecessor: to be buried in the sacred Vatican Grottoes (Grotte Vaticane) near the tomb of Pius X and the tomb “traditionally” attributed to Saint Peter. This underground tomb area is in the crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica, which is located exactly below the great dome of the magnificent Italian structure.

St. Peter’s Baldachin in the nave of St. Peter’s Basilica. The Baldachin is a large Baroque sculpted canopy, by Bernini, positioned over the high altar. ( Stripped Pixel / Adobe Stock)

During WWII, work officially began under the Altar of Confession and Bernini’s Baldachin. There had already been other excavations in 1925 and 1939 but they had ended early. The third excavation process was well timed and hopefully would confirm the traditional belief that Peter’s tomb was located in the crypt under the heart of Vatican City.

To avoid structural problems, the Vatican researchers decided to dig a tunnel under the altar leading to the area of interest in the crypt. This was the beginning of a series of poorly coordinated and badly completed tasks. Each person involved did a little on their own, without the use of an excavation log, and the debris was simply piled up in boxes and taken away.

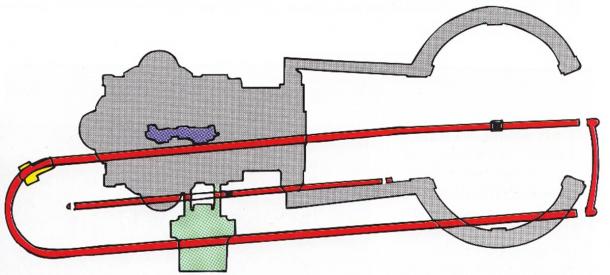

On January 18, 1941, the excavations reached a brick wall that was identified as part of Nero’s Circus in which, according to tradition, Peter was martyred and crucified upside down between 64 and 67 AD.

Layout of the Vatican necropolis (green area) and it’s overlap with Nero’s Circus (shown in red) with the outline of the basilica shown in grey. The Altar of Confession, and the crypt area below it, is shown in purple. (Mogadir / CC BY 3.0 )

The excavation campaign continued despite the bombs dropped by the Allies (the Vatican was hit by at least 5 bombs during WWII). However, this did not stop the work, which continued until 1949. Participants included: Monsignor Ludwig Kaas, Bursar and Administrator of the Reverenda Fabbrica di San Pietro; Bruno Maria Apolloni Ghetti, the architect in charge of the surveys; Enrico Josi, inspector of the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology; the Jesuit Father Kirschbaum, professor of archaeology at the Gregorian University; and Antonio Ferrua, a leading member of the Society of Jesus, professor at the Pontifical Institute of Christian Archaeology, and writer and columnist of the magazine La Civiltà Cattolica .

The results of the excavation work were presented to the Pope in a report entitled Esplorazioni sotto la Confessione di San Pietro in Vaticano eseguite negli anni 1940-1949 . According to this report the excavations below the Altar of Confession led to the discovery of a vast pagan necropolis that was called “P,” in which various burial tombs were found.

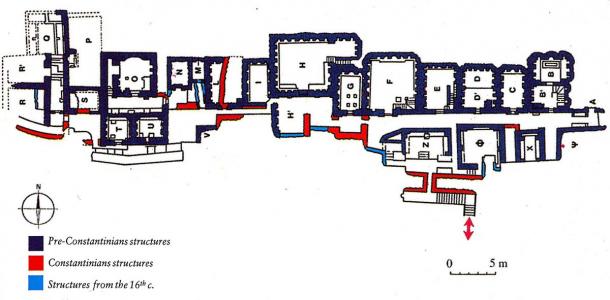

Mausoleums in the Vatican necropolis with temporal classification of the buildings, with the P area shown in the upper left. (Mogadir / CC BY 3.0 )

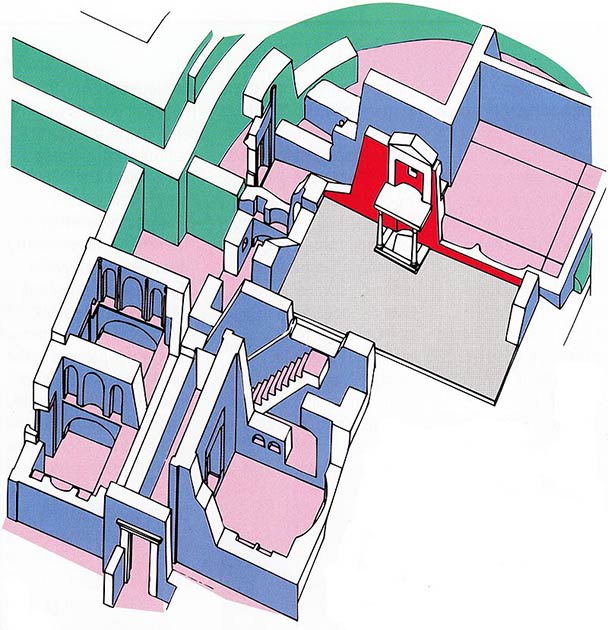

According to some historical sources, Emperor Constantine moved what were supposedly Peter’s bones from one of the tombs on the ground level to a burial aedicula (small burial shrine) nearby. This tiny structure was soon recognized by the archaeologists as the so-called “Trophy of Gaius.”

The Burial Aedicula Shrine And It’s Odd Exceptions

The burial aedicula found by the Vatican archaeologists was in poor condition, placed against a wall covered with red plaster, in which a niche had been dug. In the niche were two small columns holding a slab of travertine (sedimentary stone) on which no Christian symbol was visible. This is a very unusual for a shrine that was believed to have been built by followers of Jesus who traditionally used to leave images, frescoes, or graffiti related to their faith on what they viewed to be “holy” remains.

The next step was the attribution of this aedicula to the so-called Trophy of Gaius, which, in the enthusiastic statements of some specialists, was a logical confirmation of an oral tradition reported by Eusebius of Caesarea (265-340 AD) in the work Historia Ecclesiastica . This attribution constitutes one of the weakest links in the entire chain of data and findings and was met by total disagreement from “outside” archaeologists.

The Trophy of Gaius

What is the “Trophy of Gaius”? Eusebius reports a story that he heard from his teacher in Caesarea who in turn had learned it from Origen of Alexandria. In this story, the Christian Gaius, during the time of Pope Zephyrinus (199-217 AD), had a disagreement with a certain Proclus, a follower of Montanism, a sect detached from Christianity that followed the teachings of Montanus and his revelations.

Eusebius reports the words of Gaius to Proclus in Historia Ecclesiastica 2,25,5: “I can show you the trophies of the Apostles. If you want to go to the Vatican Hill or the Ostian Way, you will find the trophies of these two (Peter and Paul), who founded this Church.”

A reconstruction of the area around the “tomb” of the apostle Peter in St. Peter’s Basilica: The “Trophy of Gaius” and the Red Wall (red); Pre-Constantinian tombs (blue); Field P (grey); the apse of the old basilica (green). (Mogadir / CC BY 3.0 )

Eusebius does not provide any further explanation of these “trophies” (tropè, tropaion), which were simply commemorative artifacts related to a victory. This testimony is in essence a story heard years before by a teacher who had learned it from another teacher, without any other confirmation than mere hearsay. The consequence is that it cannot be accepted as historical testimony. Yet it was accepted as fact by some specialists and applied to the aedicula found in the crypt, which was in a pagan necropolis and on which there were no Christian symbols.

The attribution of the aedicula to the Trophy of Gaius appears today a simple inference, derived from the need of the high Catholic hierarchies to find the Peter’s tomb at any cost.

According to the Liber Pontificalis, which dates back at least to the fifth century AD, Constantine wanted to protect the aedicula and the bones with a double sarcophagus of silver and gilded bronze. It was 1.5 meters long (4.9 feet long) on each side, on which was placed a cross of solid gold donated by the emperor and his mother Helena. This double sarcophagus was built and positioned in the years 321-326 A.D.

Exactly above the aedicula, Constantine commissioned the construction of the Basilica Costantiniana, by levelling the ground and burying the tombs. The underground “tomb” was then protected by an outer wall, which was called Muro G (Wall G), because it was covered with graffiti.

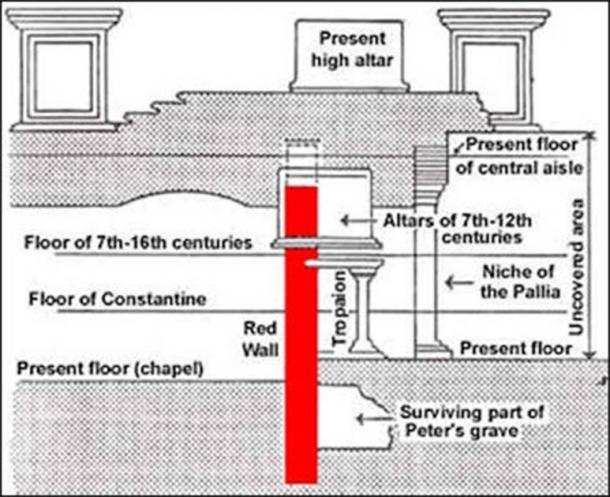

In time, various popes built their altars directly over the place attributed to Peter’s tomb in the central structure of the basilica. These include the altar of Gregory the Great (590-604 AD), which was incorporated from the altar of Callisto I (1123 AD), and the altar of Clement VIII (1594 AD).

But if that was the place where Constantine had buried the remains of Peter, where were the bones?

So Where Were The Bones Of St. Peter?

In 846 AD, the Saracens sacked the basilica, entered the crypt, and scattered the alleged bones of Peter on the ground, creating even more confusion in the process.

The Protestant specialist Oscar Cullmann, who also accepted the possibility that the aedicula might be the Trophy of Gaius, expressed himself as follows: “But what tomb has been found? There was no name, there were no bones.”

Cullman, of course, followed the founder of his church, Luther, who in Against the Roman Papacy, an Institution of the Devil (1544), expressed himself as follows: “. . .in Rome it is not known where the bodies of Saints Peter and Paul are, or even if they are there. The Pope and the cardinals know very well that they do not know.”

The location of the so-called tomb of Peter under St Peter’s Basilica ( Facts and Details )

Rough Excavation Work May Have Ruined The Whole Project

The WWII excavations, however, were carried out in a very lax manner unlike the skilled techniques and caution that one would expect from archaeological specialists. For example, the sanpietrini (excavator workers), in their hurry to reach their destination, violently broke through the altar of Callisto causing the ancient protective wall covered with red plaster (called the “Red Wall”) to collapse. The rubble collapsed into the next burial area, above the bones placed there by Constantine.

In the chaos, the bones were not seen immediately, but later they were noticed by Monsignor Kaas, whose pious nature required him to collect the bones, both of pagans and Christians, in a box, so that they could be buried later. These, however, had a different end: they were forgotten in the Vatican grottoes, where they remained for ten years. In reality, the bones in the crypt turned out to be animal and human. Immediately, one wonders why, if they really were Peter’s bones, they would have been mixed with the bones of others and animals as well.

The Archaeological Mystery Leads To A Bitter Feud

During the 1949 AD excavations, Antonio Ferrua stopped a worker who was carrying debris on a wheelbarrow. The worker had been hit by a piece of plaster on which there were inscriptions, and he decided to take the piece and bring it home. It remained in his possession for a long time until it was taken back to the Vatican. It was through Ferrua’s persistence that the plaster fragment was returned.

The second phase of the excavation operation continued from 1952 to 1957, and Pius XII entrusted the epigraphist (one who studies ancient inscriptions) Margherita Guarducci with the task of studying the graffiti on Wall G.

The piece of plaster the worker had taken home came into Guarducci’s hands and she found traces of red on it. And she discovered that it fit perfectly into a spot on the Red Wall. She concluded that it must have fallen from there. In addition to this, she found seven Greek letters on the plaster fragment: “Πετρ(ος) ενι.” Guarducci translated the inscription to mean: “Petros eni” or “Peter is here.” At this point, the epigraphist was convinced she had found the final proof that Peter was buried at this location.

However, the bones of Peter had not been found. Guarducci, invested with a huge responsibility, began to question all those who had taken part in the excavation. It was discovered that Monsignor Kaas, after excavation work ended for the day, had collected the bone fragments and put them in poorly catalogued containers inside the Grotte Vaticane. Margherita Guarducci was able to find one with a tag indicating the origin of the loculus of the Red Wall. It was lying on the ground, separated from the other boxes of materials. When Guarducci opened the box, she found red-painted plaster and minute samples of a reddish fabric, which also had gold threads in it.

The tests on the bones lasted ten years, until 1963 AD, and they confirmed that it was a single male individual, who had lived about two thousand years ago. It was almost a complete skeleton. The only thing missing were the bones of the feet, which confirmed the belief that Peter had been crucified upside down.

Moreover, some of the bone fragments showed traces of reddish coloration and therefore confirmed the contact with the red cloth for a very long time. Chemical examinations of the cloth determined that it was murex dyed and that the gold was authentic. Basically, the man’s bones had been wrapped in a purple royal fabric (the color of murex fades to red over time) containing gold threads. The petrographic examination of the soil confirmed that the findings came from the same area of the Red Wall.

The niche in the Vatican Grottos where the Plexiglass boxes of bone remains were placed (Dnalor 01 / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

A Dramatic Turn of Events: But Not 100% Convincing!

On June 28, 1968 AD, an official announcement was made by Paul VI to the world of the Catholic faithful. The bones were placed in nineteen sealed Plexiglass containers and placed where Constantine had buried them sixteen centuries earlier.

Among the specialists who worked on the project, Kirschbaum was, however, of an opinion contrary to that of the Pope and Guarducci. He was supported on several occasions by other experts who translated the phrase “Πετρ(ος) ενι” as “Peter is missing,” while others translated it as “Petronius,” identifying a rich Christian buried with due honors. Other experts even translated the inscription as “Peter is not here.”

The specialists did not even agree on the so-called mystical cryptography, which Guarducci believed she had discovered among the graffiti of Wall G. According to her, it was a secret writing with which Christians sent greetings of eternal life to their deceased. This was a technique used by pagans but had never been seen among Christians. Not surprisingly, the archaeologist’s arguments did not convince the other members of the team.

The Long Fight Between Gaurducci And Ferrua

The bone remains and their interpretation gave rise to a diatribe between the epigrapher Margherita Guarducci and archaeologist Antonio Ferrua, who vehemently opposed her hypothesis that the bones in the cloth belonged to Peter.

Ferrua was a renowned archaeologist who was highly respected not only in the Catholic sphere. In two articles published in the Jesuit magazine La Civiltà Cattolica (“La tomba di San Pietro”, La Civiltà Cattolica , March 3, 1990, pp. 460-7 and “Pietro in Vaticano”, La Civiltà Cattolica , March 17, 1984, pp. 573-81), he expressed himself in a rather critical manner and stated several times that he “could not publish” all the information in his possession, which would have destroyed the thesis of the discovery of Peter’s bones under the Altar of Confession.

Ferrua died in 2003 AD at the age of 103 and until his death he waged a personal and conscientious battle against the thesis of Margherita Guarducci. However, in the end, he was unsuccessful.

But shadows of doubt about the results of the archaeological investigations grew. In her memoirs, Guarducci reported that she had been betrayed and abandoned by the Vatican. She maintained her position regarding the excavations, until her death in 1997 AD.

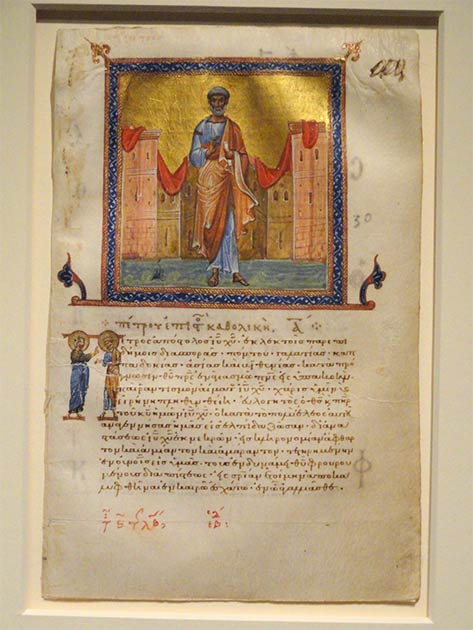

The Epistles of Saint Peter: a single page from a New Testament manuscript psalter from 1084 AD in Constantinople. (Daderot / CC0)

According To The New Testament: Peter Never Reached Rome

Strangely enough, the only historical source from which Peter’s story is taken, the Bible, was never examined, probably because it tells a completely different story. The Greek scriptures state that while Paul was sent as a missionary to the Gentiles and then to Rome, Peter was instead sent by the elders of Jerusalem to the eastern part of the known world, which included Samaria (Acts 8:14) and the area of Babylon.

In 1 Pet 5:13 Peter wrote: “She who is in Babylon, a chosen one like you like you, sends you her greetings, and so does Mark, my son.” Someone wanted to see in Babylon the city of Rome, to indicate that he was there. It is a statement without basis, because Peter was in fact really sent to Babylon, where there was a flourishing Jewish community.

Moreover, a geographical indication is included in the greetings, after clearly mentioning other geographical areas in the letter without any alternative secret reference. Among other things, a simple greeting does not require elaborate symbolism. Peter did indeed mean the city of Babylon, since that letter was sent to all “Jewish” people in the East, Asia Minor and even Babylon, as can be seen from 1 Pt 1:1.

In addition, around the year 56 AD, Paul sent written greetings to about thirty Christians in Rome but did not mention Peter once. Later, he wrote six more very important letters from Rome, even during Nero’s most fiery persecutions. And in these letters he does not mention Peter (2 Timothy 1:15-17; 4:11). However, in other letters he clearly refers to when the two met in cities like Antioch (Gal. 2:11-14). The historical account of acts mentions Paul’s arrival in Rome at the Appian market and the Three Taverns, where he met with his Christian brothers, but Peter was not there.

So according to the Greek Christian scriptures, Paul worked in Rome and Peter worked in the Middle East. This means that the bones buried in the Plexiglass boxes in the Vatican Grottoes are not those of Peter. But where are they then?

A final twist in this archaeological thriller occurred in 1953 in Jerusalem in the burial ground of Dominus Flevit. In this ancient burial ground archaeologists found an ossuary bearing the name of Peter in Aramaic script, translated as Shimon Bar Jonah, close to other ossuaries “labelled” with the names of characters found in the gospels.

In a future article, I intend to pursue this story further and, hopefully, finally solve the mystery of where the body of Saint Peter really lies . . .

Top image: Saint Peter receiving the keys of heaven from Jesus; but Peter’s tomb seems to be a mystery with a different message. Source: Renáta Sedmáková / Adobe Stock

SYNCHRONICITY – Flight 9941 by Pierluigi Tombetti

Events on the edge of reality. Passengers disappear, one after the other

Synchronicity, quantum physics and a thrilling plot:

beyond the mirror exists the answer to our questions…

———–

For author Jane Milton Keys, the most important moment of her career has come: the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in New York.

But the trip won’t be exactly what she thought. The passengers begin to disappear.

Unusual circumstances slowly begin to manifest themselves, shattering the certainties of logic, events that sink their roots into a very particular conception of existence, discovered by the Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung and the father of Quantum Physics, Wolfgang Pauli.

A great thriller based upon laws and scientific theories that open new extraordinary horizons to the human mind, offering intriguing answers to the most disturbing questions.

What is destiny? Do we really have freedom of choice? Is ours the only existing reality?

Can we solve situations with no way out?

A fascinating story, able to overturn normal points of view on what we are, and what we see.

From Quantum Entanglement to our consciousness, from Synchronicity to the collective unconscious, Synchronicity is the threshold of direct connection between the mind and the universe.

Booktrailer: https://youtu.be/Zv0WzVUiPBQ

Pierluigi Tombetti

A historian and author, Pierluigi Tombetti is considered one of the greatest scholars of National Socialism and the reasons for the Holocaust. He has been a consultant and guest on several television programs. Endowed with an inexhaustible creative vein, as an author he combines a passion for historical and scientific research with a love of thriller and adventurous fiction, in an unusual mix of intriguing stories always solidly based on documented facts and real events.

References

B. M. Apollonj Ghetti, A. Ferrua, E. Josi, E. Kirschbaum , Esplorazioni sotto la confessione di san Pietro in Vaticano eseguite negli anni 1940-1949 , Tip. Poliglotta Vaticana, 1951

P.B. Bagatti, J.T. Milik, Gli scavi del Dominus Flevit , Tipografia PP Francescani, Gerusalemme, 1958

A. Ferrua, B.M. Apollonj Ghetti, E. Kirschbaum et. al., Esplorazioni sotto la Confessione di San Pietro in Vaticano Eseguite negli anni 1940-1949 , Città del Vaticano, Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana, 1951

A. Ferrua, “La tomba di San Pietro”, in La Civiltà Cattolica , 3 march 1990, pp. 460-7; “Pietro in Vaticano”, in La Civiltà Cattolica , 17 march 1984, pp. 573-81

E. Kirschbaum, Die Gräber der Apostelfürsten , Frankfurt am Main, 1957

M. Guarducci, Le reliquie di Pietro sotto la Confessione della Basilica Vaticana , EAD, Città del Vaticano 1965.

M. Guarducci, Le reliquie di Pietro sotto la Confessione della Basilica Vaticana: una messa a punto , EAD, Roma 1967

M. Guarducci, Le reliquie di Pietro in Vaticano , IPZS, Roma 1995.

P. Tombetti, Il Settimo Sepolcro , Eremon Edizioni, Latina, 2009/2019

J. Toynbee, John Ward Perkins, The Shrine of St. Peter and the Vatican Excavations, London, Longmans, Green, 1956

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 12th, 2020

November 12th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: